Like lol, jk, and even XD; Japanese people have their own version of internet slang and texting lingo — also known as ネットスラング (netto surangu). Have you ever tried using social media, like Facebook, YouTube, or Twitter, in Japanese? Scoured across comments sections, posts, and message boards are letters and symbols being used in ways you’ve never encountered before. You may recognize the English letters, but they don’t make a lick of sense to you. So you may be thinking, what on earth does everything mean?

You have just been exposed to Japanese internet slang, and just like English internet slang, it looks more like secret codes rather than language you would learn in the classroom. While they are widely used to communicate online, Japanese internet slang terms are often not officially recognized in the Japanese language, nor are they found in Japanese textbooks.

However, despite this, in order to use the most common social media platforms or text your friends, Japanese internet slang is essential to know. So, let’s learn some of the most common internet slang you will come across so you can navigate the internet in Japanese and actually understand what people are saying!

Basics of Japanese Internet Slang

スラング (surangu) is a loanword from English that means “slang” and ネット (netto) is just “net” from “internet”. As with any language, you’ll come across numerous words, expressions, and abbreviations that are exclusively used on the internet or in text messages. Japanese internet slang terms can be challenging to understand because they don’t follow the same rules as standard Japanese.

Unlike the regular Japanese writing systems, Japanese internet and texting slang use romaji (ローマ字), or the roman alphabet, much more frequently. They are often shorter and more casual, incorporating English words and expressions. Additionally, they can change rapidly over time, making it essential to stay up-to-date with the latest trends.

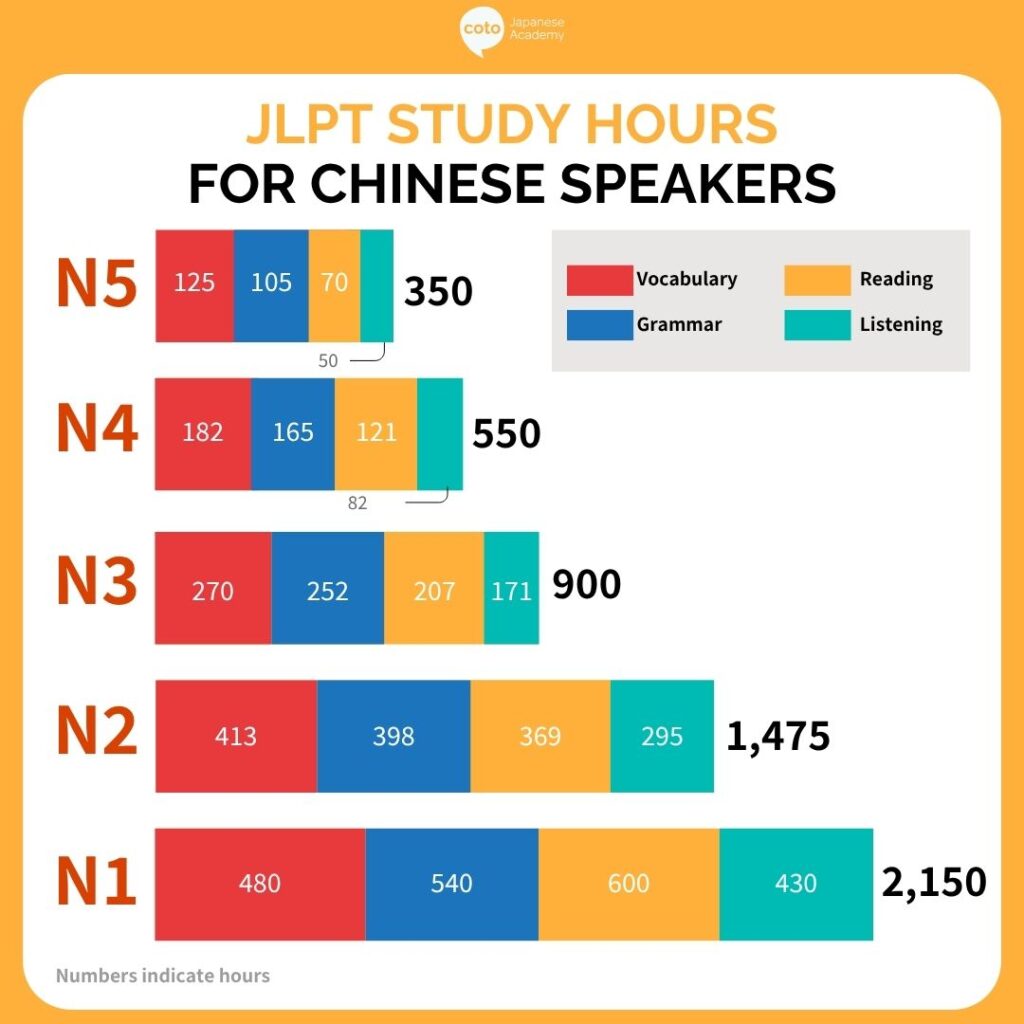

If you want to learn more practical Japanese, one of the best ways to understand this slang and lingo is by practicing with native speakers. Schools like Coto Academy focus on conversational Japanese and can help you build confidence through real-life practice.

Why Japanese Slang is Difficult to Understand

Japanese slang often employs wordplay, abbreviations, acronyms, and puns that may be difficult to decipher without some understanding of Japanese culture and context. For example, a typical Japanese slang term “JK” refers to “joshi kousei,” which means high school girl, but the abbreviation itself doesn’t necessarily indicate its meaning to non-native speakers.

Take a look at an example to demonstrate how Japanese internet slang might not make sense despite its use of English letters:

どこかから DQN が 現れて わりこんでいったよ!ムカつく!

Doko ka kara DQN ga arawarete warikonde itta yo! Mukatsuku!

A DQN appeared out of nowhere and cut in line! So annoying!

You might have noticed the word “DQN” sticks out among Japanese characters. Pronounced ‘Dokyun’, it came from a variety show called Mugumi! Dokyun, which gave life advice to struggling couples. Now, it’s used to describe someone who is stupid and acts without thinking. Because it’s written in romaji, you might assume it’s a typo, but it was completely intentional. However, please note that this term can be seen as insulting or even derogatory.

Just like in English, saying texting slang out loud might be a little out of place, so for in-person conversations, check out our blog: Top 30 Japanese Slangs

Popular Japanese Internet Slang Terms Used on Social Media

Using social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube is super fun (and addicting), but it’s essential to know the text slang terms that are everywhere. This is especially true for Twitter, where brevity is key and phrases need to be shortened, or in text messages, where speed is essential. Let’s check out some awesome Japanese text slang terms frequently used online!

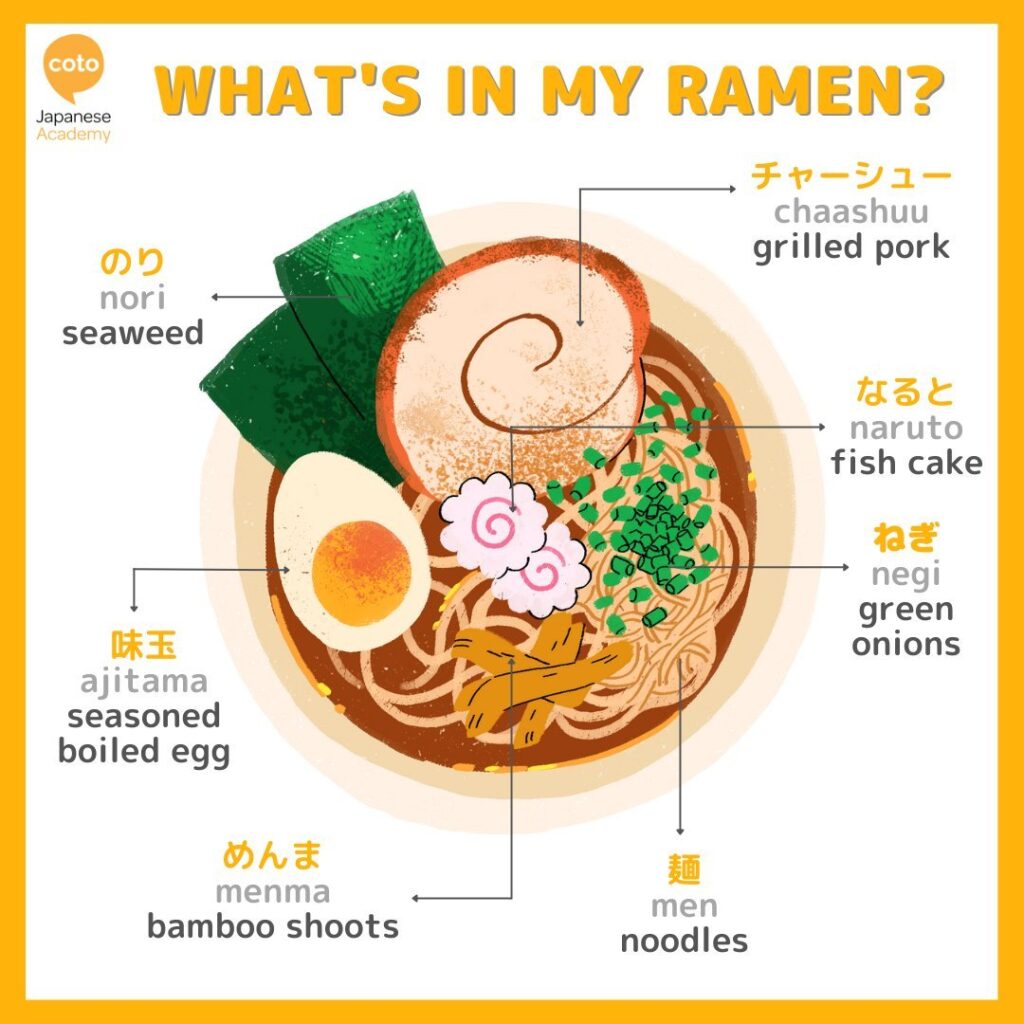

1. 飯テロ (Meshi Tero)

Reading: meshi tero

Meaning: food terror

Do you ever see a photo of really delicious food and get upset that you can’t eat it? This is exactly what 飯テロ is talking about! 飯 (meshi) means food, and テロ (tero) means terror or terrorist; combined, they refer to the act of uploading such pictures on social media that make people hungry (especially late at night)! The more appetizing the food, the more テロ (tero) is unleashed!

Example:

彼はパスタの写真をあげて、飯テロした。

Kare wa pasuta no shashin o agete, meshi tero shita.

When he uploaded those photos of pasta, he did “food terror.”

2. リア充 (Riajuu)

Reading: riajuu

Meaning: Someone who has a fulfilling life offline

We all know it’s not good to spend too much time on the internet. But, for many of us, the internet is key to countless hobbies and interests. However, for リア充, most of their happiness comes from the real world.

Taken from the phrase リアルが充実している (riaru ga juujitsu site iru), which means one’s real-world life is fulfilling, リア充 are usually characterized by having significant others, many friends irl, non-internet-based hobbies, and active lifestyles. In other words, they have a satisfying life away from the internet!

Example:

彼女はピアノを弾いたり、絵を描くのが好きです。リア充です!

Kanojo wa piano o hiitari, e o kakitari suru noga suki desu. Riajuu desu!

She likes to play piano and paint; she is a riajuu!

3. w or 笑 (Wara)

Reading: wara

Meaning: laughing

This is the Japanese version of LOL! The “w” or 笑 (wara) is taken from the beginning part of the verb 笑う (warau), which means “to laugh.” Just like LOL, it’s usually used at the end of a sentence, and the more w’s you add (i.e., wwww), the harder you are laughing. 笑 is usually seen as the more “mature” way to write this, but many just use “w” instead.

Example:

うちの猫、私の枕で寝てるwwww

Uchi no neko, watashi no makura de neteru wara

My cat is sleeping on my pillow lolll

4. 草 (Kusa)

Reading: kusa

Meaning: lol / something hilarious

草 literally means “grass.” It became slang because many “w” characters (wwwww) used for laughter look like grass growing on the screen. So 草 became shorthand meaning “that’s hilarious.” This is very common on forums, gaming chats, and TikTok comments.

Example:

その写真は草生える

Sono shashin wa kusa haeru.

That picture is hilarious (lit. “grass is growing”).

5. 888 (Pachi-pachi-pachi)

Reading: pachi-pachi-pachi

Meaning: clapping sound effects

No words, or even letters, what could a phrase made up of only 8’s mean? Remember that the Japanese love to use onomatopoeia. The onomatopoeia for “clapping” is pachi-pachi-pachi, and eight can be read as either hachi or pachi. So, if you put a bunch of 8’s next to each other, you get the clapping sound when you read it! Most of the time, you will use this to denote congratulations. Just like with “w”, the more 8’s you write, the more clapping you are doing.

Example:

言語学の学位をとったんですね! 888

Gengogaku no gakui o tottan desune! Pachi pachi pachi

You got your degree in Linguistics! (clap, clap, clap)

6. フロリダする (Furorida Suru)

Reading: furorida suru

Meaning: to leave a conversation to have a bath

Yes, this does sound like Florida, but it has nothing to do with the state. Instead, this particular verb is actually a combination of the words furo (bath) and ridatsu (to withdraw), and refers to leaving a conversation (either online or through text) to hop in the tub or shower. A lot of Japanese people soak in the bath before bed, so this word probably came about because so many people take a break from the conversation for their routine bath.

Example:

彼女は、8:45にフロリダした。

Kanojo wa 8:45 ni furorida shita.

She left the conversation to shower at 8:45.

7. KY (Keiwai)

Reading: keiwai

Meaning: A person who cannot read the room

It may be strange to see the Roman alphabet here, but it will make sense in a little bit! KY comes from the expression 空気読めない (kuuki yomenai); this literally means to be unable to read the air. Instead of typing all this out, however, many Japanese people just take the “k” from kuuki and the “y” from yomenai to make this abbreviation!

People who are KY tend to behave in ways considered inappropriate for the situation at hand or are simply oblivious to what is happening around them. This is definitely not something you would want to be called!

彼氏と別れたばかりの友だちの前で、自分の彼氏自慢とか、あの子、KYすぎ。

Kareshi to wakareta bakari no tomodachi no mae de, jibun no kareshi jiman toka, ano ko, KY-sugi.

In front of a friend who just broke up with her boyfriend, she boasts about her boyfriend, and that girl (can’t read the room).

Want to start learning Japanese?

8. なう or ナウ (Nau)

Reading: nau

Meaning: Doing something right now, at a place right now

A lot of people like to use social media to show people what they’re up to. Sometimes, this means letting people know what they’re doing as they’re doing it! If you want to say what you’re doing now, you can just use the word なう (nau)… which sounds almost like now. This makes it pretty easy to remember!

Example:

京都なう/ たこ焼きナウ

Kyouto nau / takoyaki nau

I’m in Kyoto now / I’m eating takoyaki right now

9. 乙 (Otsu)

Reading: otsu

Meaning: Good job! Well done!

Ever want to congratulate someone online, maybe for a good round in a game or in a video comment? 乙 is perfect for this! 乙 stands in for the Japanese phrase お疲れ様でした (otsukare sama deshita), which means thank you for your hard work. Many times, this is said at the end of a workday or after a big task. The kanji 乙 doesn’t have any relation to this phrase; it’s just used for its reading!

10. 炎上 (Enjou)

Reading: enjou

Meaning: to be roasted on social media

Social media can be a wonderful place, but it can also be a harmful one as well; we’ve all seen how common it is for someone to be heavily criticized, or “roasted” online. Leaning into the fire (or roasting) analogy, Japanese netizens started using the word 炎上, which actually means flaming, to describe when this happens.

Example:

彼はそのパンツを履いて炎上した。

Kare wa sono pantsu o haite, enjou shita.

When he wore those pants, he got roasted.

11. オワコン (Owakon)

Reading: owakon

Meaning: Dated content, no-longer-current media

With new content and trends being created every minute, things can get dated on the internet pretty quickly. To talk about content that has already passed its prime, オワコン is the perfect word. It’s formed from a combination of 終わった (owatta, meaning finished) and コンテンツ (kontentsu, meaning contents).

Simply put, it’s content that’s finished being relevant! Now, I wonder how long it will take before this word goes out of date.

Example:

ゾンビ映画はオワコンになってしまった。

Zonbi eiga wa owakon ni natteshimatta.

Zombie movies became dated content.

12. △ (Sankakkei)

Reading: sankakkei

Meaning: Mr./Mrs.___ is cool.

We’ve gone through Japanese internet slang using Japanese abbreviations, Roman letters, and even numbers, but what on earth is a shape doing here? Well, it’s a little complicated. The Japanese word for a triangle is sankakukei, but most people pronounce it as sankakkei, as it’s easier.

The san- in the beginning is pronounced the same as さん, or the honorific title meaning Mr. / Mrs. Then, –kakkei is a short form ofかっこいい (kakkoii), which means cool or attractive. So, put them together, and you get a reading of a triangle that can also mean so-and-so is cool. It’s a play on words that also saves time typing! Japanese netizens often use it to refer to celebrities or anime characters.

Example:

みどりや△ 。

Midoriya san-kakkee.

Mr. Midoriya is cool.

13. ずっ友

Reading: zuttomo

Meaning: friends for life

We all know the abbreviation for BFF – Best Friends Forever. But what if you want to say this in Japanese? Turns out you can call your closest friends ずっ友! Like a lot of words on this list, ずっ友 is a combination of two words: ずっと (zutto), meaning forever, and 友達 (tomodachi), meaning friends. It was first used by young girls taking pictures together, but now everyone uses it, making it the perfect alternative to saying “cheese” when taking pictures with your closest friends!

Example:

旅行の後、ずっ友になりました。

Ryokou no ato, zuttomo ni narimashita.

After their trip, they became BFFs.

14. Wkwk (Waku Waku)

Reading: wakuwaku

Meaning: to be excited

If you’re a fan of the series SPYxFAMILY, one of the popular anime series on Netflix, you might already be familiar with ワクワク (wakuwaku). The all too adorable titular character, Anya, says all the time! ワクワク is an onomatopoeic word meant to imitate excitement!

However, if you’re really excited about something, you may not have the patience to type out the whole word! So many Japanese netizens just type wkwk instead, which is the first letter of each kana (wa, ku, wa, ku). You can use wkwk in a myriad of situations, such as starting a new hobby or finding out your adoptive dad is really a spy in disguise!

Example:

アニャはピーナッツを食べたがっています wkwk。

Anya wa piinattsu wo tabetagatteimasu wakuwaku.

Anya wants to eat peanuts!

15. バズる (Bazuru)

Reading: bazuru

Meaning: to go viral

バズる comes from the English word “buzz,” referring to online hype. If a tweet, TikTok, or video spreads rapidly and gets tons of engagement, people say it “buzzes.” This term is especially popular among influencers or anyone active on X (Twitter).

Example:

この動画、めっちゃバズってる!

Kono douga, meccha bazutteru!

This video is totally going viral!

This term can also be used irl (in real life), too, but mostly among Gen Zs. Check out our blog to keep up with your Gen Z friends: 16 Top Gen Z Japanese Slang and What They Mean

16.りょ / りょ (Ryo)

Reading: ryo

Meaning: got it / okay

りょ(ryo) is a super-short version of 了解 (ryoukai), meaning “Roger that!” or “Understood!” It’s extremely common in casual text messages, especially among teens and young adults. Very similar to texting “k” or “got u” in English.

Example:

6時に駅集合で!

Roku-ji ni eki shuugō de!

Meeting at the station at 6!

りょ!

Ryo!

Got it!

17. 尊い (Toutoi)

Reading: toutoi

Meaning: precious/divine/too pure (often used for fandoms)

尊い is a common slang term used especially in anime, idol, BL, or VTuber fandoms. It expresses feeling overwhelmed by how cute, beautiful, perfect, or emotionally powerful someone or something is. It’s closer to “I can’t handle this, it’s too precious.”

Often paired with crying emojis or kaomoji.

Example:

この2人のシーン、尊すぎる…

Kono futari no shin, toutosugiru…

This scene with these two is way too precious…

18. ググる (Guguru)

Reading: Guguru

Meaning: To Google or to search online

This internet slang comes directly from the Japanese word for Google, グーグル (Guuguru), but it’s a bit shortened and transformed into a verb. You can use this phrase just like you would in English, when something like “we can just Google it.”

You can also conjugate it just like a typical Japanese verb: ググった (gugutta), ググらない (guguranai), ググります (gugurimasu), etc.

Example:

その映画の時間、ググってみて。

Sono eiga no jikan, gugutte mite.

Try Googling the showtime for that movie.

19. サムネ (Samune)

Reading: Samune

Meaning: Thumbnail

サムネ (Samune) is short for the Japanese word for thumbnail, サムネール. You will often see this word on video-sharing platforms, such as YouTube and TikTok. Whenever you want to talk about a video’s preview image, just refer to it as the サムネ.

Example:

そのビデオのサムネがすごく良かったから、バズったよ。

Sono bideo no samune ga sugoku yokatta kara, bazutta yo.

The thumbnail for that video was really good, that’s why it went viral.

20. Ksk (Kasoku)

Reading: Kasoku

Meaning: Faster

Ksk comes from the word Kasoku, 加速, which means to accelerate or go faster. It’s used very frequently across the internet, especially on messaging boards like 2chan or on live video chats. People often use it when they want something to go faster or speed up. It’s similar to saying “go, go, go!” or “faster!”

Example:

コメントもっとkskして!

Komento motto ksk shite!

Everyone, comment faster

21. Ktkr (Kita Kore)

Reading: kita kore

Meaning: “It’s here!!” / “Yes!!” / “Finally!!!”

ktkr is an abbreviation of キタコレ (kita kore), which is a colloquial, excited way of saying “it’s here!” in Japanese! People use it when something they’ve been waiting for finally happens: a game update, a teaser drop, a favorite streamer coming online, etc.

Example:

新しいPV出た!? ktkr!!

Atarashii PV deta!? ktkr!!

The new promo video dropped!? It’s finally here!

Japanese Texting Culture: Kaomojis (*^_^*)

Finally, we can’t finish an article about Japanese internet and texting slang without touching on kaomoji. Kaomojis, or literally face characters, are simple faces or facial expressions created using different elements and symbols found on your keyboard. You can almost think of them as old-school emojis! Just like emojis, kaomojis help to make the meaning of your words clear and to emphasize certain feelings. There’s a lot of focus placed on the kaomoji eyes, which makes them very expressive and particularly appealing to Japanese netizens. Many users place them at the end of a sentence or idea, or even just by themselves!

A lot of kaomojis are clear as to what they mean, for example:

- (^_^; ) – means being embarrassed

- (-_-)zzz – means being asleep

- (T_T) – means crying

Some aren’t as intuitive, for instance:

- m(_ _)m – means being apologetic (bowing) with the “m” representing your hands and the “(_ _)” representing your head.

- (#`Д´) – meaning angry. This symbol, `Д´, represents an angry face with the “#” representing yelling.

However, the more you see kaomojis and get used to them, the more you will be able to pick up on their meaning! Check out the Kaomoji: Japanese Emoticons website if you ever need to find out what a particular kaomoji means!

Have you ever wondered what the Japanese kanji emojis meant? Check out our blog to learn everything you need to know: Japanese Kanji Emojis: What Do They Actually Mean?

Conclusion

Whether it’s on social media, online games, or just chatting with friends, slang is bound to pop up everywhere you go. Being well-versed in Japanese slang will not only help you navigate Japanese internet communities but also make new Japanese friends. Hopefully, now that you have this list of Japanese internet and texting slang, navigating the Japanese web will be a bit easier! The next time you reach that one word, you’ll already know what it means.

Want to talk more like a Japanese native and get more practice in speaking Japanese? Why not check out some of our classes at Coto Academy? We focus on fun, practical lessons. We also have online courses, which would be the perfect place to practice what you’ve just learned! Fill out the form below for a free level check and course consultation.

FAQ:

What are some popular Japanese internet slang terms and expressions used on social media platforms?

Some popular Japanese internet slang terms and expressions used on social media platforms include “w” (short for “warai” meaning laugh), 888 (pachi pachi pachi, meaning clapping), pkpk (pakupaku, meaning excited), and りょ(ryo, meaning “got it!).

Why is it important to know Japanese internet and text slang terms when communicating online with Japanese speakers?

Unlike Japanese spoken in real life, internet slangs make more use of abbreviations, acronyms, and even emoticons, which can be hard to understand if you don’t actually understand online Japanese lingo. Although these slang phrases aren’t found in textbooks (though they should start to be), they are essential if you want to actually communicate and engage people online in Japanese.

How do Japanese internet and text slang terms differ from traditional Japanese language?

Japanese internet and text slang terms differ from the traditional Japanese language in various ways. They are often shorter and more casual, incorporating English words and expressions. Additionally, they can change rapidly over time, making it essential to stay updated with the latest trends.

Can Japanese internet and text slang terms be offensive or inappropriate to use in certain situations?

Yes, some Japanese internet and text slang terms can be offensive or inappropriate to use in certain situations. It is crucial to understand the context and appropriateness of these terms to avoid offending others or using them in an inappropriate way. It’s always best to err on the side of caution when using internet slang in any language. Like any slang used across the internet, it’s best to understand the full context before deciding to use it yourself.

What’s the difference between kaomoji and emojis?

While both generally represent facial expressions, emojis are pictograms embedded in text, whereas kaomoji (lit. face characters) are created by the writer using symbols on the keyboard. They both serve a similar purpose to use emoticons to represent general emotions, but kaomoji can be harder to understand if you’re not used to recognizing what facial expression or emotion is being conveyed.

Like reading this blog? We recommend that you check out: