Similar to the language, how Japanese people celebrate New Year is different — although not entirely. There’s the usual fireworks, close-knit dinners and snuggles. But heavy in culture and hundreds of years of tradition, you’ll find families and friends making their first shrine visit of the year, buying lucky bags called fukubukuro and sending New Year’s postcards called nengajo.

Unlike China and Korea, which still follow the old lunar calendar, Japan sets the new year according to the modern calendar. The celebration is considered to be a more important event than Christmas and as such, many companies and public facilities have about a week-long holiday from the end of the year to around January 1 to January 3. Here, we’re taking you seven ways people celebrate New Year in Japan.

Planning to spend the 2022 New Year at home? We’ve got the right expression for you: 寝正月 (neshougatsu), which translates to “sleeping New Year”.

Oosoji (大掃除): A Very Big Cleaning

To prepare and welcome the new year, Japanese people clean up their homes and offices. The word literally means “big cleaning”, and the practice symbolizes making way to a fresh start. Of course, how people interpret the term “cleaning” is up to them. For the most part, it’s top-to-bottom cleaning, which is another word for scrubbing, sweeping and mopping the house until it’s spotless.

Japanese people will also donate old things and replace them with newer ones. Oosoji is usually done near New Year’s Eve.

Osechi Ryouri (おせち料理) Preparations

The osechi ryouri is the name for a specialty dish the Japanese eat to celebrate the New Year. Osechi closely resembles your everyday bento, and it is served stacked in three to four tiers. The dishes included will vary depending on the region.

When it started off during the Heian period as an offering to the gods, the food was kept relatively simple — boiled vegetables in soy sauce and vinegar. Over time, the lineup turned more elaborate and expensive. Now, each selection has special associations. The Japanese bitter orange, for example, symbolizes a wish for children, while konbu signifies joy as it sounds similar to the Japanese word for it (yorokobu).

Originally, most people would spend two or three days cooking the dishes at home. Nowadays, it’s not uncommon for Japanese to order them from supermarkets and fancy shops.

Oomisoka (大みそか)

One custom, originated from the Edo era, consists of eating soba on New Year’s Eve. The long thin noodles represent long life. These noodles are also easy to cut, which represents cutting away the bad luck of the previous year.

Check out our other blog posts on Japanese New Year:

- How to Say “Happy New Year!” in Japanese

- What’s A Japanese New Year Postcard, Nengajo?

- Getting to Know Japanese New Year Culture

- Fun Facts About Japanese New Year Traditional Dish: Osechi Ryouri (おせち料理)

- New Year’s Day: A Time of Tradition

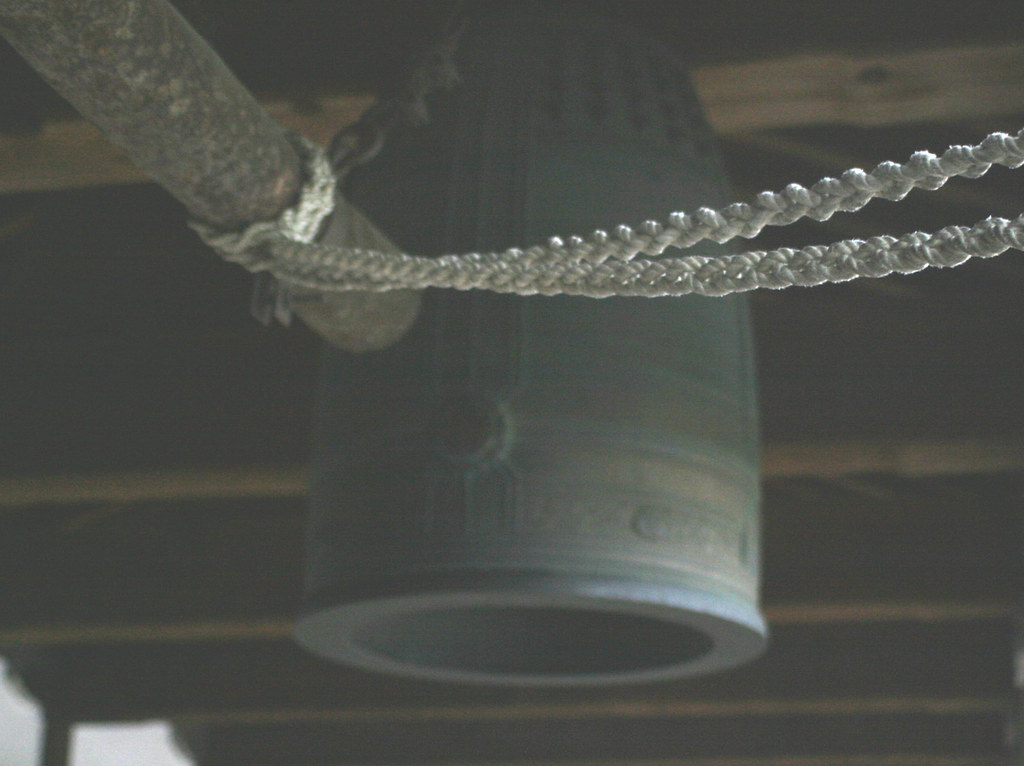

Joya no Kane (除夜の鐘): New Year’s Eve Bells

On New Year’s Eve, around 11pm, Buddhist temples all over Japan will ring the bells for a total of 108 times. This represents the removal of the 108 worldly desires. When the last struck is done, you’ll be cleansed of your problems from last year.

When the bell is finally struck for the 108th time, it is believed that you’ll be cleansed of your problems and worries from last year. Some temples allow visitors to ring the bell, although this might be subject to additional fee and ticket purchases. If you live in Tokyo, head to the Sensoji Temple in Asakusa orZenpukuji Temple in Azabu-juban to be mesmerized by this tradition.

Ganjitsu (元日): First Day of January

On the first morning of the year, Japanese families eat rice cake soup and the osechi dishes they’ve prepared (or ordered). The New Year wishes cards posted from November to the end of December called nengajou (年賀状) will be distributed to all homes.

Hatsumode (初詣): First Shrine Visit

Another custom is the first visit to a shrine or temple. People pray for safety and peace over the coming year. The most famous temples in Japan are terribly crowded and it’s not rare to wait for a few hours before being able to pray. Each year, about 2,5 to 3 millions visitors will come to pray in the Meiji shrine and in the famous Asakusa Sensouji temple.

A popular way to welcome the New Year is for families to watch the first sunrise of the New Year (はつひので or hatsuhinode). Typically, they can also make the first temple or shrine visit of the year (hatsumode) on the same day, too.

Fukubukuro (福袋): Lucky Bag

True to its name (“fuku” meaning luck and “fukuro” meaning bag), it all comes down to intuition when it comes to this Japanese New Year custom. Merchants will fill the lucky bag with random contents and sell them at a great discount — sometimes for half the original price — and, without having any idea what’s inside it, you’ll buy them.

Price ranges from 10,000 to 100,000. Although it seems pricey, remember that the value of the lucky bag’s goods is often worth twice as much. In fact, in electronic stores, you’ll find customers waiting in line to get their hands on one of them.

In Japan, the lucky bags are a serious institution and you’ll get real bargains. If you cannot chose brands, you’ll still get at least an idea of what could be inside. Prices range from 10,000 yens to 100,000 if you’re tempting your luck in an electronic store! The value of the lucky bag’s goods is often worth twice as much. Many customers will wait in mine to get their hands on a lucky bag.