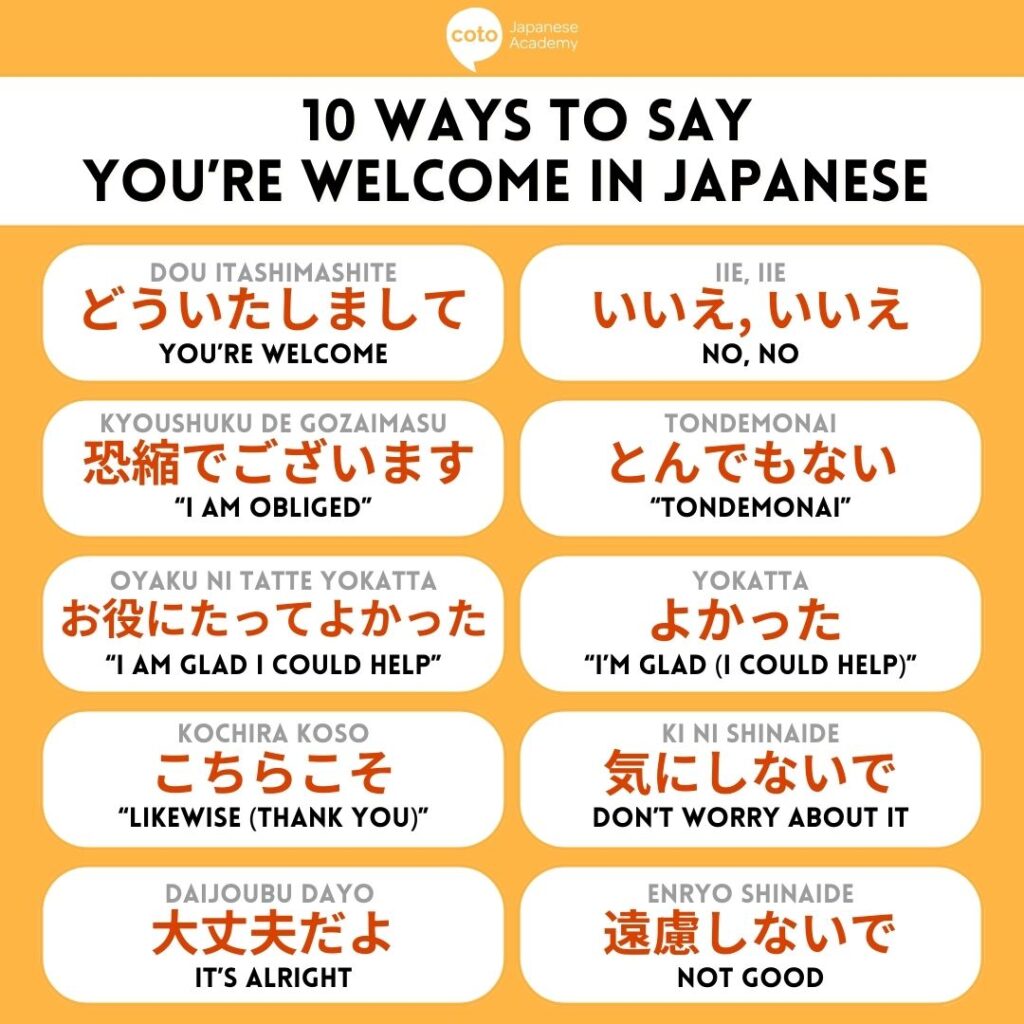

You have probably heard that Japanese people are known to be polite, so it’s no surprise that they take saying “you’re welcome” as seriously as showing gratitude itself (almost!). Similar to how there are many ways to say thank you in Japanese, there are several ways to say you’re welcome as well.

As you will see, it is important in Japanese culture to always remain polite even when accepting gratitude from someone. Oftentimes, politeness would mean to stay humble and modest by undermining the impact of your goodwill or even completely denying that you are owed any gratitude.

So, today we’ll cover 10 different ways in which you can say “you’re welcome!” in Japanese for both casual and formal situations.

Watch Our Video on You’re Welcome in Japanese!

Learn a few ways to say “you’re welcome” in Japanese with our short crash course video.

Basic Way to Say “You’re Welcome!” in Japanese: Dou Itashimashite

Let’s start with the most common way people learn to say “you’re welcome!” in Japanese, どういたしまして (dou itashimashite). More often than not, this is the first word that pops up when you look up “you’re welcome” in a Japanese dictionary.

Douitashimashite is a form of Japanese keigo, or the respectful language used for formal occasions or business settings. The phrase literally translates to “how did I do,” which acts as a humble way of saying I don’t deserve your gratitude. Breaking down the word:

- Dou (どう) means how

- Itashimashite (いたしまして) is the keigo form of suru (する) meaning to do

Originally, it was used to express humility and to deflect praise. In modern Japanese, however, it functions simply as a polite response to thanks, acknowledging the other person’s gratitude.

Pro tip: If you are having a hard time remembering, douitashimashite sounds similar to “Don’t touch my mustache” when said very quickly. Just try it! Even if they don’t sound too similar to you, this tip might still help you remember anyway!

Is “Dou itashimashite” used often?

So, douitashimashite is not used too often. In fact, the phrase is rarely used in casual conversations. Just like saying “you’re welcome”, it comes off rather formal and a bit rigid. It might sound out of place even in the workplace.

Depending on tone, it may feel like you’re “formally accepting” thanks, which can come across as distancing yourself from the other person. Because Japanese communication values modesty, people often avoid phrases that might sound like they’re putting themselves in the spotlight. So for these reasons, the Japanese tend to use other phrases instead.

Ways to Say You’re Welcome in Japanese in Formal Situations

1. 恐縮でございます (Kyoushuku de gozaimasu)

The first of which would be “恐縮でございます (Kyoushuku de gozaimasu)“. It is one of the most formal ways to say “you’re welcome.” The word “恐縮 (kyoushuku)” refers to feeling obliged. The word “でございます (de gozaimasu),” on the other hand, is the keigo form of です or “to be.”

When put together, the phrase would refer to “I am obliged,” or so you would say in a formal situation when somebody thanks you.

2. お役にたってよかった (Oyaku ni tatte yokatta)

Moving on, we take a look at the phrase: お役に立ってよかった (oyaku ni tatte yokatta). “お役に立って (yaku ni tatte)” refers to being helpful or useful. By adding the honorific prefix “お (O)” to the front of the word, we can, in turn, make it sound more polite towards the other party.

“よかった (Yokatta)” can be translated to “I’m glad,” and can even be used alone as a casual way of saying “you’re welcome,” which we will discuss further below. So, combining the two, the phrase or expression means, “I am glad that I was of use to you.” This expression works well for work settings and can even be used casually when dropping the お (o) from 役にたって(yaku ni tatte).

3. こちらこそありがとうございます (Kochirakoso arigatou gozaimasu)

Last but not least, another phrase you can use is こちらこそ (kochira koso). “こちら (kochira)” refers to over here, but can also refer to me or myself. “こそ (koso),” in this context, can be used to emphasize the preceding word.

This term is widely used as a response to someone saying “thank you,” even though it does not really mean you’re welcome. The phrase is a polite way of saying “I should be thankful instead”. “

So combined, they mean, “Surely it should be me who should thank you.” This expression can often be used when someone thanks you for something, but you would also like to thank them back.

For example, you could be working together on a challenging project with your partner or your boss, and when they tell you, “Thank you for your hard work”, you can respond, こちらこそありがとうございます (it is I who should be thankful).

So, keep in mind, this phrase sits on the line between formal and casual. You can say it formally by adding arigatou gozaimasu or casually by just saying arigatou.

Ways to Say “You’re Welcome!” in Japanese in Casual Situations

Being a bit formal can be out of place in certain situations or even a little stiff. There are more casual expressions for when you should ease up a little and just respond naturally and casually.

4. いえいえ (Ie ie)

First up, let’s take a look at “いえいえ (ie ie).” When taken literally, the phrase itself means “no, no” in Japanese. This is typically used when someone is expressing their innermost gratitude towards you. However, all you wanted to tell them was something along the lines of “Nah, don’t mention it.”

This is a very popular and casual way to say “you’re welcome” in Japanese. It is still considered polite even among your colleagues and is a nice way of saying, “No, need to thank me”. You can also use this expression in combination with other phrases.

For example, you can say いえいえ、こちらこそありがとう (ieie kochirakoso arigatou), to say something like “no, no, I should thank you”.

5.とんでもない (Tondemo nai)

Next, we take a look at “とんでもない (tondemonai).” It is a phrase used to indicate that “it’s nothing” in a casual conversation. Usually, some Japanese people use this as an informal way of saying “you’re welcome” as well.

The literal translation of tondemo nai is “there is no way” or “there is no possibility”. But the implied meaning in conversation is “there is no need to thank me”.

You could even use it in conjunction with いえいえ(ie ie).

いえいえ、とんでもないです

Ie ie tondemo nai desu.

No no, it’s nothing.

6. よかった (Yokatta)

Next up, we have “よかった (yokatta)“. This phrase would usually be “I’m glad.” The term literally translates as “was good,” but when the phrase is used alone, it usually means “I’m glad.” So, when you want to use it as an alternative to “you’re welcome”, you can use it to say expressions such as “I’m glad I could help” or “I’m glad you liked it”. By using yokatta to follow up phrases such as 好きで (sukide) or 助けになれて(tasukeni narete), you can say the following:

好きで、よかった

Sukide yokatta

I’m glad you liked it.

助けになれて、よかった

Tasuke ni narete, yokatta

I’m glad I was able to help.

So, this is another great phrase that’s both casual and natural while not sounding too stiff. You can use yokkata in a variety of circumstances to express your happiness that the person you’re speaking to appreciates or is grateful for what you did or what you gave them.

7. 気にしないで (Ki ni shinaide)

Another word that’s occasionally used is “気にしないで (Kinishinaide).” The phrase means “no worries,” but can also be used in certain contexts to say “you’re welcome.”

For example, someone may go on to say something like “Oh my, thank you so much, is there anything I can do to repay you a favour?” in Japanese. In this case, you can simply use the word “気にしないで (Kinishinaide)” to tell them, “It’s okay, no worries.”

8. いえいえ、いつでも声かけて (Ie ie itsudemo koe kakete)

Lastly, we look at a phrase known as “いえいえ、いつでも声かけて (ie ie, itsu demo koe kakete)“. The phrase itself is composed of “いえいえ” and “いつでも声かけて”. Of which, the former we had covered in an earlier part of this section.

This uses the phrase we covered earlier, “いえいえ” plus “いつでも声かけて”.

Let’s take a look at the latter part, “いつでも声かけて.”

いつでも translates to anytime, and 声だけてmeans “please let me know”. So, the whole phrase means “I’m here for you if you need help” or “Let me know if you need help again.”

Adding the two together would make the phrase mean, “It’s fine. Let me know if you ever need help again!”

9. 大丈夫だよ (Daijoubu dayo)

You may have heard the term daijoubu as a way to say “it’s alright” or “it’s okay”. It can be used as a very casual way of saying you’re welcome. Saying “daijoubu dayo” in response to someone thanking you would be similar to saying “it’s okay, don’t worry about it”. It’s a very casual and friendly way of telling someone they don’t need to thank you, but it’s best used among friends and family.

10. 遠慮しないで (Enryo shinaide)

The word 遠慮 (enryo) means “restraint” or “holding back,” and しないで is the negative form of the verb suru (“to do”), meaning “don’t do.” Together, 遠慮しないで literally means “don’t hold back” or “don’t restrain yourself.”

Normally, the imperative form in Japanese can sound rude, especially in its negative form. However, in the case of 遠慮しないで (enryo shinaide), it works well as a way to say “you’re welcome.” Here, you’re essentially telling the other person, “Don’t hesitate to ask for help next time.” It’s commonly used to encourage someone to feel at ease, go ahead, or act freely without holding back.

If you want to use 遠慮しないで (enryo shinaide) in the context of responding to thanks, it can work as a casual way of saying “You’re welcome” with the nuance of “Don’t mention it” or “No need to be shy about it.”

助けてくれてありがとう!

Tasukete kurete arigatou!

Thank you for helping me!

遠慮しないで。

Enryo shinaide!

Don’t mention it!

Go beyond saying you’re welcome and speak Japanese confidently!

Just like in English, saying “you’re welcome” all the time sounds rather formal and stiff, so naturally you will use other words that express something similar. In Japanese, it’s no different! Try remembering some of the expressions above and using it next time someone says “Thank you”.

Of course, speaking Japanese fluently goes beyond memorizing phrases. Build your confidence and conversational skills by joining the fun, flexible lessons at Coto Academy! Our beginner course covers the essentials—from hiragana and katakana to grammar—so you can start speaking Japanese in just four weeks.

We currently offer classes in Tokyo and Yokohama, as well as online classes, with a maximum of eight students per class. You’ll learn from native, professional instructors who make lessons both effective and enjoyable.

Ready to get started? Fill out the form below to contact us!

FAQ

How do you say "you're welcome" in Japanese?

The most common and polite way is どういたしまして (dō itashimashite). For informal situations, いえいえ (iie iie) or とんでもない (tondemo nai) are often used.

What is the polite way to say "you're welcome" in Japanese?

Use どういたしまして.

What are some casual ways to say "you're welcome" in Japanese?

There are many casual ways of saying you’re welcome in Japanese. The most common include いえいえ (ie ie), とんでもない (tondemonai), or even 大丈夫だよ(daijoubudayo).

Are there regional variations in how to say "you're welcome" in Japanese?

You could use いえいえ or とんでもない.

Are there regional variations in how to say "you're welcome" in Japanese?

While these are the most common ways, regional variations or nuances may exist.

Do Japanese people often say どういたしまして (Dou itashimashite) to say you’re welcome?

Similar to saying “you’re welcome in English, it can come off a bit stiff or as if you deserve to be thanked. So, generally people will use other phrases to acknowledge someone’s gratitude without sounding so distant.

Love reading our blog? You might be interested in: