While China and Japan may be relatively close geographically and both shape today’s cultural, economic, business, and pop culture landscapes, the Chinese and Japanese languages have clear distinctions.

The Chinese language is estimated to be spoken by more than one-fifth of the world’s population. Japanese, on the other hand, is primarily spoken in Japan. And due to the massive influence and reach of both China and Japan, many language learners often struggle with the dilemma of choosing whether to learn Chinese or Japanese, and the fundamentals of what makes each language so special and unique from the other.

In this article, we will help distinguish between the Chinese and the Japanese languages so that you can adopt a greater appreciation and understanding of each one, and determine which language is more aligned with your language learning wants and needs!

History of the Chinese and Japanese Languages

Chinese Language

The Chinese and Japanese languages have ancient roots, tracing back thousands of years for both written and oral communication. The modern Chinese language originated from the Proto-Sino-Tibetan language family, which emerged in the Yellow River region of northern China approximately 6,000 years ago. The historical timeline of the Chinese language can be divided into 4 distinctive eras:

- Ancient Chinese: 18th century BC – 3rd century AD

- Middle Chinese: 4th century AD – 12th century AD

- Early Modern Chinese:13th – 20th century

- Modern Chinese: 20th century to present day

Each of these evolutionary eras marks a distinct shift in both the spoken and written Chinese language.

For instance, Ancient Chinese featured many monosyllabic consonants (a word with only one syllable, ex. “hi” or “see”) and lack of inflections (changing a word’s form to align with a certain tense, ex. “chased” or “jumped”), marking the early emergence of a language without the later fine-tuning and specifics quite yet.

Middle Chinese marked the early development of tonal variation, including level (píng) — a stable pitch, rising (shǎng) — a pitch that rises during the syllable, and departing (qù) — a falling pitch. During this period, the distinction between aspirated and unaspirated sounds also emerged. Aspirated sounds required a stronger burst of air upon pronunciation, whereas unaspirated sounds involved much less airflow.

Early Modern Chinese set the groundwork for the Chinese that we recognize today, including more disyllabic words (a word with more than one syllable, like “sunshine” or “rainbow”), as well as the gradual shift towards Mandarin.

Modern Chinese marks a significant change as the Mandarin dialect, which emerged in Beijing, becomes the official language across China and is widely spoken by the vast majority of the Chinese population.

Japanese Language

The Japanese language is a member of the Japonic family, which comprises all of the languages spoken on the Japanese islands. The origins of the Japanese language date back approximately 2,000 years, coinciding with the Yayoi peoples’ arrival on the Japanese islands. The Japanese language can be sectioned off into three evolutionary categories:

- Old Japanese: 710-794

- Early Middle Japanese: 800-1200

- Late Middle Japanese: 1200-1600

- Modern Japanese: 1600 to present day

The Japanese language developed across each of these distinctive eras. Old Japanese utilized Man’yogana, which was an ancient Japanese writing system that focused on sounds derived from Chinese characters to convey meaning instead of a literal translation, as well as the introduction of a basic syllable before it later advanced.

Early Middle Japanese saw the beginning stages of hiragana (native Japanese words) and katakana (loan words from foreign languages) in the written Japanese language, as well as an increased volume of words borrowed from Chinese characters to implement their meaning into the Japanese language, known as kanji.

Late Middle Japanese saw the erasure of many nominal inflections (modifying a noun to adjust to a new element such as number or possession, like “horses” or “the horse’s hay”), which were previously used, as well as the introduction of loan words (katakana) from English.

An important aspect of Modern Japanese as we know it today is the introduction of keigo, which is an honorific language that modifies words and titles depending on who the speaker is talking to and the degree to which they are showing respect or familiarity. The modern era also saw increased romaji, or romanized spelling of Japanese words (like “arigato gozaimasu” or “sumimasen”). If you are interested in tips and tricks to learn for newcomers to the Japanese language, take a look at our article detailing how to learn Japanese from scratch.

Chinese vs Japanese Writing Systems

The Chinese and Japanese writing systems are quite different from one another in many ways.

Chinese Writing System

First and foremost, Chinese utilizes two writing systems called hanzi, which encompasses all Chinese characters, both traditional and simplified, and pinyin, which uses the Latin alphabet to convey Chinese sounds. There is also zhuyin, which is predominantly used in Taiwan to transcribe sounds from Mandarin.

Japanese Writing System

Japanese, on the other hand, has three writing systems. It utilizes hiragana, which includes all native Japanese words; katakana, which is used for foreign loan words; and kanji, which is composed of logographic Chinese symbols. For an in-depth look into the Japanese writing systems, check out our article diving into hiragana, katakana, and kanji.

While Japanese may borrow certain logographic symbols from Chinese, the pronunciation can be entirely different. For example, the logograph 水 (shuǐ) means water in Chinese, and the Japanese Kanji for water 水 (mizu) are identical in terms of character and meaning, but are pronounced differently.

Chinese also has simplified and traditional characters, unlike Japanese. Simplified characters are easier to write and involve fewer intricate details, while traditional characters are more akin to historical accuracy but involve far more complex designs. Simplified characters are often utilized in mainland China and Taiwan, while traditional characters are more common in the special administrative regions of Hong Kong and Macau. Japanese also has its own writing system composed of simplified Kanji, called shinjitai.

Want to start learning Japanese? We recommend joining conversation-focused beginner lessons at Coto Academy, available on a part-time or full-time basis. You’ll build a solid foundation in hiragana, katakana, and essential grammar, while gaining confidence to speak Japanese from day one.

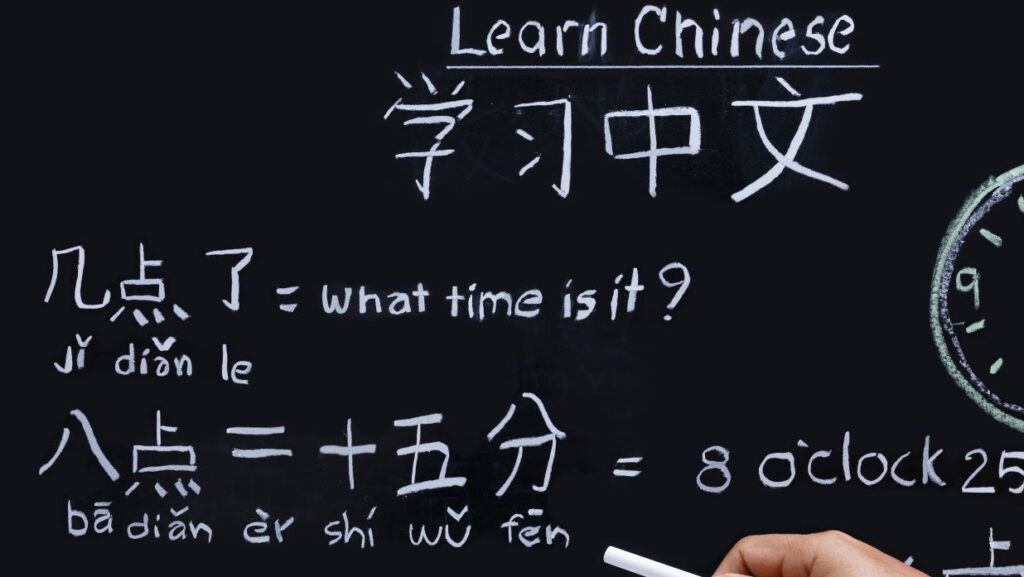

Pronunciation and Phonetics

Chinese and Japanese pronunciation differ quite a bit from one another. Before we discuss the differences between the two, it is helpful to understand the key differences between pitch and tone as they relate to language. Pitch is what conveys the emotion or emphasis on a word, while tone utilizes pitch to create an entirely different meaning of a word.

Chinese Language

Chinese is a tonal language, with four distinct tones that can change the meaning of a word entirely. In the Modern Chinese language, the four tones are:

- 1st tone: level pitch (ex. wēn) where you maintain a high and steady pitch

- 2nd tone: rising pitch (ex. wén) where you begin with a middle pitch and increase to a higher pitch

- 3rd tone: falling-rising (ex. wěn), whee you begin with a middle pitch and then lower it, then proceed to raise your pitch again

- 4th tone: falling (ex. wèn), where you start off high-pitched and then sharply drop your tone

Depending on the tone used, the meaning of the word above changes significantly, so mastering tones is a key element of learning the Chinese language!

There is also a “neutral tone” in Chinese, although it is not considered its own tone; rather, it is considered an unaccented and unstressed syllable and lends its pitch to whichever tone appeared before it, as the neutral tone cannot exist alone.

Japanese Language

Japanese is far less reliant on tonal variations to convey meaning. However, the importance of pitch is still prevalent in the Japanese language, with high and low pitches distinguishing words that are otherwise pronounced the same.

Before we discuss the different pitches and how to make them, we must first understand what a mora is.

Mora is the unit of sound that the Japanese language follows, similar to a syllable in English. However, moras are unique since they are given equal length, whereas syllables can be given unequal length in terms of time. An example of this is バス (basu) versus bus, with ba-su being two moras and the English spelling of bus only having one syllable. With this information taken into account, the four pitch patterns in Japanese are as follows:

- Heiban (平板). Unaccented and flat (most Japanese words fall under this category)

- Atamadaka (頭高). The first mora begins high, and then the second mora drops to a low pitch

- Nakadaka (中高). The first mora is low-pitched before transitioning to a higher pitch in the middle, and then falling back to a low mora

- Odaka (尾高). The first unit is flat and then rises to a high pitch for the duration of the word

For example, “ame” can mean either rain (雨) or candy (飴) depending on the pitch, with rain being a higher-pitched and candy being lower-pitched.

If you are interested in learning more about the intricacies of the Japanese language and what makes it challenging to learn, feel free to read our other article detailing why Japanese is a challenging language to learn. Context clues can help Japanese learners differentiate between meanings and are more beginner-friendly since a Japanese speaker can likely still understand what is trying to be said, whereas Chinese is more difficult as improper tonal variation makes it far more difficult to discern the intended meaning.

Grammar Sentence and Structure

Chinese sentence structure uses subject-verb-object (SVO) order, while Japanese structure consists of subject-object-verb (SOV) order.

An example showcasing this differentiation is the sentence “I listen to music” in Chinese and Japanese.

In Japanese, it is “私は音楽を聴きます” (Watashi wa ongaku o kikimasu), or “I music listen to” if translated literally into English.

The same sentence in Chinese would be “我听音乐” (Wǒ tīng yīnyuè), or “I listen to music”, which sounds more familiar to speakers of SVO languages, including English.

Japanese grammar also differs quite a bit from Chinese grammar when it comes to affixes, which are additions to the beginning or end of a root word to alter its meaning and purpose. This is represented by the usage of honorifics such as -chan (ちゃん), -san (さん), -sama (様), and -kun (君), which are added onto the end of a person’s name to convey varying levels of relation and formality. While Chinese also utilizes honorifics, it is far less integral grammar-wise to the overall structure and tone of a sentence than is the case in Japanese.

Verbs in Chinese vs Japanese Language

The ways in which verbs are used and modified in Chinese vs. Japanese writing marks another area in which the two languages contrast with each other.

In Chinese, verbs do not inflect and remain the same regardless of the tense or number; instead, the usage of particles such as 了(le) for completed actions and 在 (zài) for actions which are still being undergone indicates tense. An example of this is “I swam” or “ 我游泳了” (Wǒ yóu yǒng le), as well as “I am swimming” or “我在游泳” (Wǒ zài yóu yǒng). On the other hand, Japanese verbs can be altered depending on aspects such as tense, negation, and politeness level. For example, some forms of “to eat” include:

| Japanese | Meaning | Formality |

| 食べます (tabemasu) | To eat | Formal |

| 食べません (tabemasen) | Don’t eat | Formal |

| 食べました (tabemashita) | Ate | Formal |

| 食べる (taberu) | To eat | Informal |

| 食べない (tabenai) | Don’t eat | Informal |

| 食べた (tabeta) | Ate | Informal |

As you can see, there are many different ways in which verbs can be conjugated in Japanese! Saying “to eat” in Chinese, on the other hand, would simply be 吃 (chī), regardless of any and all factors which may influence Japanese conjugation.

Vocabulary and Share Words: Japanese vs. Chinese Characters

Many Japanese characters are borrowed from Chinese logograms (kanji), intrinsically linking certain parts of Japanese vocabulary with those of Chinese.

Surprisingly, Japanese features far more foreign loan words (katakana) than Chinese, with Chinese placing more emphasis on translating the meaning of the word rather than the sounds produced. As a result, certain Kanji can be recognized by Chinese speakers, and borrowed words such as テレビ (terebi), カメラ (kamera), and ホテル (hoteru) can be understood by English speakers, giving Japanese vocabulary much more foreign influence than Chinese vocabulary.

In the case of Kanji, however, pronunciation may differ from its Chinese origins. A few of these “false friends” include:

| Logograph | Chinese | Japanese |

| 老婆 | Lǎo pó (wife) | Rouba (old woman) |

| 汽車 | Qì chē (car) | Densha (train) |

| 走 | Zǒu (to walk) | Hashiru (to run) |

| 床 | Chuáng (bed) | Yuka (floor) |

Similarities Between Chinese and Japanese Languages

While both Chinese and Japanese may have many differences from one another, there are also a few noteworthy similarities that the two languages share. As discussed previously, a sizable portion of Japanese words are derived from Chinese logograms, oftentimes with shared meanings even if the pronunciation differs. Examples of this include:

| English | Kanji | Japanese (JP) | Chinese (CN) |

| Person | 人 | hito | rén |

| Mountain | 山 | yama | shān |

| Fire | 火 | hi | huǒ |

| Fish | 魚 | sakana | yú |

Another similarity between Japanese and Chinese languages is the name order placement, with the family name coming before the first name in both introductions and in writing.

Additionally, the use of measure words is a commonality shared between Chinese and Japanese, which is a concept that classifies the specific objects or things that are being counted. For example, when counting people, instead of using the generic numberings of ichi (1), ni (2), san (3) in Japanese or yī (1), èr (2), sān (3) in Chinese, there is a specific counting system that the category of “people” falls under. Hitori, futari, sannin, and so on, and yī rén, liǎng ge rén, sān ge rén, and so on are the counting systems that would be used to count people in Japanese and Chinese, respectively.

So, Which is Easier? Chinese or Japanese Language?

Now that we have done a deep dive into Chinese and Japanese languages, it boils down to the question: which one is easier?

Both the Chinese and Japanese languages have their fair share of language-specific and common difficulties, so learning each will be a rewarding challenge for those who are willing to tackle it head-on. However, taking into account all the factors we have discussed in this article and our comparisons of the two languages, the question of “which language is more difficult?” ultimately boils down to two categories: speaking and writing.

In relation to speaking, Chinese is more difficult than Japanese due to the complex tones, which require hard work and discipline to be able to master and discern during spoken conversation.

Japanese, on the other hand, is not reliant on tone and is easier to speak and understand, with more leeway in terms of context clues and less need for a trained ear. On the other hand, in terms of writing, Japanese is more challenging than Chinese due to the three writing systems (hiragana, katakana, kanji) and more complex grammar and sentence structure. Being already familiar with Chinese will give you a helpful upper hand! Check out our article detailing the unique relationship between understanding Chinese and learning Japanese.

Which Language Should You Learn?

Both Chinese and Japanese are challenging yet rewarding languages to learn, and both will offer you great satisfaction. So, which one should you study? If you are planning on living, studying, or working in either China or Japan, then you should learn the native language of the respective country.

Chinese language is a great choice if you plan on going into business, economics, or international relations due to its global dominance and power. Japanese, on the other hand, is an amazing choice due to its worldwide influence in the entertainment, media, technology, and pop culture spheres. Or if you simply want to learn a language for fun, then both are great options!

Conclusion

Both Chinese and Japanese are becoming increasingly popular languages to learn, and Japan is quickly emerging as a top destination for people looking to build their careers.

The good news? If you’re a native Chinese speaker, learning Japanese can be easier than you think! That’s where Coto Academy’s Intensive Japanese Lessons come in.

Our programs are designed to support learners at every level, from complete beginners to advanced speakers. With experienced teachers, immersive lessons, and a clear, step-by-step approach, you’ll strengthen your grammar, expand your vocabulary, and gain confidence using Japanese in real-life situations. Chinese learners can also take full advantage of their kanji knowledge while focusing on areas that need extra attention.

And for English speakers deciding between learning Japanese or Chinese, why not start your journey with Coto Academy? If you choose to learn Japanese, join our well-balanced lessons that focus on every aspect of the language: grammar, kanji, vocabulary, reading, and listening — all while getting plenty of conversation practice.

Why join Coto Academy?

- Small classrooms with only up to 8 students for personalized support

- Professional native Japanese teachers, all trained to help you succeed

- Over 60 different Japanese classes across 18 levels, tailored to your needs

- School locations in Shibuya, Minato, Iidabashi, and Yokohama, plus a fully online Japanese language school, so that you can learn anywhere, anytime!

FAQ

How different are the Chinese and Japanese languages?

Chinese and Japanese are very different languages, even though Japanese borrows a large amount of Chinese logograms. The Kanji pronunciation of these logograms often differs greatly from the pronunciation in Chinese. Chinese also follows the SVO order, while Japanese follows the SOV order in terms of sentence structure. Additionally, Chinese utilizes complex yet subtle tonal changes to convey the meaning of a word, while Japanese utilizes pitch to a lesser extent.

Can a Chinese person understand a Japanese person?

No, a native Chinese speaker and a native Japanese speaker would have a lot of difficulty understanding each other. Chinese is heavily reliant on tones to convey meaning, which makes it quite a lot different from Japanese, which is more based on pitch. Similarly, Japanese Kanji can be pronounced differently from the Chinese pronunciation, even if the logograph itself conveys the same meaning.

What is the 80/20 rule in Japanese?

The 80/20 rule is the idea that if you know approximately 20% of the Japanese language, you will be able to get by in 80% of scenarios in Japan. If you understand even a quarter of the language, navigating Japanese life will become much easier and smoother.

What is the difference between Chinese and Japanese characters?

The Chinese language utilizes one system (hanzi), while the Japanese language uses three systems (hiragana, katakana, and kanji) for its writing systems.