The question that perplexes all Japanese learners at the beginning: Why is ha (は) read as wa in Japanese, sounding exactly the same as わ? We all thought Japanese phonetics was pretty straightforward, but just when you think you’ve nailed the hiragana and katakana writing systems, you come across this conundrum.

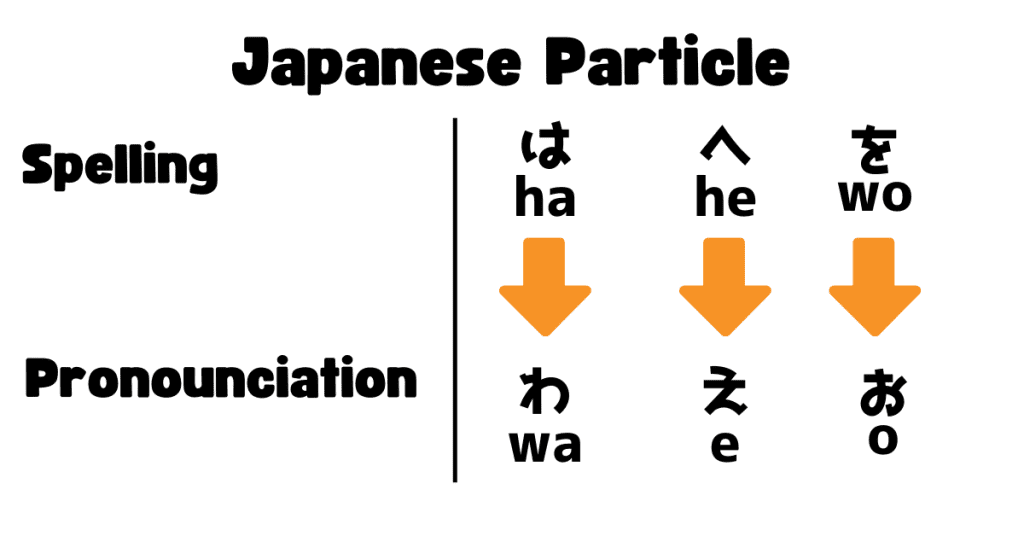

Of course, once you’re used to reading, writing, and speaking Japanese, this problem is less of real concern and more of an annoying tick. It doesn’t matter. It is what it is. No one really knows the answer, right? The same thing goes for へ (he), which is sometimes pronounced as ‘e’, and を (wo), which is always pronounced as ‘o’.

But exploring the cultural significance and history of Japan can help you better understand the language. And if you’re left exasperated by the cookie-cutter answer, we’re here to give you a deep dive into the complex world of the Japanese language and linguistic evolution.

The Short Answer to Why We Pronounce Ha (は) as Wa (わ)

In grammar, は marks the topic of a sentence and is pronounced “wa” instead of “ha.” This is a special rule from classical Japanese that stuck — even though it’s written は, it’s spoken as “wa” when used as a particle.

Let’s take a look at three examples first, containing both the Japanese letters は and わ.

おはようございます。

Ohayou gozaimasu.

Good morning.

今日はいい天気ですね。

Kyou wa ii tenki desu ne.

The weather is good today.

私の名前はコトです。

Watashi no namae wa Coto desu.

My name is Coto.

You may have pronounced the は and わ differently, or even interchangeably. You reflectively say kyou wa instead of kyou ha. Ohayou instead of owayou. And that’s great. That means you already know the proper Japanese phonetics.

So did the sounds of these particles change since the spelling was set down? Or were the spellings intentionally chosen for some reason? Are there any other irregular kana spellings omitted?

The short answer is simple, really: if the は is used as a Japanese particle, it is pronounced as ‘wa’. The particle は is the topic particle that identifies the topic of your sentence.

If it’s used to build a Japanese word, as adjectives, adverbs, nouns, or even names, it goes back to its original pronunciation: ha.

This is why the word おはようございます, which contains は, retains the typical ‘ha’ pronunciation. In the second and third sentences, は is the particle to help make the subject stand out: My name is Coto. Today is good weather.

The same thing for the character へ. Used in words, it is pronounced: “he”. When it’s a particle, it is pronounced: “e.”

The Evolution of Japanese Language Phonetics: Wa and Ha

The particle は is still pronounced “wa” because it’s a historical spelling rule that dates back to classical Japanese. Over time, the pronunciation of Japanese sounds evolved, but a few traditional particles kept their old spellings. While most words were updated to match modern pronunciation, particles like は (wa), へ (e), and を (o) kept their original written forms for grammatical consistency — a linguistic “fossil” from Japan’s past.

If you’re still unsatisfied with that answer, we get it. Why is the は particle specifically an exception? How did the sound and rule evolve into what they are in the present day? That short explanation might have just opened more doors to even more questions.

The truth is, discrepancies between spelling and pronunciation are common, no matter the language. You’ll probably notice it in English more than in Japanese. Take the word tongue or island, for example. The Japanese language is no different, although the fact that the current Japanese spelling is almost completely phonemic makes anomalies like this stand out more.

Only a handful of traditional spelling quirks remained, and using は for the particle that is pronounced wa is one of them.

In fact, this is what you need to know this: just like society in general, language is ever-changing, and the sounds made by characters will shift over time.

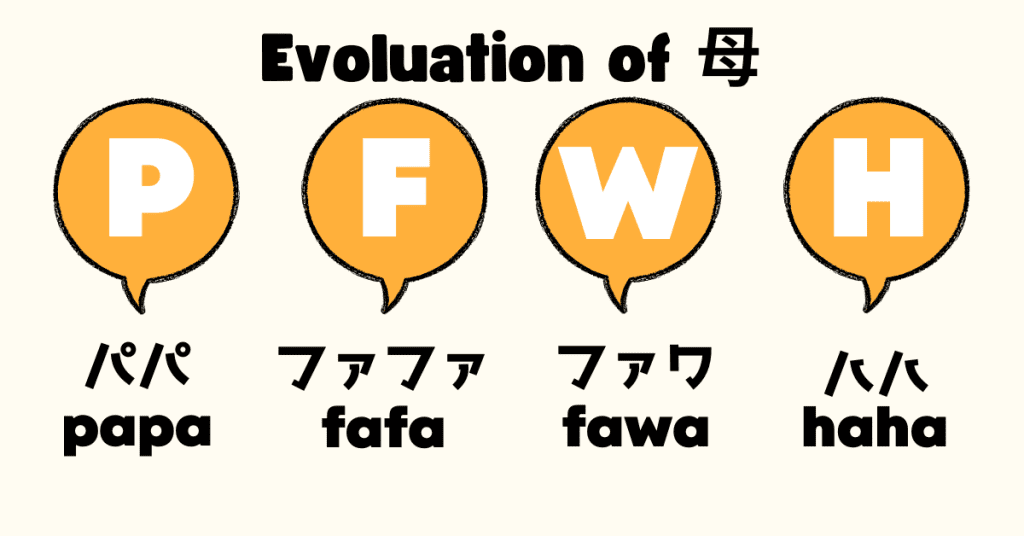

In the early history of Japanese (before 800 BC), the modern は row of consonants, comprised of は, ひ, ふ, へ, ほ were pronounced with ‘P’ as pa, pi, pu, pe, po.

Enter the Nara Period (710 to 794). The ‘P’ sound underwent another change, shifting to a softer F sound: fa, fi, fu, fe, fo. This pronunciation stayed until the 16th century, judging from the transcripts made by the Portuguese of Japanese words that use the letter F where we would use H today.

For example, take the Japanese word for “mom”: 母. Today, it’s spelled as はは and pronounced as haha. In the old Japanese, the word is pronounced as fafa.

After the Nara Period came the Heian Period (794 to 1185), where we see another shift: the F sound changed to W, but with a catch: the sound altered only when there was another vowel and when it was not at the beginning of the word.

The pronounciation changed from:

は ひ ふ へ ほ

ha hi hu he ho

to:

は ひ ふ へ ほ

ha hi hu he ho

This led to a verb such as 買う (買フor kafu in old Japanese) to be read as Kau (stemmed from kawu). The negative form of this verb underwent the same changes: instead of kapanai, it became kawanai.

母 turns into fawa. The word for river, once pronounced as kafa, became the modern-day kawa.

This marked the beginning of the transition where は is pronounced as わ. The particle は, which regularly appears after a vowel, was soon normalized as wa.

Eventually, in the Edo Period (1603 to 1867), people from various regions of Japan start to gather in Edo (the old Tokyo), This resulted in various dialects mixing and diluting. Eventually, the ‘F’ sound changed again to the H sound.

Now, the 母 finally settled to its modern pronunciation that we know today: haha, spelled as はは. However, at that time, despite the new pronunciation, the words still used the old kana that represented the old pronunciation.

This was the main linguistic problem. Up to World War 2, although the changes from the initial P sound to W sound were then widely accepted, the people still used historical usage.

This meant 買う was still written 買フ (kafu) and 買わない was written as 買ハナイ (kahanai). Of course, the lack of standardized writing meant there was still a lot of confusing spelling.

The Japanese Language Reform Changes Writing and Spelling

After World War 2, the Japanese government did a massive language reform to its writing and spelling rules to make things more even across the country. Remember the part where we said a lot of people from regional Japan were gathering in one capital? That was a huge wake-up call.

So they decided to clean up the spelling and pronunciation of syllables. The official spelling of words needed to match the new pronunciation rules so that people wouldn’t think the word was supposed to be pronounced a different way. All ‘ha/は’ letters read as “wa” sounds were replaced with wa/わ. 川(かは) now was written as 川 (かわ). The kana へ, which was once pronounced e (now it’s he).

So Why Does The Particle Wa (は) Stick With The Old Spelling?

The problem with change is that it’s usually easier said than done. Imagine this: close to a hundred million people in a country are following one unsaid linguistic rule. You can change the texts, rules and writing across all books and paper, which in itself is already a mammoth task, but you can’t change a society’s collective habit instantly.

Now Japan has all these written texts where the wa ワ is written with the old Japanese rule: wa は kana. At the same time, the other は kana was now pronounced ha (ハ).

And how do you make the entire nation write the wa は particle as wa わ?

Simply put, it was too much trouble for Japan to try and make this change work — revamping the entire text, scripts and liteature for two particles was not worth it. The particles were excepted because many felt that changing these exceedingly common spellings would confuse people.

There you have it: up until today, we are saying the は particle according to the modern-day Japanese pronunciation, but the reason why it’s still spelled as ‘ha’ は and not わ is because we are still sticking to its traditional spelling.

Modern pronunciation. Traditional spelling. Remember that.

Let’s Get Straight to The Point: Why Ha (は) Is Read as ‘Wa’

To sum up, は is pronounced as わ because the transcript reflects pronunciation that did not change during the language reform. The sound わ used to be written は in old kana usage in some cases. Old kana usage was much more irregular than it is nowadays.

At that time, it was decided that for the particles alone, the same letters that had been used should continue to be used even though they are different from the actual pronunciation.

Other Japanese Particles: Why を Is Read as “O” and へ as “E”

It’s the same thing with the readings for the particles へ and を too. The modern sound え used to be written as へ in some cases and お as を. Of course, pronunciation varies and sometimes you can hear a clear difference between お and を for instance. Still, in all words, besides the particles, the old pronunciation differences have disappeared as time has passed.

There is an exception to the “wa” rule besides the Japanese particle, though. When は is used as the last letter of the greeting phrase, it follows the sound of a ‘wa’ particle.

こんにちは

Actual spelling: Konnichiha.

Pronounciation: Konnichiwa

こんばんは

Actual spelling: Konbanha

Pronounciation: Konbanwa.

| Original Kana | Pronunciation (Before Reform) | Modern Pronunciation | Modern Spelling | Example Word | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| は (ha) | “wa” (in certain words) | wa | わ | かわ (川) | river |

| へ (he) | “e” (as a particle) | e (when a particle) | へ (unchanged) | 学校へ行く | go to school |

| を (wo) | “o” | o | を (unchanged) | パンを食べる | eat bread |

To Sum It Up

There you have it: the core reason behind this ‘problem’ is simply because Japan never bothered to fully fix the two particles they spelled “wrong”. Instead, they went the easy route and deemed it as the official, right way to do it. Problem solved.

The good news is that you’ll only have to deal with these in hiragana. Katakana is almost exclusively for foreign words, so you’re not really going to see particles written in katakana.

Want to learn more about the Japanese language? Head to Coto Academy

Like what you read? We have tons of fun, easy-to-read learning content that makes your Japanese studies less like a study. But if you want more support from a native teacher, connect with friends who share the same love for the Japanese language and study in a classroom, Coto Academy is your choice.

We offer a relaxed, cozy learning environment for students of all levels. Join our intensive Japanese course or part-time intensive courses!

Want to study Japanese with us?

FAQ

Why is the hiragana “は” pronounced “wa” in some sentences?

In Japanese, when “は” is used as a particle to mark the topic of a sentence, it is pronounced “wa.” This is a special grammatical rule, not a mistake or typo.

Why does Japanese use “は” instead of just writing “わ” for the particle?

It’s a result of historical spelling. Hundreds of years ago, Japanese pronunciation shifted over time, but the spelling for certain grammatical particles remained the same. The particle は was kept to preserve consistency in written grammar.

Why is "ha" used instead of "wa" in "Konnichiwa"?

In “こんにちは” (konnichiwa), the final character “は” is actually the topic particle, even though it looks like part of the word. The phrase is a shortened form of a longer greeting that originally ended in the particle は — so it’s pronounced “wa.”

Why do Japanese add “wa” at the end of sentences?

In casual or feminine speech, “wa” (わ, different from the particle は) can be added at the end of a sentence for emphasis or tone. It adds softness, emotion, or emphasis, often in a light or expressive way. Example: かわいいわ (kawaii wa) = “So cute!”