Hiragana, katakana, and kanji make up the Japanese writing system. When you start learning Japanese, figuring out how to read and write can feel overwhelming; after all, Japanese is completely different from the Roman alphabet! You then learn that there are three different writing systems used all at once. How is that even possible? Not to worry – these systems are simpler than you might expect! Each one has unique, defining characteristics and uses; once you learn more about these, reading and writing Japanese will be a breeze!

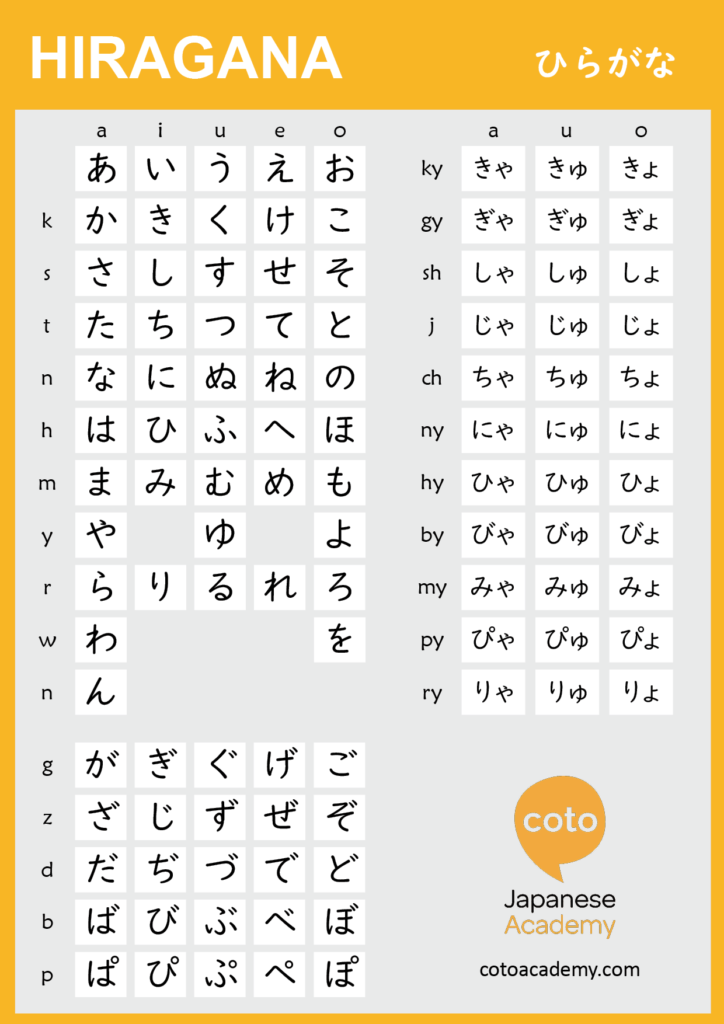

We’ve covered smaller articles for each Japanese writing system. Don’t forget to check out our downloadable hiragana chart and quiz for a more detailed guide and resource recommendation.

Origins of the Japanese Alphabet

Do you know about the history and the origin of hiragana and katakana? Originally, the Japanese ancestors did not have a writing system. Around the fifth century, they started using kanji, ideograms that were adopted from China and Korea. They only used the phonetic reading of the kanji, regardless of their meaning. At that time, the ideograms were called manyogana (万葉仮名).

However, kanji’s characters are composed of many strokes. They take longer to write, as you have noticed by now! Due to their difficulty, those ideograms were slowly simplified into kana alphabets, namely hiragana and katakana. They are called syllabograms, as each character corresponds to one sound in the Japanese language. According to historians, the change was initiated by Buddhist priests who thought kanji could not accurately represent the Japanese language and that a phonetic alphabet would be better.

Examples of Change

On the left is the manyogana, and on the right are simplified hiragana and katakana forms.

- 安 →あ 阿 → ア (a)

- 以 →い 伊 → イ(i)

- 宇 →う、ウ(u)

- 衣 →え 江 → エ(e)

- 於 →お、オ(o)

This change is thought to have occurred between the eighth and ninth centuries. Hiragana can be considered a simplified calligraphy form of the kanji’s strokes. On the other hand, katakana is taken from a single element of a kanji. In some cases, the Hiragana and Katakana are created from different ideograms.

Some hiragana and Katakana express the same sound and have similar shapes, such as り and リ. However, some can be dissimilar, such as あ and ア. Hiragana is said to be cursive, while katakana is more angular. Do take note that one sound can have more than one hiragana. In 1900, the two kana scripts, hiragana and katakana, were codified. This led to the clear establishment of rules for the Japanese system in 1946.

Japanese Writing System #1: Hiragana

Whenever you just start out learning Japanese, hiragana is usually the first writing system you learn. Hiragana is technically a syllabary or a way of writing where symbols represent whole syllables (such as “ba” and “to”) instead of individual sounds (such as “b” or “t”)5. This is because all Japanese words are made up of these small syllables, so there’s no need to write out individual sounds!

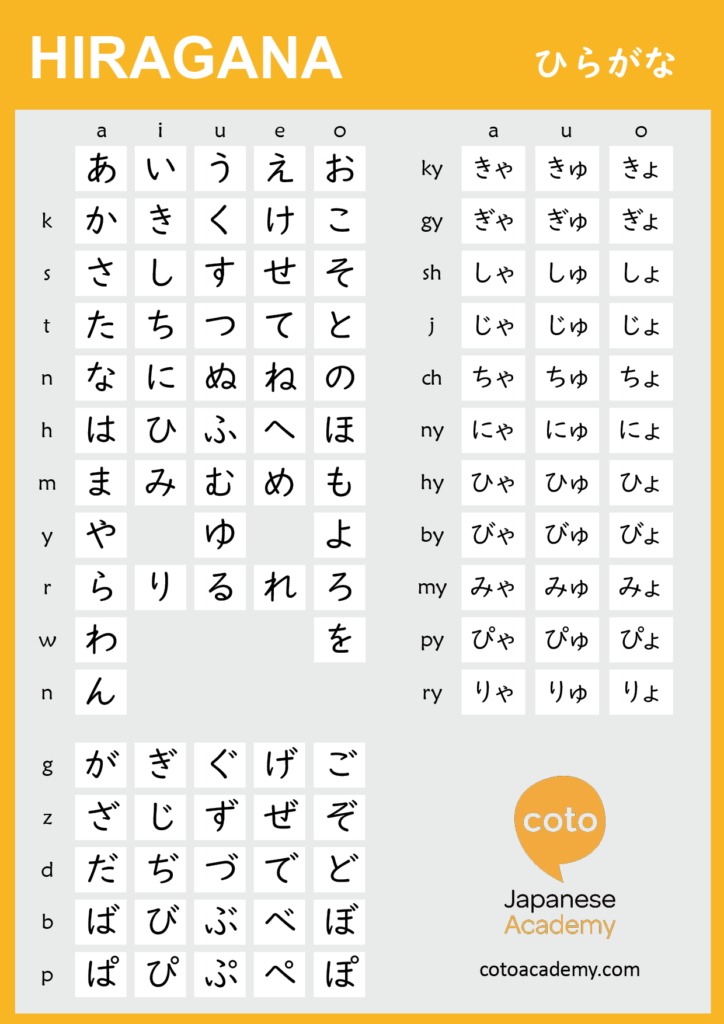

In Japanese, there are 46 basic syllables:

- The basic vowels: a, i, u, e, o.

- The k-line: ka, ki, ku, ke, ko.

- The s-line: sa, shi, su, se, so. (Notice that the “si” sound is instead replaced by “shi.”)

- The t-line: ta, chi, tsu, te, to. (Notice that the “ti” and “tu” sounds are instead pronounced closer to “chi” and “tsu.”)

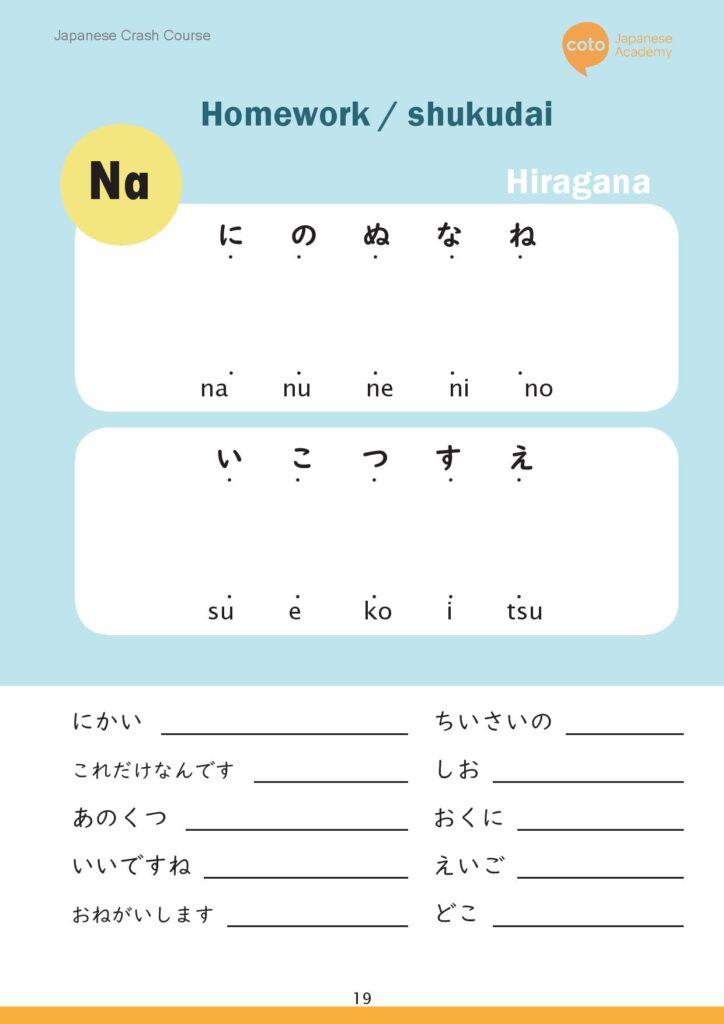

- The n-line: na, ni, nu, ne, no.

- The h-line: ha, hi, fu, he, ho. (Notice that the “hu” sound is actually said as “fu.”)

- The m-line: ma, mi, mu, me, mo.

- The y-line: ya, yu, yo.

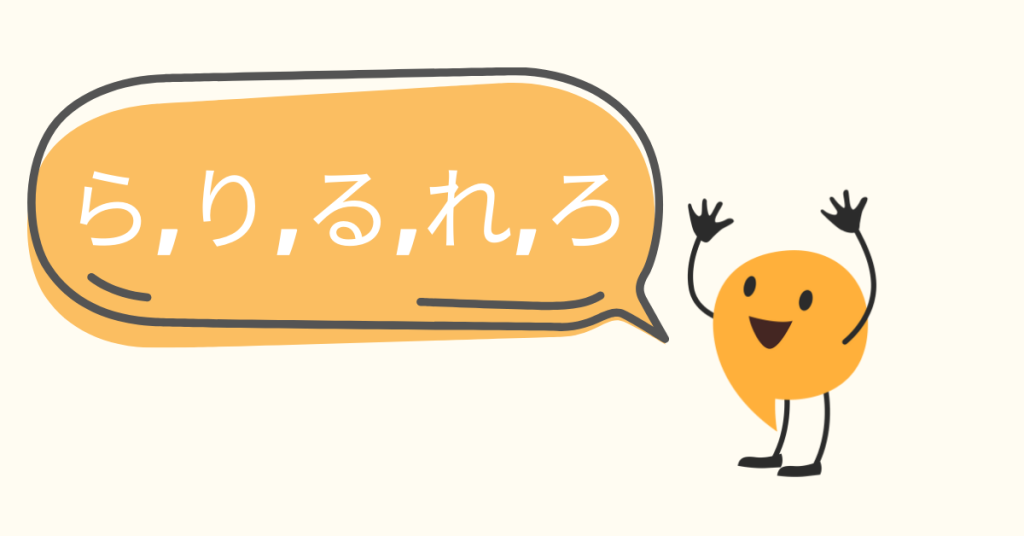

- The r-line: ra, ri, ru, re, ro.

- Wa, o/wo, and n. (These sounds are unique, so they are generally placed together. The “o/wo” symbol can be pronounced either way and “n” is considered a whole syllable in Japanese.)

There are also 23 additional syllables in Japanese; these are formed with additional marks that we’ll cover in a minute.

- The g-line: ga, gi, gu, ge, go.

- the z-line: za, ji, zu, ze, zo. (Notice that “ji” is used instead of “zi.”)

- The d-line: da, ji, zu, de, do. (“ji” and “zu” are pronounced the same way as in the z-line but have different uses.)

- The b-line: ba, be, bu, be, bo.

- the p-line: pa, pi, pu, pe, po.

Writing Hiragana

So, now that we’ve covered the basic sounds, let’s see how these syllables are written down in hiragana:

Hiragana is generally round in shape, with lots of curves and bends. This characteristic is a key way to tell what symbols are hiragana! You can also combine a consonant with a / ya / yu / yo / sound by attaching a small 「や」、「ゆ」、or 「よ」 to the / i / vowel character of each consonant.

Now, let’s take a look at those 23 additional sounds:

- the g-line: が(ga), ぎ(gi), ぐ(gu), げ(ge), ご(go).

- the z-line: ざ(za), じ(ji), ず(zu), ぜ(ze), ぞ(zo).

- the d-line: だ(da), ぢ(ji), づ(zu), で(de), ど(do).

- the b-line: ば(ba), べ(be), ぶ(bu), べ(be), ぼ(bo).

- the p-line: ぱ(pa), ぴ(pi), ぷ(pu), ぺ(pe), ぽ(po).

Did you notice something about the above sounds? The hiragana for the g-line is identical to the k-line, and the same goes for the z-line and s-line, the t-line and the d-line, the h-line and the b- and p-lines! The only difference is the addition of diacritical marks; these marks go to the upper right of the hiragana and can be either two short diagonal marks (called a dakuten) or a small circle (called the handakuten). This is pretty nice, as you don’t have to memorize even more symbols!

There are also contracted sounds in Japanese. These sounds are basically combinations of sounds ending in “-i” and the y-line and are considered one syllable as well. All you have to do for these is add a small y-line hiragana after the main hiragana! (Notice that not all of these syllables keep the “y” sound.)

- the k-line: きゃ(kya), きゅ(kyu), きょ(kyo)

- the s-line: しゃ(sha), しゅ(shu), しょ (sho)

- the t-line: ちゃ(cha), ちゅ(chu), ちょ(cho)

- the n-line: にゃ(nya), にゅ(nyu), にょ(nyo)

- the h-line: ひゃ(hya), ひゅ(hyu), ひょ(hyo)

- the m-line: みゃ(mya), みゅ(my) みょ(myo)

- the r-line: りゃ(rya), りゅ(ryu), りょ(ryo)

- the g-line: ぎゃ(gya), ぎゅ(gyu), ぎょ(gyo)

- the z-line: じゃ(ja), じゅ(ju), じょ(jo)

- the b-line: びゃ(bya), びゅ(byu), びょ(byo)

- the p-line: ぴゃ(pya), ぴゅ(pyu), ぴょ(pyo)

So, that is the basics of how hiragana is written. However, there are also double consonants and long vowels, which are written with variations in hiragana (and katakana). We recommend checking out our full-length article about double consonants and long vowels to learn more about those!

How to Use Hiragana

Hiragana can be used for many things; it’s like the all-rounder of writing Japanese, and it represents all the syllables of the Japanese language! Hiragana is used when writing verb endings, particles, grammar words (such as conjunctions), and many native Japanese words, as well as for words that do not have a corresponding kanji character. Hiragana is also used in furigana; this is when hiragana is written in a small font above kanji for those who don’t know the kanji’s reading.

Long Vowels and Double Consonants in Hiragana

In Japanese hiragana, double consonants are represented by adding a small “tsu” character (っ) before the consonant that is doubled. For example, the word “katta” (勝った), meaning “won”, would be written as かった, with a small “tsu” between the two “t” characters.

Long vowels in hiragana are done by extending a consonant or vowel with another vowel, depending on the vowel in accordance with the following chart.

For example, the word “ookii” (大きい), meaning “big”, would be written as おおきい.

| Vowel Sound | Extended by | Example |

|---|---|---|

| a | あ | おばあさん |

| i, e | い | おおきい、きれい |

| u, o | う | こうこう、くうき |

Example

Let’s start off with a simple sentence – “My pet’s name is Bob.” (What a funny name for a pet!) In Hiragana, this looks like this:

わたしの ぺっと の なまえ は ぼぶ です。

Watashi no petto no namae wa bobu desu.

So, we can write a whole Japanese sentence just using hiragana! This is how most people (including native speakers) start off reading and writing Japanese. Of course, as you learn about katakana and kanji, some of these words will be replaced. However, you will see that the particles (の [no] and は [wa]) and the native verb です(desu) will remain the same, as these are some of the things that specifically use hiragana!

Now that you’ve learned the basics, it’s time for practice! Head on over to our list of practice sheets, apps, and quizzes to make sure you’ve got a solid understanding of hiragana!

Tips for Writing in Japanese

1. There are no spaces in the Japanese writing system

Japanese is written with no spaces, so a combination of hiragana, kanji, and katakana helps distinguish words within a sentence. As you improve your Japanese writing and reading skills, you’ll start to feel that reading kanji is often easier than reading a sentence that consists solely of hiragana.

2. Be careful of hiragana characters that sound and look similar

Pay more attention when pronouncing “tsu” and “su”. Beginner-level students also have a hard time discerning ro (ろ), re (れ), ru (る) — and nu (ぬ) and me (め) because they look similar.

3. Correct stroke order and direction are important

Writing hiragana with the correct stroke order and direction will help you intuitively know how to write new characters, and it has a big effect on how readable it ends up looking.

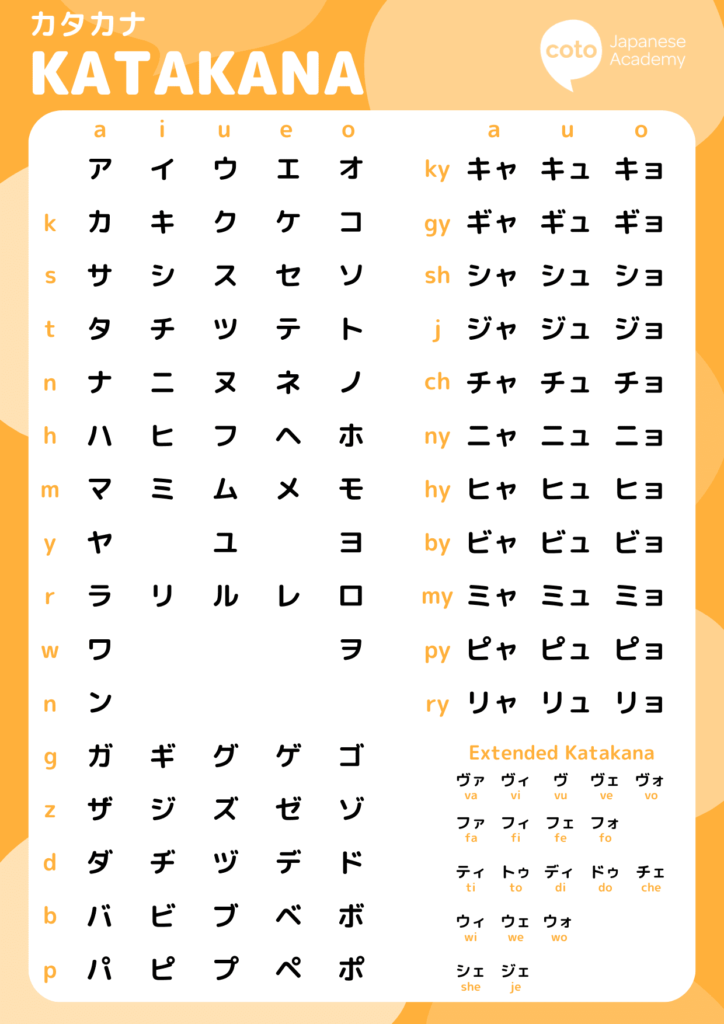

Japanese Writing System #2: Katakana

After hiragana, it’s a good idea to learn katakana next; katakana works the exact same way that hiragana does, just using different characters; some katakana symbols even look similar to their hiragana counterparts! In fact, hiragana and katakana are often collectively referred to as kana, since they are so similar!

Writing Katakana

| the basic vowels | ア(a), イ(i), ウ(u), エ(e), オ(o) |

| the k-line | カ (ka), キ(ki), ク(ku), ケ(ke), コ(ko) |

| the s-line | サ(sa), シ(shi), ス(su), セ(se), ソ(so) |

| the t-line | タ(ta), チ(chi),ツ(tsu), テ(te), ト(to) |

| the h-line | ハ(ha), ヒ(hi), フ(fu), へ(he), ホ(ho) |

| the n-line | ナ(na), ニ(ni), ヌ(nu), ネ(ne), ノ(no) |

| the m-line | マ(ma), ミ(mi), ム(mu), メ(me), モ(mo) |

| the y-line | ヤ(ya), ユ(yu), ヨ(yo) |

| the r-line | ラ(ra), リ(ri), ル(ru), レ(re), ロ(ro). |

| ワ(wa), ヲ(o/wo), and ン(n). |

Now, let’s take a look at those 23 additional sounds:

- the g-line: ガ(ga), ギ(gi), グ(gu), ゲ(ge), ゴ(go).

- the z-line: ザ(za), ジ(ji), ズ(zu), ゼ(ze), ゾ(zo).

- the d-line: ダ(da), ヂ(ji), ヅ(zu), デ(de), ド(do).

- the b-line: バ(ba), ビ(bi), ブ(bu), べ(be), ボ(bo).

- the p-line: パ(pa), ピ(pi), プ(pu), ぺ(pe), ポ(po).

The contracted sounds are also formed in the same way as in hiragana. However, katakana has additional combinations with small vowel letters to transcribe foreign sounds that did not originally exist in Japanese. These are generally easy to pronounce, as you simply combine the consonant of the main katakana symbol with the vowel of the smaller one.

Examples of this include the フェ (fe) in カフェ (kafe), the ティ (ti) in パーティー (paatii), and the ウィ (wi) in ハロウィーン (harowiin)!

You can see that katakana is simpler and has more straight lines than hiragana; this is one major way to tell them apart!

If you want to learn more about katakana, check out our article below and get a free, downloadable PDF of our chart!

Read More: What is Katakana? Free Katakana Chart and Learning Guide

How and When to Use Katakana

Another way to tell them apart is by their usage. Katakana is used for foreign loanwords or words from different languages. ハンバーガー (hanbaagaa, hamburger) and アルバイト (arubaito, part-time job) are examples of Japanese words taken from English and German, respectively. Many non-Japanese names are spelled using katakana as well!

Katakana is also often used for onomatopoeic words, which are words that imitate sounds, such as “pikapika” (sparkling), “gacha” (clacking sound), or “wanwan” (dog’s bark).

Katakana can also be used to emphasize words, similar to how words might be italicized or bolded in English. You can usually see this more in signs or advertisements, like メガネ, megane (glasses) or ラーメン (raamen, glasses).

Long Vowels and Double Consonants in Katakana

Long vowels in katakana are so much simpler than hiragana. All long vowel sounds are denoted by a simple dash: ー.

For example, the word “アート” (aato), meaning “art”, has a long “a” sound represented by the horizontal line over the “a” character.

Double consonants in Katakana are represented using a small “tsu” character (ッ) just like in Hiragana. For example, the word “バッグ” (baggu), meaning “bag”, has a double “g” sound represented by the small “tsu” character.

Example of Katakana

Remember the pet with the funny name? Let’s take another look at that sentence, this time adding in katakana – try to guess where the katakana will be!

わたしのペットのなまえは ボブ です。

Watashi no petto no namae wa bobu desu.

Did you guess petto and bobu? Both of these words are English loanwords and names, so they would be written in katakana. Including katakana when writing Japanese is also a great way to make the words easier to distinguish from each other; writing in all hiragana could make it hard to tell words apart, since Japanese doesn’t normally use spaces!

Difference between Hiragana and Katakana

Why are there 2 syllabic Japanese scripts? In the event that the difference is stylistic, you will learn that hiragana is used to write native Japanese words. Those words will have no kanji representation, and the ideogram will be too ancient or too difficult to write. This kana script is also the one used to write grammatical elements such as particles: を (wo)、に (ni)、へ (he;e)、が (ga)、は (ha).

On the contrary, the Japanese use katakana to write words of foreign origin and foreign names. If you like to read manga in Japanese, you will certainly notice that katakana is also used to represent onomatopoeia and emphasis.

Have you heard of the word “furigana”? Furigana are hiragana and katakana characters written in small forms above kanji in order to show the pronunciation. Furigana is used in kids’ books and Japanese language textbooks for learners, in order to teach the reading of unknown kanji.

Japanese Writing System #3: Kanji

Kanji is usually the last system to be learned, even for native Japanese speakers! Kanji are Chinese characters and were Japan’s first writing system. They were first introduced to Japan over 1,500 years ago; hiragana and katakana actually evolved from these symbols!

Kanji are complex characters that represent words or ideas, and they form the backbone of the Japanese writing system. In fact, it is estimated that there are over 50,000 kanji characters, although only a fraction of those are commonly used.

Reading Kanji

Kanji is different from hiragana and katakana in that there are multiple ways to pronounce a single character. This is because there is a Chinese way to read a character (called the on-yomi) and a Japanese way (the kun-yomi). The on-yomi was the original way, but when kanji started to be used to write native Japanese words, new pronunciations were added1. So, if you see a character pronounced one way in one word but differently in another, this is why!

Writing Kanji

Radicals

All kanji are made up of one or more radicals. A radical is simply a small symbol that, either by itself or when combined with other symbols, makes up a complete kanji character. Take, for instance, the radical 一. By itself, this is the complete kanji for ichi (one). But, it can be added with the radical亅to form the kanji 丁! There are 214 total radicals used in 13 different positions when forming kanji, though some radicals and positions are used more frequently than others. If you think of all kanji as being made up of these smaller radicals, then they will be easier to learn!

There are roughly four main types of kanji, based on how and why the radicals are arranged1:

1. Pictograms

These kanji originally came from pictures, simply drawing the object itself to represent it in writing1. It’s like writing “😊” to represent “smiley face” – just like emojis today! Take a look at 山 (yama, mountain) for example; doesn’t the character 山 remind you of how a mountain looks, with a pointy peak at the top?

2. Simple Ideograms

These kanji originally used lines and dots to “represent numbers or abstract concepts.1” So, instead of drawing an object, you would try to visually represent the idea you wanted to convey. Take “up” and “down” for instance; drawing a dot above a line could represent “up” while a dot below a line would signify “down.” This is where 上 (ue, up) and 下 (shita, down) came from1!

3. Compound Ideograms

Basically, these are kanji formed by combining two or more simpler kanji1. The kanji used in 休む (yasumu, to rest), for example, is a combination of 人 (hito, person [often written as ⺅ when used as a radical]) and 木 (ki, tree)1. A lot of the time, the two simpler kanji are chosen because of their connection to the resulting character. For 休, a person leaning against a tree would be resting – which is why 人 and 木 were chosen to form this character!

4. Phonetic-ideographic Characters

These kanji are usually found when a character’s original on-yomi sounded like a native Japanese word, but the kanji associated with the sound didn’t represent the word’s meaning. So, to remedy this, those in the past added an additional kanji to clarify the meaning. In other words, these kanji are formed by combining one kanji that has the word’s pronunciation and another kanji that represents the word’s meaning. One example of this is the character for sei (clean). Water is generally associated with cleaning, so the kanji for water 水 (mizu, often written as ⺡) is added to the kanji 青 (sei, blue) to get 清 sei (clean).

As you can see, kanji are definitely more complex than hiragana or katakana, but don’t worry – there are plenty of simple kanji too! Plus, knowing the radicals and kanji types will help to make learning and remembering kanji easier. Knowing the stroke order, or the steps in which each character is written, can help make memorization easier too; check out this site to look up any kanji and see its stroke order (and other helpful information)!

Uses

Kanji is used for nouns, verb stems, and adjectives. So, kanji are used for most major words that you will encounter in everyday Japanese! While hiragana and katakana are crucial, you also can’t rely on just those when reading and writing; you have to learn kanji as well!

Example

Let’s take one last look at Bob, this time reading the sentence as it would be written in everyday Japanese:

私のペットの名前はボブです。

Watashi no petto no namae wa bobu desu.

Well, using kanji certainly makes the Japanese sentence shorter! In this case, the pronoun watashi (I) and the noun namae (name) use kanji. If there was a different verb in this sentence (like “look” or “ate”), then there would most likely be kanji there as well. Finally, using these new symbols makes the sentence even easier to read, as they are visually quite different than hiragana or katakana!

While all of this might seem overwhelming at first, it’s nothing you can’t handle with a little practice! Simply writing the kanji out is a great way to see how the radicals work together and to memorize their combinations; but, if you’re looking for something a little bit more high-tech, there are also some kanji apps we recommend you can use to practice as well!

Conclusion

Well, we certainly covered a lot of ground today! Let’s review everything to make sure you remember what we learned.

Japanese has three types of writing systems: hiragana, katakana, and kanji. Hiragana is curvy, represents small syllables, and is used for grammatical information, particles, and native Japanese words! Katakana is straight, also represents small syllables, and is used for loanwords from other languages. Kanji are complex characters made up of radicals, represent a concept, a sound, or a mixture of the two, and are used for nouns, verb stems, and adjectives.

And those are the main points! Not so bad, right? You are now ready to start reading and writing Japanese like a pro! If you feel like you need more help, though, feel free to reach out to us or join one of our many Japanese language classes here!

FAQ

What is the Japanese writing system?

The Japanese writing system uses Hiragana, Katakana, and Kanji scripts.

What does Hiragana represents?

Hiragana represents native Japanese words, grammatical particles, and verb endings.

What does Katakana represents?

Katakana represents foreign words, loanwords, onomatopoeic words, and emphasis.

How many characters are there in hiragana and katakana?

There are 46 characters in each of the Hiragana and Katakana scripts.

What is the closet thing to English chracters?

There is no such thing as the Japanese alphabet, but the closest things would be called hiragana and katakana.

How many kanji I should learn?

To be considered fluent in Japanese, you must learn from 1500 to 2500 kanji characters.