The word keigo (敬語) is written with the kanji that means “to respect” (敬) or “to admire” and the kanji for “language” (語). Japanese society has always cared for hierarchy to the point that honorific speech seems to be a whole other language. If you’re planning to build a fulfilling career in Japan, knowing business Japanese will help you stand out during your job search.

Whatever the reason you are studying Japanese, we believe you are having fun. You enjoyed writing your first hiragana and katakana. Gradually, you were able to express yourself and hold a steady casual conversation in Japanese. Or, at least, that was at the beginning.

As you reach the intermediate step, the fun fades away, and you are shaking your head in despair as you try to understand Japanese honorific speech.

So in this article, we’re guiding you through all the nooks and crannies of Japanese keigo, from the viewpoint of a non-native. We’ll discuss the honorific forms, humble forms, conjugations, and phrases.

Want to boost your career in Japan? Coto Academy’s 3-month Business Japanese Course is designed to help you master keigo (business Japanese) and improve workplace communication skills. Gain the confidence to speak professionally with colleagues and clients, navigate meetings, and open up new career opportunities!

Introduction to Japanese Keigo

Do you know that Japan had a caste system in the past? Until the Meiji restoration, people in different castes would not speak the same Japanese as a form of respect for social ranks. Despite the disappearance of the caste system, honorific speech is still used to mark the degree of intimacy or social standing between people.

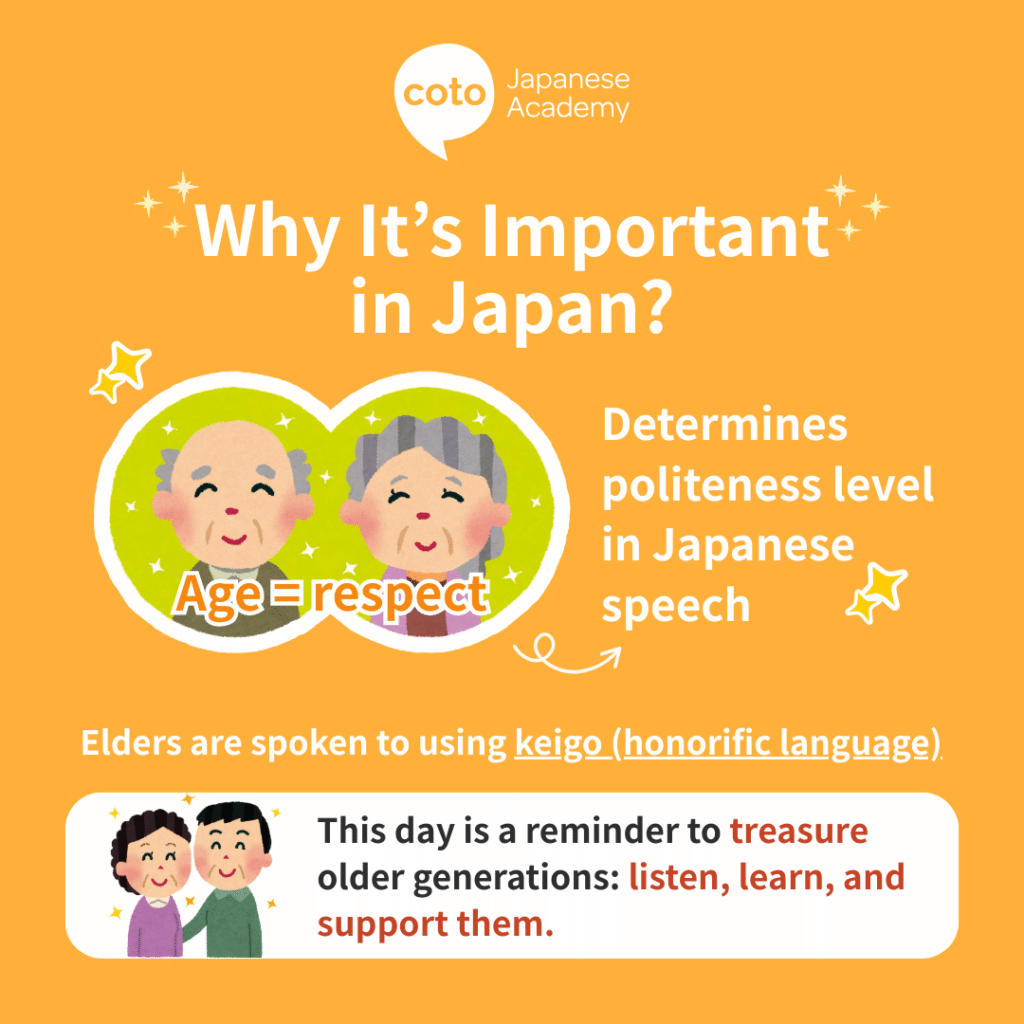

To use keigo is to show your consideration and respect for a person older than you or someone with a higher social standing. Age isn’t the only factor. It can be based on a different position or experience in a company, like your senpai (someone who’s more senior). Your speech will differ accordingly to the person in front of you: a friend, a colleague, a chief, or a client; and to whom you a referring to yourself, your friend, colleague, or client.

But don’t believe keigo speech is easier for native speakers, too. Japanese kids learn keigo the hard way, as they enter junior high school and are confronted with the Japanese hierarchy. Suddenly, they have to mark the difference between 先輩 (elder students) and 後輩 (junior students).

If the thought of learning a whole new style of speaking Japanese sounds scary, then you are not alone. Memorizing keigo is a challenge for even Japanese people so it’s good to know that we’re all in the same position. Very often, Japanese people will not learn keigo in school, but during intensive training sessions before they start their first job.

The Concept of Uchi and Soto

To better understand respectful speech, take a peek into the Japanese concept of uchi and soto, or “in-out” (内-外). The idea might seem simple: uchi (内) literally means “inside”, while soto (外) means “outside”. But both words aren’t just about the physical position. They’re used to describe social distance, too.

The concept of uchi and soto shapes Japan’s culture. In sociology and social psychology, there is the concept of “in-group” and “out-group”, and the Japanese society takes this matter more seriously — so seriously, in fact, that it plays a significant role in its language.

Basically, an in-group is the social group that you identify as a member of. Out-group, on the other hand, is a group that doesn’t fall into the in-group.

In Japanese, 内 means home. As a concept, uchi (内) reflects in-group and refers to all the people you know inside a specific social circle: your family, your company and your club. For example, inside the 内, family members may drop the title.

In Japanese, soto (外) is the culture’s equivalent of an out-group. As a concept, 外 refers to all the people who are not inside your specific social circle. For example, another company’s employee or team rival.

So why are these concepts important in Japanese keigo? Japan, like many Eastern countries that tend to be collectivist, follows the rough idea that conformity in society is more important, the opposite of the more individualistic views of Western culture.

In other words, being part of a group is an important element in Japan. Japanese speech differs depending on the social context of what you define as your in-group at the moment.

In-group can go as small as your family and span a country. Think of the concept of “us” and “them”. This dynamic concept affects social interactions and is reflected in the Japanese language. So keep in mind that you will not use honorific words when speaking about insiders (people from your social circles) to outsiders.

Japanese Keigo for Beginners

Before you actually dive into keigo, you will probably learn the polite verb forms, otherwise known as teinei (丁寧/ていねい). This consists of the stem of a verb and what is called the ~ます form. For example, the verb “to see”, 見る, becomes 見ます.

Keigo covers both humble form, kenjougo (謙譲語), and polite form, sonkeigo (尊敬語), with various levels of vocabulary and expressions. This written Japanese offers even more complexity.

When you start to have a good command of Japanese, you will realize that politeness in Japanese is of great importance when dealing with elders or working in a professional environment. You will learn to adjust your speech depending on whether you have a certain intimacy with someone or to emphasize the social rank disparity if you are in a higher position.

ご飯を食べます。

Gohan o tabemasu.

映画をみます。

Eiga o mimasu.

But what if you want to show even more respect to someone? After all, humility is a big part of Japanese culture, in work or social life. Take a look at the table below to see three different levels of “politeness”.

| Casual | Formal | Keigo |

|---|---|---|

| お土産をもらった。 Omiyage o moratta | お土産をもらいました。 Omiyage o moraimashita | お土産をいただきました。 Omiyage o itadakimashita. |

One of our students joked that a good rule of thumb is this: the longer the sentence becomes, the more polite and formal it is. We don’t know if it’s entirely true, but that’s the pattern we see.

Now, you’re most likely to use the casual Japanese form with your in-group, with whom you have an equal or casual relationship. This can be your classmates who you know very well, your close friends, siblings, or even parents.

Going up a notch, the formal form is typically used for someone who has more social distance from you: your teachers, coworkers, or strangers.

You use the utmost polite Japanese keigo to someone you deem to sit in a much higher social hierarchy. This demographic falls to people like your managers, boss, and, yes, customers or clients.

But remember the “in-group” and “out-group” concepts again? Japanese people, especially women, have a tendency to use keigo even to a stranger, so don’t be surprised if they talk to you in a very humble and honorific language.

Basic Rules of Keigo

Now that we’ve gotten over who we can use keigo and the concept of uchi and soto, we can deal with the real keigo rules. The Japanese language is actually divided into three groups: the polite style, the humble style, and the honorific style.

When using keigo, some words can be substituted for a more respectful version. For example, the word あした (tomorrow) and ひと (person) will become あす and かた, respectively. This form of speech is called Aratamatta iikata (改まった言い方): formal speech.

The second thing to know is that Japanese honorific prefixes o or go can be added to certain nouns and verbs. The easiest examples is certainly tea, ch,a which becomes “o-cha” and family, 家族, which becomes ご家族.

The adjunction of honorifics after names is also a part of respectful speech. The polite さん, like Tanaka-san (田中さん) becomes Tanaka-sama (田中様).

1. Polite Japanese: Teineigo (丁寧語)

The polite style is the easiest form of keigo, ruled by regular grammar with a structure similar to casual speech. Thus, it is the first form of keigo taught to Japanese language learners. So when you are using です and ます instead of the dictionary form, a considerate and formal tone of Japanese, you are already using keigo.

As a reminder, the copula です comes after nouns, adjectives, and adverbs, generally, at the end of a sentence, while the suffix ます is added at the end of a verb.

| English | Regular | 丁寧語 |

|---|---|---|

| I am going to buy a book. | 本を買いに行く。 Hono kaini iku. | 本を買いに行きます。 Hono kaini ikimasu. |

| The phone is broken. | 携帯(けいたい)が壊(こわ)れた。 Keitaiga kowareta. | 携帯が壊れました。 Keitaiga kowaremashita. |

| What is this? | これは何だ 。 Korewa nan da. | こちらは何ですか。 Kochirawa nandesuka. |

2. Honorific Japanese: Sonkeigo (尊敬語)

This style is to show respect to someone of a higher position, like a superior or a customer, when speaking to them. You should never use 尊敬語 form to refer to yourself. The usage of 尊敬語 is difficult to understand and characterized by lengthy polite sentences. Whereby, common verbs will change to more polite ones, and some will even change into a respectful form.

| English | Regular | Honorofic Form |

|---|---|---|

| Is Mr. Tanaka here? | すみません、田中先生はいますか。 Sumimasen, tanaka-sensei wa imasuka | すみません、田中先生はいらっしゃいますか Sumimasen, tanaka-sensei wa irasshaimasuka |

| How was the interview? | 面接はどうでしたか。 Mensetsu wa dou deshitaka | 面接はいかがでしたか。 Mensetsu wa ikaga deshitaka |

Humble Keigo: 謙譲語

In the table above, you will find the honorific and humble styles’ special set expressions, along with the polite and casual speech forms.

The following humble set-expressions おります, 参ります, いたします, いただきます, もうします, 存じでおります are part of a third category called 丁重語. This courteous form of keigo is not often referred to and is used when your action does not directly involve the listener, but most likely the person you are talking to is someone to whom you want to be very polite.

| English | Regular | 謙譲語 |

|---|---|---|

| I am Sakura. | 私はさくらです。 Watashi wa sakura desu. | 私はさくらと申します。 Watashi wa sakura to moushimasu. |

| The phone is broken. | 携帯(けいたい)が壊(こわ)れた。 Keitaiga kowareta. | 携帯が壊れました。 Keitaiga kowaremashita. |

| I read the book | この本を読みました。 Kono hon o yomimashita. | こちらの本を拝読しました。 Kochira no hon haitokushimashita. |

When referring to yourself, you should be humble. When referring to someone in your inner circle, you should humble them too — because the concept of “in-group” stipulates that they’re part of you too.

The kenjougo (謙譲語) is used to lower your social status when speaking about yourself. It should be used when you are speaking to someone of higher social rank when describing the actions of you or someone in your circle. Like for 尊敬語, the 謙譲語 substitutes verbs with other forms. Nouns may also change: the word 人, previously mentioned, will become 者.

This is particularly important in the Japanese work environment. When you’re speaking directly to your manager, you will probably address them in honorific form — because they’re socially higher than you. Easy, right?

Now, what about when you’re talking to your company’s clients, and suddenly need to mention your managers? To refer to them directly, do you use the humble or honorific form?

The answer is humble form. This is because in that moment, your manager is part of your in-group (uchi) and the client is your soto. An important thing to know is that you “raise” people from your out-group while you lower the people in your in-group, regardless of the individual’s status from the beginning.

Japanese Keigo Conjugation

For both honorific and humble styles, as seen previously, certain verbs have set expressions. For the verbs without such set expressions, they obey keigo conjugations. The first rule is the adjunction of the polite prefix “o” to the stem of the verb.

We often focus on verb constructions and the social relations between a speaker and a listener, but keigo covers more than set expressions and situational examples. In particular, the Japanese language uses honorific prefixes. Most of you might know that the Japanese honorific prefixes お (o) or ご (go) can be added to some nouns and verbs.

When used with a noun, it is preceded by either お (o) or ご (go), but is limited to only nouns which indicate actions (suru verbs). For a verb, erase the ます and add になる.

| English | Honorific Form |

|---|---|

| Verb | お + Verb |

| Noun | お/ご + Noun + になる |

部長はいつ海外からお戻りになりますか。

課長はお変えになりました。

You can essentially add お (o) or ご (go) to any nouns to transform them into honorific form, but be careful. Adding too many prefixes will make your sentences sound awkward — we don’t want you trying too hard, and there are other ways to talk in keigo without putting お before every object.

However, you’ll most likely encounter these words without realizing that they are nouns with honorific prefixes.

| English | Honorific Japanese | Romaji |

|---|---|---|

| Tea | お茶 | Ocha |

| Water | お水 | Omizu |

| Alcohol | お酒 | Osake |

| Meal | ご飯 | Gohan |

| Order | ご注文 | Gochuumon |

| Sweets | お菓子 | Okashi |

| Time | お時間 | Ojikan |

For the humble style, the construction of the verb will be as follows: お/ご + stem of the verb + する. You have certainly heard it before in お+願い+します(“please”).

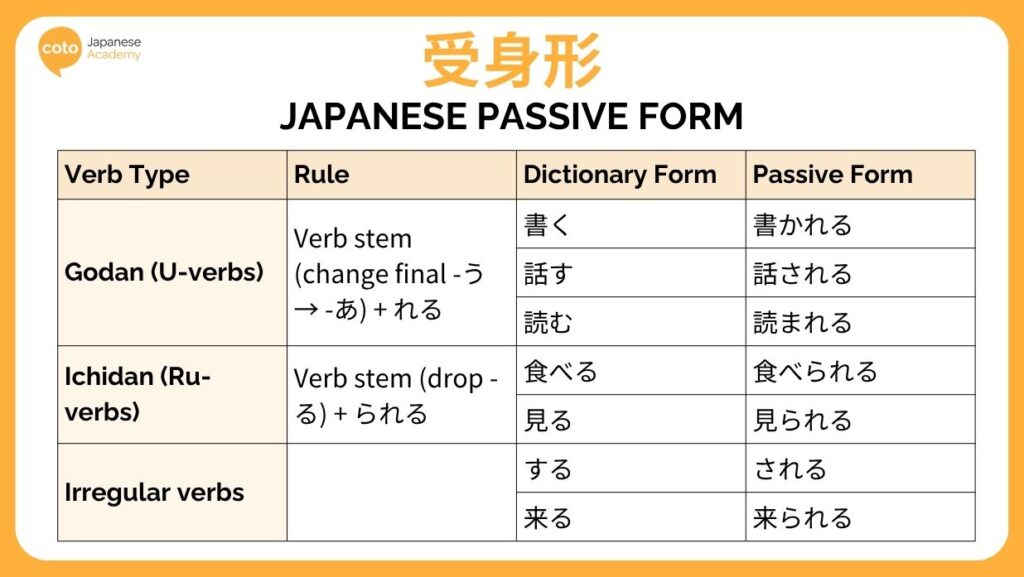

The honorific style can also be expressed with what is called the “easy keigo,” with verbs used in the passive form れる or られる. Although said to be easier, this form of keigo can be confused with the passive voice and should be used with care.

29 Useful Japanese Keigo Phrases for Work

The first step is understanding that some kanji readings and some words are different depending on whether you are casual or polite. The easiest example is the word “tomorrow”. You’ll learn 明日 is read あした, but as you progress in your Japanese studies, you’ll quickly encounter the reading あす.

| English | Casual Japanese | Keigo words for work |

|---|---|---|

| Tomorrow | 明日(あした) | 明日(あす) |

| After tomorrow | 明後日(あさって) | 明後日(みょうごにち) |

| Last night | 昨日の夜 | 昨夜 (さくや) |

| Tomorrow morning | 明日の朝 | 明朝 (みょうちょう) |

| From tomorrow | 明日以降 | 後日 (ごじつ) |

| This year | 今年 | 本年 (ほんねん) |

| The other day | この間 | 先日 (せんじつ) |

| On that day | その日 | 当日 (とうじつ) |

| Last year | : 去年(きょねん) | 去年(さくねん) |

| Year before last | 一昨年(おととし) | 一昨年(いっさくねん) |

| Soon, shortly | もうすぐ | まもなく |

| Now | いま | ただいま |

| Earlier | 前に | 以前 (いぜん) |

| Later | あとで | 後ほど (あとほど) |

| Immediately | すぐに | さっそく |

| This time, now | 今度 | このたび |

| Just now | さっき | 先ほど (さきほど) |

| Where | どこ | どちら |

| This way | こっち | こちら |

| That way | あっち | あちら |

| Over there | そっち | そちら |

| Which one | どっち | どちら |

| Just a minute | ちょっと | 少々 (しょうしょう) |

| Very, terribly | とても | 大変 (たいへん) |

| Very, greatly | すごく | 非常に (ひじょうに) |

| How many, how much | どのくらい | いかほど |

| A few, a little: | 少し | 些少(さしょう) |

| Considerable | 多い | 多大 (ただい) |

| About, approximately | ~ぐらい | ~ほど |

When Should I Use Japanese Keigo?

Well, respectful language should be used toward older people, toward distinguished people, and in the workplace. Of course, exceptions exist, and that is why keigo is as difficult for native speakers as for learners.

The respectful language can be strictly applied in one company or more loosely in another. Foreigners often get slack from the Japanese as they do not expect a non-native to master this speech.

The difficulty also resides in the unknown: a gathering of people you do not know, and here you are at a loss, not knowing who is eminent, who is your age, and who is younger. In some contexts, casual speech is preferred as an icebreaker while Keigo would be considered too distant.

Speaking Keigo As a Foreigner in Japan

While native speakers are expected to use proper keigo (and if they do not, they are seen as unprofessional and will be frowned upon), the same is not always true for non-native speakers. Foreigners are often forgiven for their misuse of keigo and are excused for not having a good command of that high level of Japanese.

That being said, you should do your best to try and learn Japanese keigo. And the best way to master the Japanese honorific is to learn slowly but surely all the ins and outs of respectful speech.

Learn business Japanese with Coto Academy!

Want to thrive in your career in Japan or make a successful job switch? As Japan becomes increasingly international, mastering Japanese is more important than ever to boost your professional opportunities.

One of the best ways to advance is by learning proper business Japanese at top language schools like Coto Academy. Our bespoke Business Japanese classes cover essential workplace etiquette, keigo (honorific language), and professional manners tailored for the Japanese work environment.

What sets us apart? We keep classes small — just 8 students per group — so you get plenty of speaking practice and personalized attention. Most of our students are expats or Tokyo residents with work experience in Japan, making it a great opportunity to build your network and connect with a supportive community.

Interested? Fill out the form below for a free level check! You can also schedule a free consultation or chat with our team to find the best learning path tailored to your goals.

FAQ

What is Keigo?

Keigo is the Japanese system of honorific language used to show respect, politeness, and humility depending on the social context.

Why is Keigo important in Japanese?

It reflects respect for hierarchy and social relationships. Using keigo correctly is essential in formal situations like work, customer service, and meeting new people.

What are the main types of Keigo?

- Teineigo (丁寧語): Polite language using -masu/-desu endings.

- Sonkeigo (尊敬語): Respectful language for elevating others.

- Kenjōgo (謙譲語): Humble language to lower yourself or your in-group.

When should I use Sonkeigo?

When referring to the actions of someone above you in status, like a boss, customer, or teacher.

When should I use Kenjougo?

When talking about your own actions in a formal setting, especially in service roles or business.

Is Teineigo enough for daily conversations?

Yes! Teineigo is perfectly fine for general polite conversations, especially if you’re a learner or in casual-professional settings.

Do native speakers always use Keigo perfectly?

Not always. Even native speakers adjust based on context and may sometimes mix forms casually.

How can I practice Keigo?

Listen to real conversations (like in dramas or customer service), mimic phrases, and study common verb transformations for each keigo type.

Is Keigo only for business?

No—while it’s crucial in business, it’s also used in schools, public services, formal events, and when meeting someone for the first time.

Want to work in Japan? You might like related content like:

- Japanese Work Culture: How is it Different from the West?

- How to Write a Japanese Resume (Rirekisho): Free PDF Template

- How to Get a Job in Japan as a Foreigner

- Common Japanese Job Interview Questions to Know

- How to Introduce Yourself in Japanese

- How to Quit Your Job in Japan

- Jobs You Can Do in Japan Besides English Teaching

- How to Exchange Business Cards in Japan: Meishi Koukan