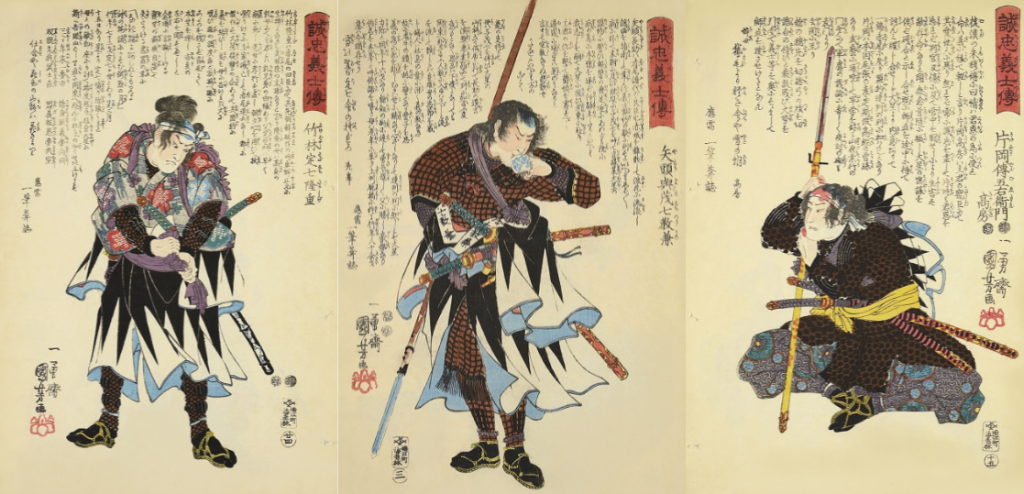

Samurai was once a term to describe aristocratic warriors known as “bushi”. They’re members of a powerful military caste that rose to prominence in the 12th century, when Japan was on its way to military dictatorship (shogunate). The warriors dominated Japanese politics, economy, and society up until the nineteenth century. They maintained their wealth and position not just through their brutality and martial prowess, but through profound cultural influence and financial literacy.

Now, you can’t talk about Japanese history without mentioning samurai. Beyond katana (刀, かたな) and undeniable loyalty, samurai heritage and philosophy helped shape modern Japanese society.

The samurai’s code of conduct bushido, which translates to “the way of the warrior”, is strongly based on Confucianism. Bushido stresses loyalty, morality, discipline, and ethical behavior and gained popularity during the late Meiji Era. s

Jump to:

- The Birth of Samurai

- The Rise of Samurai

- Bushido and Zen: The Samurai Culture and Philosophy

- Meiji Restoration and The End of the Samurai Period

- Things Everybody Gets Wrong About Samurai

- Samurai in Modern Japan

- How to Appreciate Samurai Culture Today

The Birth of Samurai

The word “samurai” translates to “those who serve”. The word “bushi”, which is often synonymous with samurai, lacks the connotation of service to a master.

Traces of the first samurai can be found during the Heian Period (794-1185). They were initially armed supporters hired by wealthy landowners for protection after they left the imperial court and grew independent to seek their own fortune.

Political dynamics in Japan saw a gradual shift in the mid-twelfth century, when the largest influence went from the emperor to aristocrats and powerful landowning clans. Through protective agreements and political marriages, they accumulated political power, eventually surpassing the traditional aristocracy.

Also check out: Emperor’s Birthday (天皇誕生日): Celebrating Centuries of History

Two dominating clans — Minamoto and Taira — challenged the government and battled each other (known as the Gempei War). Minamoto Yoshitsune, a military commander of the Minamoto, brought his clan to victory against the Taira.

They set up a new military government in 1192, led by the shogun or supreme military commander under the central government of Kamakura. The establishment of the Kamakura Shogunate put real political power in Japan to the samurai. The samurai would rule over Japan for most of the next 700 years.

The Rise of Samurai

Minamoto Yoritomo, the half-brother of Yoshitsune, defined and permitted the samurai’s privileged status. It was during this period when the sword, or katana, hold significance in the samurai culture: a man’s honor resided in his sword and the art of its craftsmanship.

From then, Japan entered a chaotic era of political unrest. States were warring against each other, and in the 13th century, the Kamakura Shogunate fell after two Mongol invasions and a rebellion from the Ashikaga. For the next two centuries, Japan was in a near-constant state of conflict between its feuding territorial clans.

Lacking a strong central authority, local lords and their samurai stepped to a greater extent to maintain law and order. The samurai of the Kamakura period developed a disciplined culture, holding great pride in their military skills and stoicism.

Bushido and Zen: The Samurai Culture and Philosophy

During the Muromachi period (1392–1573), a lot of samurai became devoted patrons of Zen Buddhism, which was introduced in China. Despite their brutality in nature, leaders became highly cultivated individuals.

Zen Buddhism’s belief that salvation comes from within became the philosophical base of the samurai’s code of behavior. Under Zen’s growing influence and in the late medieval period, the samurai culture also developed a lot of Japanese arts that trickled down to the present-day: tea ceremony and flower arranging (ikebana; 生け花). A number of shoguns became avid art collectors and supporters of the Noh and Kyogen theatre. They sponsor the construction of temples and gardens in Kyoto.

It was during the Edo period (1615–1868) when samurai’s moral code concerning samurai attitudes, behavior and lifestyle was formalized into bushido. Previously, the feudal samurai class followed this unwritten code of conduct. The samurai became the highest-ranking social caste and made up the ruling military class.

Bushido: The Ancient Code of the Samurai Warrior

The bushido focuses on loyalty to a warrior’s lord and honor above your own life. Though this ancient code varied depending on the influences of Buddhists and Confucians, bushido followed a constant emphasis on military skills and fearlessness. Ritual suicide — the act of stabbing yourself in the abdomen with a short sword for a slow and agonizing death —was considered an honorable alternative to defeat.

Bushido also emphasized frugality, kindness, honesty, and care for one’s family members, particularly one’s elders.

Bushido was officially compiled in the late 17th century by scholar Yamago Soko. At this time, samurai were no longer active military clans. Rather, they acted as advisors and guides.

Meiji Restoration and The End of the Samurai Period

In the 15th and 16th centuries, independent states in Japan pitted one another, making the samurai high in demand. Ninja or shinobi, agents or mercenaries in feudal Japan, specializing in espionage and unconventional warfare, were more frequently hired.

In the Edo period, samurai topped the social caste system in Japan, followed by farmers, artisans and merchants. Only they have the right to carry swords. This privilege earned them the nickname “two-sword man”; they would carry a short sword (either the Wakizashi, or the Tanto) and a long sword.

However, samurai were forced to live in castle towns, and they made their living on a fixed stipend from their feudal lords (daimyo). The wealth of a samurai in feudal Japan was measured in terms of koku. One koku amounted to a year’s worth of rice, which was around 180 liters. Samurai (浪人, “drifter” or “wanderer”) without a lord or master was called ronin.

The period of war, called Sengoku-Jidai, eventually ended in 1615. With Japan now unified, a long period of peace stretched for 250 years. The samurai’s governing responsibility moved from using military brute to civil means. They were trained equally in arms and “polite” learning according to the principles of Confucianism. With the importance of martial skills now less significant, a lot of samurai were forced to become bureaucrats, traders, teachers or artists — while still being able to carry their two swords.

Japan’s feudal era eventually came to an end in 1868 during the Meiji Restoration. By then, Japan had undergone a massive revitalization, including expansion of the economy and cities. The daimyos were summoned by the Emperor, only to be declared their all their lands must be returned to the government.

Their debts and payments of samurai stipends were taxed heavily or turned into bonds which resulted in a large loss of wealth among former samurai. When these stipends declined, many lower-level samurai were unable to improve their situation. Despite high social rank, samurai families suffered impoverishment.

The samurai class was abolished a few years afterward, but many would become leaders in all areas of modern Japanese society.

Things Everybody Gets Wrong About Samurai

A lot of things we know about samurai aren’t wrong — but there’s so much to being a samurai than being a skilled swordsman and honorable, loyal warrior.

a. Only Japanese people were samurai

On exceptional occasions, non-Japanese people were given the title of samurai. William Adams was the first Westerner to be named a samurai and gifted two swords, followed by a Jan Joosten van Lodensteijn from Dutch, French soldier Eugene Collache and Prussian military Instructor (Edward Schnell). Yasuke was Japan’s first (and allegedly only) African man to be made a samurai.

b. Only men could become samurai

Onna-musha (女武芸者) are female warriors who fought alongside samurai men. They were members of the bushi and were trained to use weapons.

c. Samurai were elite and exclusive warriors

There was fairly a lot of samurai for a higher clan. In the 16th century, samurai accounted for 10% of the whole population of Japan. At their peak, there were 2 million Japanese.

d. Samurai only use swords as a weapon

Samura uses a range of weapons like arrows, spears, and bows (they were actually very good bowmen). They started using guns after it was introduced in Europe in the mid-15th century. Only they were allowed to own firearms until the middle of the 19th century.

e. Samurai were noble warriors

The notion that they were all chivalrous warriors isn’t entirely accurate. Initially, the honor came from victory — and nowhere else. They were also known to collect severed heads of their victims. Promises and truces were frequently violated, villages were burned, and generals would switch sides mid-battle.

Later, samurai would become infamous for beheading total strangers on the roadside. The reason? Just to test if their sword is sharp — an act is known as tsujigiri (“cutting down at the crossroads”).

Samurai in Modern Japan

The samurai spirit permeates the lives of modern Japanese people. The reputation of samurai has continued to flourish today thanks to comic books, computer games, and other media.

In February 2021, Netflix released its documentary show Age of Samurai: Battle of Japan. In the span of six episodes, the series documented the warlord Oda Nobunaga, the final phase of the Sengoku period (The Age of Warring States) and the life of a powerful daimyo who clash to unify Japan.

Samurai has always been a buzzword, but it gained more recognition since the show hit the giant streaming service

How to Appreciate Samurai Culture Today

The samurai warriors do not exist today, but the samurai cultural legacy is still preserved. Now, you can find samurai attractions across Japan: castles, museums, samurai residences, and tours. Get a glimpse into the life of a samurai through these attractions.

Experience the culture and history of samurai through:

a. Samurai museum

If you want to see Japanese swords and armors, head to one (of the many) samurai museums. A lot of history museums in Japan only display a collection of samurai artifacts, but you’ll easily find museums that specifically show exclusive relics.

- Samurai & Ninja Museum in Kyoto

- Samurai Museum in Kabukicho, Tokyo (temporarily closed due to COVID-19)

Sword Museum in Tokyo features one of the largest public sword collections in the country. The Maeda and Honda Museums in Kanazawa feature relics of the two most prominent samurai families in the region.

b. Samurai residence

Experience the life of a samurai by staying overnight at their former residence.

- In Miyagi Prefecture, you can stay at a renovated samurai house, Murata Buke no Yado.

- In Ojika Island, Nagasaki Prefecture, you can rent a majestic Japanese mansion that was once a samurai residence.

- Near Kumamoto Castle, a former Hosokawa Residence serves as the home of the ruling Hosokawa Clan.

c. Samurai Theme Parks

Samurai may not exist anymore, but you can try to “transport back in time” by visiting recreated towns. Samurai theme parks offer live shows, museums, shops, and restaurants; staff are decked in Japanese feudal-era costumes.

Nikko Edomura in Tochigi Prefecture has a recreated Edo-period town, complete with samurai, ninja and townspeople.

Toei Kyoto Studio Park is the only theme park — although it’s more of a film set — in Japan where you can observe the filming of period dramas (jidaigeki films). You’ll find themed streets, a traditional courthouse and a replica of the old Nihonbashi Bridge.

Located in Hokkaido, Noboribetsu Date Jidaimura offers attractions, shows and a town with townspeople.

d. Samurai Town

Today, you can find a few samurai districts that still maintain their historic allure and welcome tourists.

- Kakunodate, well known for its Samurai District, was formerly a castle town in the Semboku region. Six of the remaining samurai houses, or bukeyashiki, are open to the public.

- Kitsuki is located on the southern side of the Kunisaki Peninsula in Oita Prefecture. The city has two samurai districts on hills north and south.

- Nagamachi in Kanazawa preserves a few lanes, museums and samurai residences that are open to the public.

Love what you’re reading? Coto recommends these related articles:

- Setsubun: Ultimate Guide to Welcoming a New Season in Japan

- Obon: A Japanese Tradition Honoring The Ancestors’ Spirits

- New Year’s Day (元日): A Time for Tradition

- Culture Day: The Holiday that Commemorates Peace

Love Japanese culture? Start learning the language behind it

Whether you’re drawn to samurai history, anime, or traditional arts, understanding Japanese opens the door to truly appreciating Japan on a deeper level.

At Coto Academy, we offer flexible and engaging Japanese lessons tailored to your pace, from complete beginners to advanced speakers. Join our intensive Japanese course or part-time intensive courses!

All image courtesy of Canva.

FAQ

Who were the samurai?

The samurai were a warrior class in feudal Japan who served powerful landowners (daimyō) and followed a strict code of honor known as bushido (“the way of the warrior”). They played a major role in Japanese history for over 700 years, from the late 12th century until the Meiji Restoration in the 19th century.

What was bushido?

Bushidō was the samurai code of ethics, emphasizing loyalty, discipline, courage, and honor, even to the point of death. It shaped not only the lives of warriors but also Japanese philosophy and culture.

Are there samurai today?

While the official class no longer exists, many families trace their lineage back to samurai ancestry. The spirit of bushidō also continues to influence modern Japanese ethics, sports, and even business culture.

While the katana is the most iconic samurai weapon, samurai also used bows, spears (yari), and later, even guns. Their role evolved from archers on horseback to swordsmen and military officials.

What happened to the samurai?

The samurai class was officially abolished during the Meiji Restoration in the late 1800s, when Japan modernized its military and government. However, their legacy still lives on in Japanese martial arts, culture, and values.