Planning to drive in Japan? Even if you’re just walking or cycling, it’s important to recognize key traffic and street signs to stay safe. Japan’s road signs combine international symbols with unique designs shaped by local traffic laws, which can make them confusing at times.

Whether you’re planning a road trip, studying to get a driver’s license in Japan, or just curious, understanding these signs can help you navigate safely and avoid fines. This guide covers the most common Japanese road and street signs with images and explanations.

Types of Japanese road signs

Before we dive in, we need to learn about the types of road signs. For example, some might be giving demands that you must follow by law, while others are giving directions. There are three general categories for signs, which include:

- Regulatory signs: These signs display road regulation information in order to maintain road safety and prevent hazards. They usually show mandatory actions or prohibitions.

- Warning signs: They usually provide a warning about something coming ahead, from sharp turns to possible hazards such as animals or slippery surfaces.

- Information and guide signs: The signs give information on navigation and location information, such as which direction roads may go or where you are allowed to go on certain lanes.

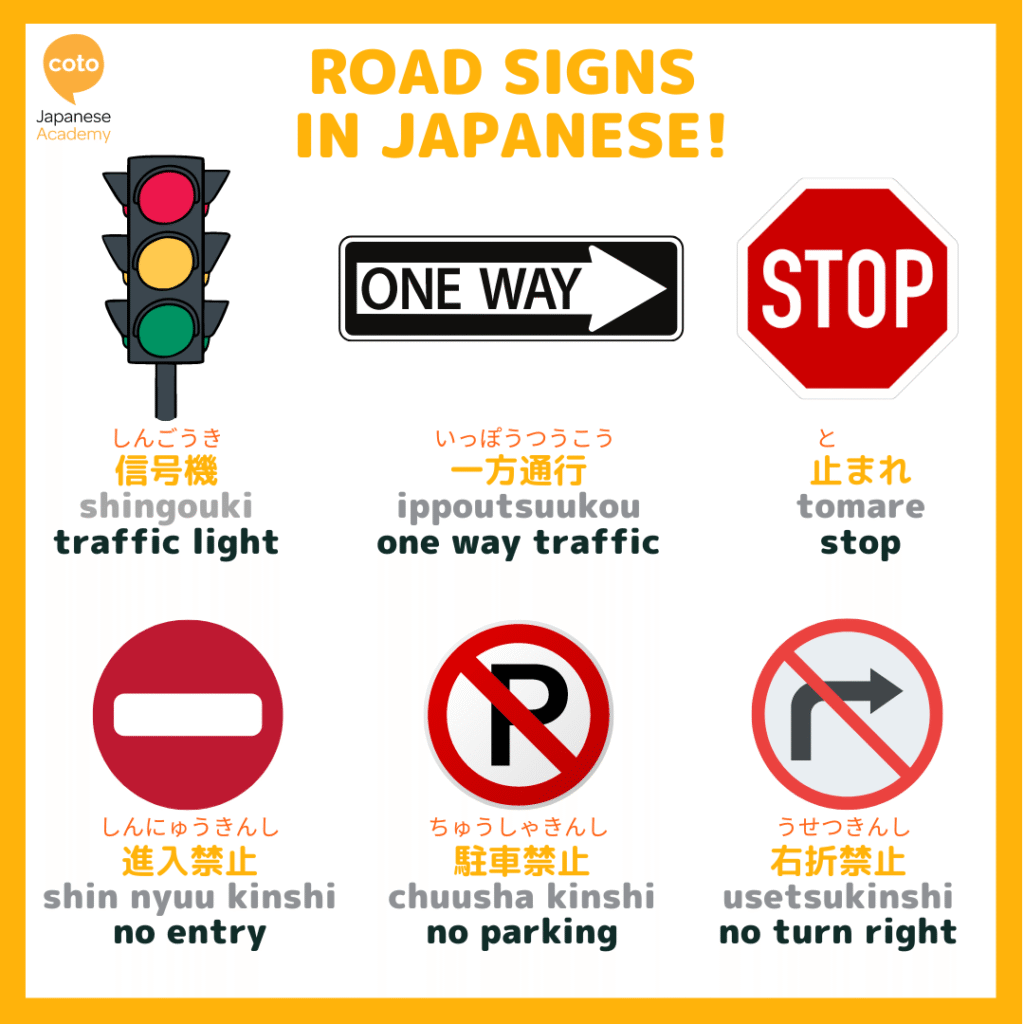

Below is an infographic showing the Japanese terms for common road and street signs found in the West. You might notice the signs in Japan are different:

Common Japanese road signs to know

Now let’s discuss some of the most important road and street signs to be aware of to avoid fines, dangers, and navigate Japanese streets safely, whether you are a biker, pedestrian, or driver of any vehicle (motorbikes, cars, trucks).

Many of these signs do have kanji and sometimes hiragana, so read our guide on Japanese writing systems. Additionally, you can drill some of the kanji we discuss with one of our recommended kanji learning apps.

1. Road Closed

This sign with a red X in the center and the character 通行止 (tsuukoudo) means the road is closed to everyone, including pedestrians, bikes, vehicles (motorbikes, cars, trucks, and more), and trains.

Kanji: 通行止

Furigana: つうこうどめ

Romaji: Tsuukoudome

Meaning: 通行 (tsuukou) means to pass, and 止 (dome) means to stop.

So, together the word literally means stop passage but is used to mean road closed.

2. Closed to Vehicles

This sign, with just one red slash across the center, indicates the road ahead is closed to all vehicles, but pedestrians are permitted.

3. Vehicles Prohibited

Similar to the previous one, this sign indicates that all vehicles are prohibited from entering the area.

4. Closed to vehicles with more than 2 wheels

The sign on the left indicates that cars and other vehicles with more than 2 wheels are not allowed to enter. The sign on the right also prohibits motorbikes and other 2 wheeled vehicles.

5. Permitted Marked Directions

These signs with a blue background and white arrows in the center point to the directions you are permitted to go. These signs can have arrows indicating virtually any direction. The above are just a couple of examples; the sign at the top permits proceeding left or straight, and the bottom indicates you can proceed straight, left, or right.

6. No Crossing

While normally you are allowed to cross the center line of the road to enter something, such as a parking lot, the sign indicates that crossing is not permitted.

7. No U-turning

This sign shows that U-turns are prohibited on the road you are currently driving on.

8. No Passing

This sign prohibits overtaking other vehicles on the road, which is normally allowed on any street with more than one lane. This sign may be present when there isn’t a passing lane or when the road doesn’t allow enough space for passing other vehicles

9. No Parking

These signs indicate the area does not allow parking, with the top road sign prohibiting both stopping and parking. The sign on the bottom only prohibits parking, but stopping for under 5 minutes is permitted. The number at the top of the signs, “8 – 20,” indicates the time zone (8:00 am to 8:00 pm) when the prohibitions are valid. Outside of that time, parking or stopping is permitted.

10. Time Limited Parking

This sign allows parking for a limited time. In this sign, the number “60 分 (pun)” meaning 60 minutes following the P for parking, allows parking for a total of 1 hour. This time restriction is valid from 8:00 am to 8:00 pm as indicated by the top “8-20” numbers.

Read our guide to understand how to read and say minutes and hours in Japanese!

11. Maximum Speed Limit

This sign with a number in the middle indicates the maximum speed in kilometers per hour (kph) you are allowed to reach in any vehicle. In this case, the sign allows a maximum speed limit of 50 kilometers per hour.

Keep in mind that Japanese society uses the metric system, so don’t interpret them as 50 miles per hour.

12. Minimum Speed Limit

This is a minimum speed limit sign (in kilometers), as indicated by a number with an underline. Minimum speed limit road signs may not be too familiar, depending on where you come from, but in Japan, they are mostly found on highways and express lanes to prevent traffic blockage.

13. Motor Vehicles Only

This sign shows the permitted vehicles or pedestrians that are allowed to use the road. In this case, only motor vehicles are allowed to be used. However, bicycles, motorbikes, light vehicles, and pedestrians are not permitted to use the road.

14. Bicycle Only

This sign shows the road only permits bicycles; pedestrians and motor vehicles are not allowed.

15. Pedestrian Only and Pedestrian & Bicycle Only

The sign on the left indicates pedestrians only. N bikes or vehicles of any kind are permitted. The sign on the right allows bicycles and pedestrians only; no vehicles are allowed.

16. One Way

One-way signs, which are always rectangular, blue with a white arrow in the center, indicate that the road only goes in the direction the arrow is pointing. It is often used to indicate the road is not a 2 way street. In this case, the road only goes left, but these signs can point to other directions.

This sign is not to be confused with the marked directional signs discussed above, which are round in shape.

17. Dedicated Lane

This sign shows that the designated lane only allows buses with the kanji 専用 (senyou), meaning exclusive use, with the image of a bus above it. Dedicated lane signs can include other vehicle types, such as motorbikes or cars.

Kanji: 専用

Furigana: せんよう

Romaji: senyou

Meaning: 専 (sen) means exclusive or special, and 用 (you) means to use.

Together, the word translates to special usage or exclusive usage.

18. Bicycle Lane

The bicycle lane sign shows that the designated lane is meant for bicycles only, with the characters 専用 (senyou) meaning exclusive use. This sign uses the same kanji characters as above, but this time with a bike and clear lines separating the lane from the main road meant for vehicles.

19. Priority Lane

The priority lane shows that certain vehicles should be given special priority, which is a bus in this case (priority lanes are mostly used for buses). The character 優先 (yuusen) just translates to priority. Other vehicles can use the designated priority lane, but must give buses the right of way by yielding.

Kanji: 優先

Furigana: ゆうせん

Romaji: Yuusen

Meaning: 優先 is equivalent to “priority” in English.

20. Direction Specific Lanes

These signs show the specific direction permitted on each lane. Some signs, like the one on the top, can show the specified directions of each respective lane on the road. The sign on the bottom shows the permitted directions a vehicle can proceed on only 1 lane.

21. Clockwise Roundabout

This sign shows that the oncoming roundabout goes in a clockwise direction.

22. Permitted Angle For Parking

These parking signs show the angle you are allowed to park relative to the side of the road (indicated by the white line). The sign on the top shows vehicles are permitted to park perpendicular to the roadside. The sign on the bottom shows vehicles are permitted to park parallel to the side of the road.

Kanji: 直角駐車

Furigana: ちょっかくちゅうしゃ

Romaji: chokkaku chuusha

Meaning: 直角 means right angle or perpendicular, and 駐車 means parking, so the whole expression means perpendicular parking.

Kanji: 平行駐車

Furigana: へいこうちゅうしゃ

Romaji: heikou chuusha

Meaning: 平行 means parallel, and 駐車 (chuusha) means parking, so the whole expression means parallel parking.

23. Sound Horn

This sign requires drivers to sound the horn while driving.

24. Slow Down

This sign requires drivers to slow down (徐行), generally to a level where the vehicle can stop immediately without skidding.

Kanji: 徐行

Furigana: じょこう

Romaji: Jokou

Meaning: 徐 (jo) means slow or gradual, and 行 (kou) means to go. So, the expression means go slow or slow down.

25. Stop

This is equivalent to the stop sign common in many Western nations, this one of the road signs that are distinct to Japan. This sign is always triangular-shaped and red with 止まれ (tomare), meaning stop, written in white at the center.

Kanji Review

止まれ (tomare): comes from the verb, 止まる, meaning to stop, but is conjugated into imperative form as 止まれ as a demand or order for you to stop.

26. Closed to Pedestrians

This sign communicates that pedestrians are not allowed to enter the area with the text saying 通行止(Tsuukoudome) or stop proceeding.

Kanji: 通行止

Furigana: つうこうどめ

Romaji: tsuukoudome

27. No Pedestrian Crossing

The sign prohibits pedestrians from crossing the road with the text 横断禁止 (oodan kinshi), meaning crossing prohibited.

Kanji: 横断禁止

Furigana: おおだんきんし

Romaji: Oodan kinshi

Meaning: 横断 (oodan) means crossing, and 禁止 (kinshi) means prohibited, so the expression on crossing prohibited

28. Intersection and Sharp Curve Ahead

These are warning signs that inform drivers of potential hazards ahead. From top to bottom, the signs show there is an intersection, curved roads, and sharp turns ahead, so drivers can prepare by slowing down.

29. Railroad Crossing

A sign showing there is a railroad crossing ahead.

30. Train Crossing

A warning sign showing there is a train crossing ahead.

31. Slipper Road Ahead

A warning sign that shows there could be slippery roads ahead, which could be due to terrain and weather conditions like sand, ice, or rain.

32. Traffic Light Ahead

This sign shows that there is a traffic light ahead and is usually present on high-speed expressways so drivers can slow down in time to stop at the light.

33. Falling Stones Ahead

This is a warning sign about potential falling stones from cliffs and mountains ahead.

34. Steep Road Ahead

Steep uphill road sign with the number indicating the road ahead will slope at an incline of 10 degrees. Signs can show slopes with differing numbers of degrees. There are also signs that warn of steep road declines.

35. Uneven Road Ahead

This sign warns drivers that the road ahead will be uneven and bumpy.

36. Cross Winds Ahead

The cross-winds sign warns drivers that the road will likely have strong crosswinds and could impact the movement of the vehicle.

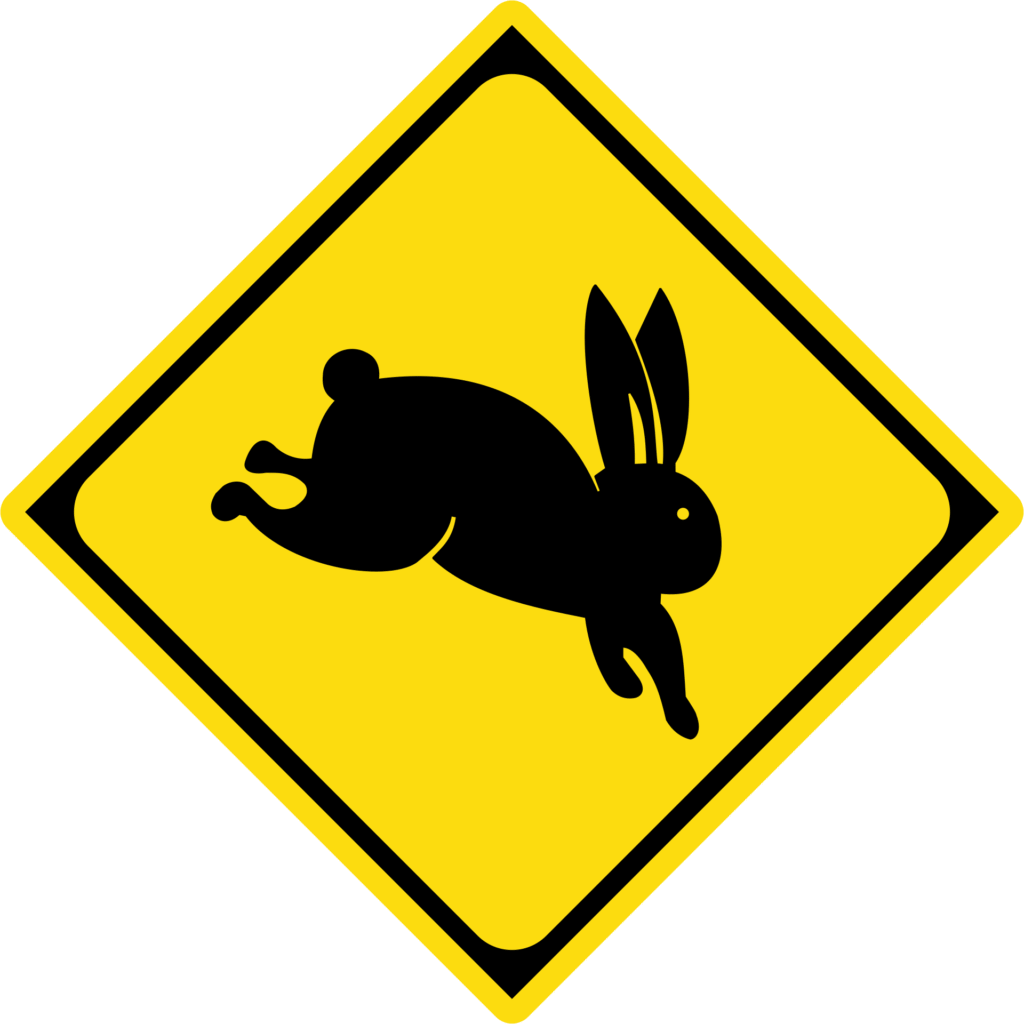

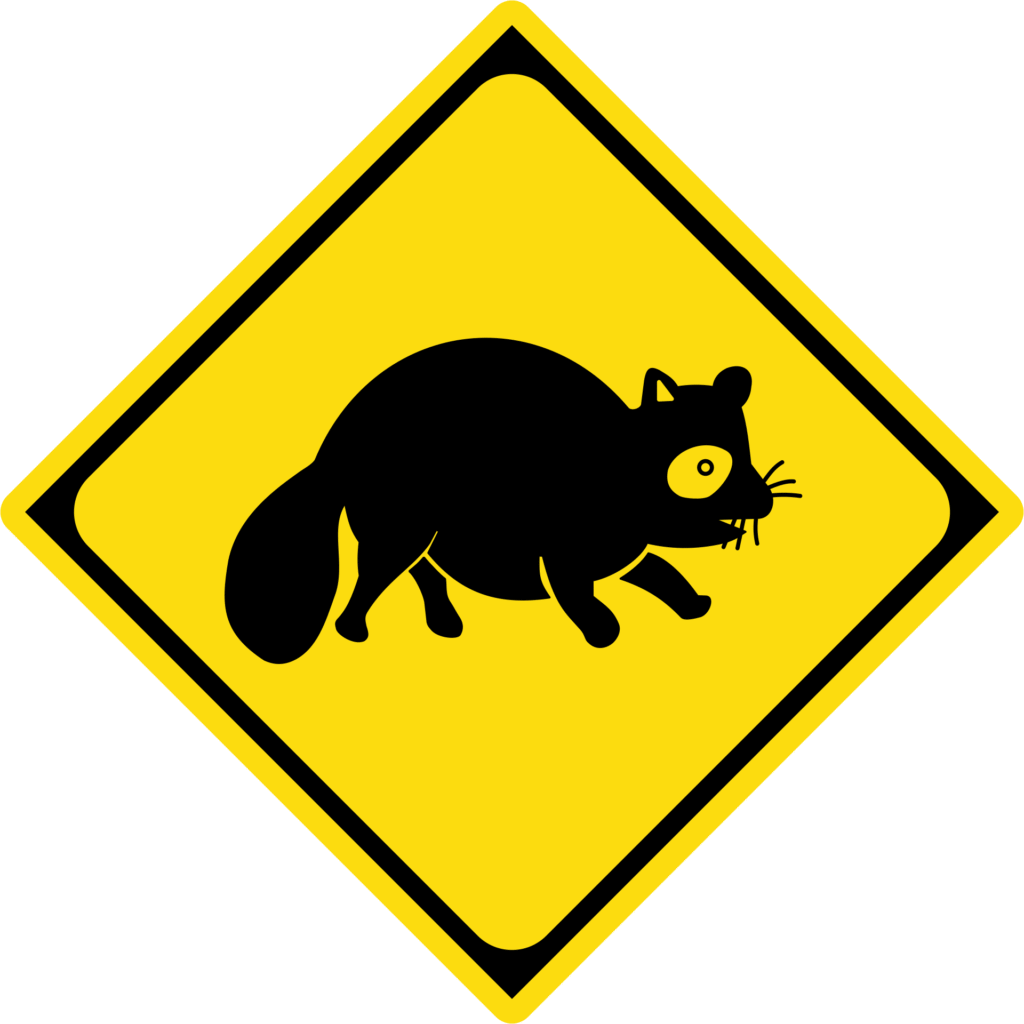

37. Be Aware of Animals

This sign just warns of potential animal populations that could jump onto the road. The signs seems to show a deer, a rabbit, and a raccoon, respectively, but the sign could use other images of common animals in the area. Also note that the animal on the sign is not the only creature that could appear on the road, and may just be used to be on the lookout for animals in general.

38. Other Dangers Ahead

This sign just cautions drivers of general potential dangers ahead on the road.

39. Parking Allowed

This sign with a large white P in the center indicates that parking and stopping are permitted.

40. Driving on Tracks Allowed

This sign indicates that driving on the train tracks is permitted. Oftentimes, this sign may include specific vehicles permitted to drive on the tracks.

41. Stopping Allowed

This another road sign unique to Japan. The sign says 停 (tei), which means stop, but in this case, this sign indicates that stopping is allowed if you need to stop along the road temporarily, but this is not a stop sign that demands you must stop.

Kanji: 亭

Furigana: てい

Romaji: tei

Meaning: 停 means to stop, similar to 止まる (tomaru).

42. Center Line

The sign says 中央線 (chuuou sen) with an arrow pointing directly downward, indicating the position directly below the sign is the center line of the road.

Kanji: 中央線

Furigana: ちゅうおうせん

Romaji: chuuou sen

Meaning: 中央 (chuuou) means center or central, and 線 (sen) means line. So, the expression means center line.

43. Stopping Line

The sign says 停止線 (teishi sen), which means stop line. This sign indicates the line on the road where vehicles can stop.

Kanji: 停止線

Furigana: ていしせん

Romaji: Teishisen

Meaning: 停止 (teishi) means stop or stoppage, and 線 (sen) means line. Together, the word means stoppage line.

44. Pedestrian Crossing

This indicates that there is a pedestrian crossing up ahead, so you would need to stop if pedestrians are crossing the road.

45. Safe Area

This sign indicates that the following area is a safety zone for pedestrians to get off and on trains or for pedestrians to cross the road. No vehicles are allowed in this area.

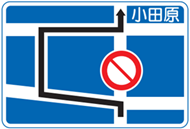

46. Regulation Notice

These signs are notices that roads or streets are closed beyond the point of the sign. The sign on the left shows where you can detour to go around the closed road. The sign on the right just indicates that the road for the next 100m is closed from 8:00 am to 8:00 pm.

47. Service Area and Roadside Station

The sign indicates that there is a service area coming up in a number of kilometers. In this case, the sign says the service area will be 5 km at the top and 9 km at the bottom. These signs are mostly found in expressways where drivers would need to exit the road to access any kind of services.

However, service areas are more convenient since you would not need to completely exit the IC gate, which charges you every time you enter and exit. Usually, service areas have places to eat, get gas, and may offer certain services for your vehicle, such as minor repairs.

Navigate the road by knowing Japanese!

Japan’s road signs combine visual symbols with written instructions. Still, learning to navigate Japan and understand certain signs may require some Japanese, especially if you want to ask for directions. So, consider Coto Academy’s in-person or online Japanese classes to receive professional coaching and instruction in practical Japanese conversation, reading, and writing!

Fill out the form below to sign up right now!

FAQ

Are Japanese road signs in English?

Many are bilingual, especially in urban areas and on highways, but smaller roads and areas outside busy city centers may have only Japanese text.

Do I need to know Japanese to drive in Japan?

Not strictly, but understanding key signs is highly recommended for safety.

Are Japanese road signs similar to those in other countries?

Many are based on international standards, such as warning signs in yellow diamonds. However, some, like the triangular stop sign with “止まれ”, are unique to Japan.

What should I know about parking signs in Japan?

A blue “P” sign indicates legal parking. A red-bordered circle with “駐車禁止” means No Parking, and one with “駐停車禁止” means No Stopping or Parking at any time.

What does “優先道路” (Priority Road) mean?

It means your road has the right of way at intersections, and other vehicles must yield. This is especially useful in rural areas where traffic lights are sparse.

Navigating Japan, by road, rail, or sea? You might find this helpful:

- Common Japanese Train Announcements Phrases and Their Meaning

- How to Get Around Japan with Public Transportation: Buses, Taxis and Train

- How to Buy a Commuter Pass in Japan

- Guide to Using the Train in Japan Without IC Cards

- What to Do When You Lose a Commuter Pass in Japan

- Common Public Signs in Japanese