Kanji can be beautiful, but some of them can also be downright intimidating. While most learners start with simple characters like 日 (day) or 木 (tree), Japanese writing also hides a few monsters: characters so complex and rare that even native speakers may pause before reading or writing them.

So what are the most difficult Japanese kanji characters? Japanese kanji are hard to learn on itself, but let’s take a look at the world’s most difficult Japanese kanji with the most number of strokes!

What is kanji?

Originating from China, kanji takes a significant part in the Japanese language. It is widely used in the daily life of the Japanese people. Usually, a Japanese person grown up speaking Japanese knows about 3500 to 4000 Kanji.

Although kanji can be replaced with kiragana or katakana, it only makes a sentence harder to read and comprehend. For example, how do you differentiate between 橋 (はし), 箸(はし), or 端(はし) if expressing them in hiragana?

As a result, learning kanji is very important. Just started learning Japanese? Head to our main article about the Japanese writing system for a more comprehensive guide on hiragana, katakana, and kanji!

The Most Difficult Japanese Kanji on Record: たいと(Taito)

たいと(taito) is the most difficult Japanese Kanji on record, with a total of 84 strokes. It is formed by combining 3 雲 (くもkumo) with 3 龍 (りゅうRyuu). 雲 means cloud and 龍 means dragon in English. たいと is said to be a type of Japanese surname. Although this kanji is recorded in the Rare Surname Dictionary, its true existence is still unverifiable.

Feeling mindblown? There are more extremely difficult Japanese kanji! Take a look at each of them, and you will understand how complicated kanji can be.

Hardest Kanji Characters with Most Strokes

Of course, the kanji with the most strokes isn’t always the hardest, but it does tend to get more complicated as the stroke count increases. More strokes mean more details to memorize, and when writing them by hand, you have to be even more careful to keep every line precise and balanced.

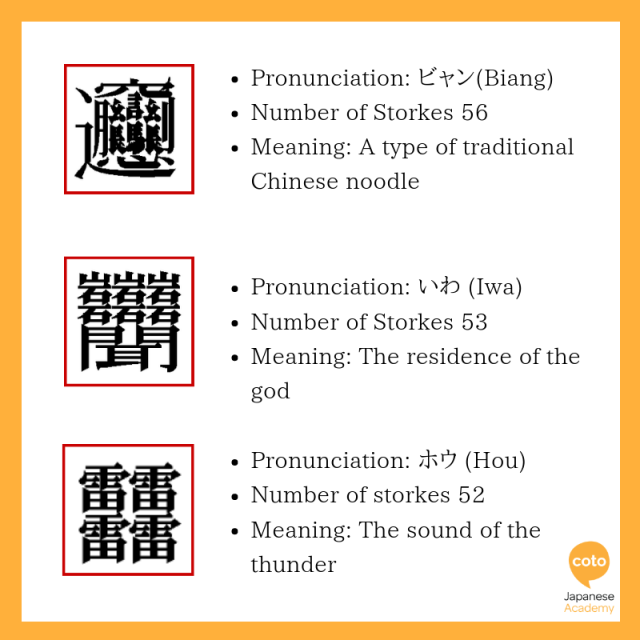

1. びゃん (Biang)

Arguably the most famous “difficult kanji” in the world, the character for biang boasts over 50 strokes and doesn’t exist in the standard Japanese or Chinese character sets. It appears in the name of a regional noodle dish from Shaanxi Province in China called biángbiáng noodles. Although it’s mostly used as a linguistic curiosity, it has become a kind of cult symbol for fans of complex characters. Thankfully, the more common kanji for noodles, 麵 (men), is far simpler—though still on the elaborate side.

2. いわ (Iwa)

The common kanji for iwa (rock) is 岩, which is simple and widely used. But there’s another rare version of iwa that means “residence of the gods” and clocks in with a staggering 53 strokes. This kanji is visually arresting: it stacks three 岩 (rock) characters above another complex base, forming an imposing symbol.

While not in daily use, it serves as a poetic way to represent sacred ground or spiritual locations.

3. ほう (Hou)

The kanji 雷 (kaminari or rai) means “thunder,” but what happens when you multiply it by four? You get a visually dramatic compound. This version isn’t used in official writing systems and is more of a creative or poetic invention. It emphasizes loudness, repetition, and the raw force of nature

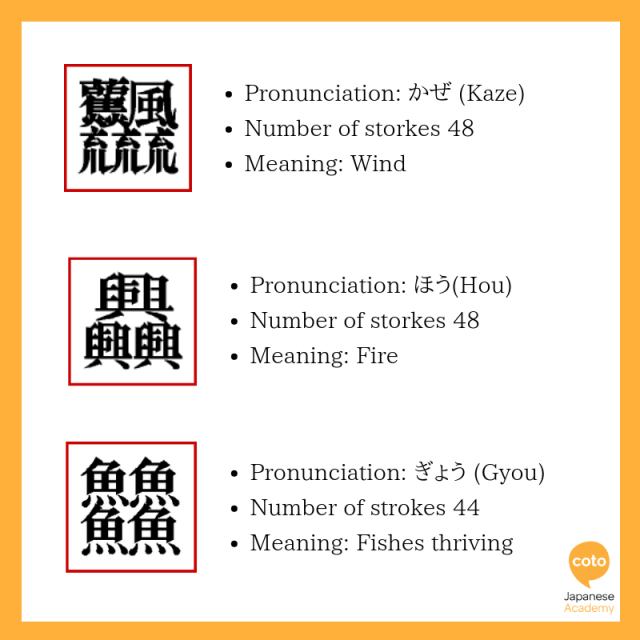

4. かぜ (Kaze)

The everyday kanji for kaze (wind) is 風, which is relatively simple. However, the version shown here is an ornate, stacked compound incorporating repeated radicals like 飛 (fly) and 流 (flow). We think this is to evoke the swirling and dynamic movement of strong winds.

5. ほう (Hou)

At first glance, the complex kanji for hou may seem like it represents fire, but its root character, 興, actually means “to rise” or “to flourish.” In this case, 興 is repeated three times, perhaps to suggest intensity or prosperity. Though it’s sometimes associated with flames or passion, it doesn’t directly mean “fire.” Instead, this triple-stacked variation seems to be a poetic exaggeration.

6. ぎょう (Gyou)

This character features a triple stacking of 魚 (fish), much like how the forest kanji 森 is made from three trees. While 魚 alone simply means “fish,” stacking it three times symbolizes abundance and prosperity, like a thriving underwater world. Though not in official use, this visual shorthand for “many fish” is sometimes used symbolically.

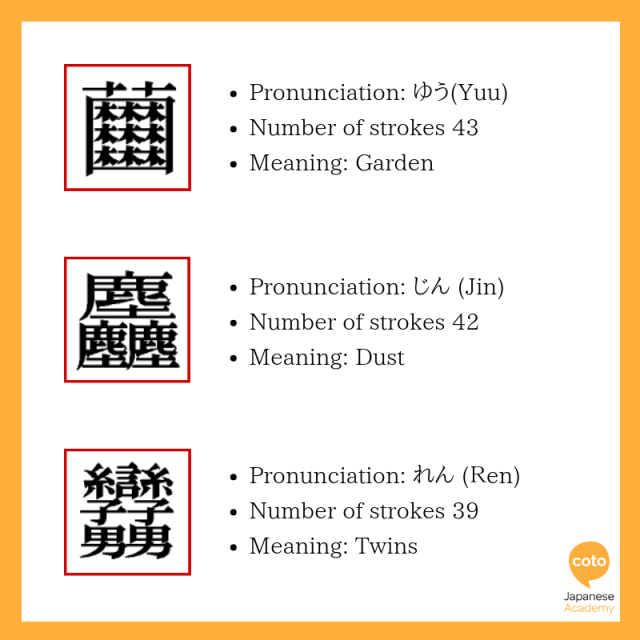

7. ゆう (Yuu)

The character for yuu, meaning “garden,” may be a decorative or stylized alternative to 園 (en), the standard kanji used today. It appears to incorporate common garden-related radicals such as 艸 (grass), 門 (gate), and 囗 (enclosure).

8. じん (Jin)

Although sometimes translated as “dust,” the rare character 麤 (so or sou) more accurately means “rough” or “coarse.” It’s formed by stacking the kanji for “deer” (鹿) three times. Used in classical Chinese texts, this character conveys the idea of something impure or unrefined. Its towering complexity makes it a challenge to write, but its meaning is more textured than it first appears.

9. れん (Ren)

This fictional kanji combines 糸 (thread), 子 (child), and two 勇 (bravery) characters to symbolically represent “twins.” While it doesn’t appear in any official dictionaries, the intention is clear: children, connected like a thread, and reinforced with a sense of strength and duality.

Other Difficult Everyday Kanji

So far, we’ve looked at archaic kanji that rarely appear in daily life or writing. But what about the challenging kanji you actually encounter on the go? Japanese writing still features plenty of difficult characters in everyday situations. Here’s a breakdown of real-life kanji that stand out for their high stroke count, obscure readings, or unusual components:

1. 機械 (Kikai)

Meaning: Machine

Stroke counts: 27

The kanji for machine is high in strokes and contains radicals like 木 (tree) and 戈 (halberd). These are common in technical or formal writing, especially in manuals or product descriptions, but they trip up learners due to their complexity and similar appearance.

2. 綺麗 (Kirei)

Meaning: Beautiful

Stroke count: 28

These kanji are often learned later in study, but they appear frequently in daily language. Their complex structure and unusual radicals (like 糸 for thread and 鹿 for deer) make them harder to write from memory, even though the word itself is common.

In fact, the kanji for きれい (kirei) is somewhat annoyingly difficult for Japanese people, so they also tend to spell it out in either katakana (キレイ) or furigana.

3. 鬱 (Utsu)

Meaning: Depression, gloom, or melancholy.

Stroke count: 28

One of the most complex kanji in standard use, 鬱 has 29 strokes. It appears in psychological and medical terms such as 鬱病 (うつびょう), meaning depression. Though difficult to write and recognize, it’s crucial in Japan’s mental health contexts.

You’ll also frequently see it paired with the character 憂 (ゆう/うれ/うれ/う) in the compound 憂鬱 (ゆううつ), which means gloomy, melancholy, or sad.

The kaji is so complicated that often, it is replaced by kana or the simpler form ウツ in informal writing.

4. 薔薇 (Bara)

Meaning: Rose

Stroke count: 38

Though the word bara (rose) is well-known, the kanji is so complicated that most Japanese people use it in kana (バラ) or with furigana. The characters 薔 and 薇 both involve the 艸 (grass/plant) radical and many strokes. You’ll still see the kanji in fancy menus, botanical texts, or poetry.

5. 橄欖 (Kanran)

Meaning: Olive

Strokes: 34

While this word refers to olives, it’s mostly used in Chinese or academic contexts. Japanese more commonly uses the katakana form オリーブ. But you might see this in scientific texts or ingredient labels.

6. 紅鶴 (Koukaku)

Meaning: Flamingo

Strokes: 30

紅 means red or crimson, and 鶴 means crane. While each kanji is readable on its own, 鶴 is not commonly encountered in everyday writing. The compound 紅鶴 (こうかく) literally means “red crane,” but it’s used poetically to refer to a flamingo.

You might come across this term in zoos, nature books, or literary works, where it’s used as a majestic or symbolic expression.

7. 馬鹿 (Baka)

Meaning: Fool, Idiot

Strokes: 21

You’ve probably heard baka before, one of the most common Japanese insults out there. It means “fool” or “idiot,” and while it’s usually written in hiragana (ばか) or katakana (バカ), the kanji version consists of two animals: horse (馬) and deer (鹿).

So what do a horse and a deer have to do with being an idiot? Some say it comes from an old story about mistaking a deer for a horse, like a metaphor for blind obedience or just plain foolishness.

Either way, its kanji form feels kind of stiff or old-school. Most people stick with kana when writing it, unless they’re going for a dramatic or literary vibe.

Start taking Japanese lessons and master kanji skills with us!

The great news is that nowadays, you’re more likely to read kanji than write them by hand. That said, we still recommend practicing your kanji strokes.

If you love learning Japanese and want to master kanji, consider starting at top language schools like Coto Academy. At Coto, you’ll gradually ease into both the Japanese language and culture, learning real Japanese as it’s spoken in everyday life.

We offer both part-time and intensive courses across four campuses in Tokyo and Yokohama. Not in Japan? No problem! We have interactive online lessons so you can learn Japanese wherever you are.

What sets us apart is our personalized approach: classes are small, with only 8 students per classroom, so you get plenty of speaking practice and individual attention.

Interested? Fill out the form below for a free level check! You can also schedule a free consultation or chat with our team to find the best learning path for you.

FAQ

What is the hardest kanji in Japanese?

たいと(taito) is the most difficult Japanese Kanji on record, with a total of 84 strokes. It is formed by combining 3 雲 (くもkumo) with 3 龍 (りゅうRyuu). 雲 means cloud and 龍 means dragon in English. たいと is said to be a type of Japanese surname. Although this kanji is recorded in the <Rare Surname Dictionary>, its true existence is still unverifiable.

Where does kanji characters come from?

Originating from China, kanji takes a significant part in the Japanese language. It is widely used in the daily life of the Japanese people.

How many kanji characters do you need to know?

Usually, a person who grows up speaking Japanese knows about 3500 to 4000 kanji.

Love reading our blog? You might be interested in: