Seventeen syllables. Three lines. A single moment captured forever. Haiku is the most iconic form of Japanese poetry, and the most deceptively simple. With only a few carefully chosen words, a haiku depicts nature, emotion, and the human experience into a well-rounded poetic snapshot. Even with its shortness, the haiku carries a deep cultural weight in Japan.

But can anyone write haiku? Or is it reserved only for specific Japanese poets? In this article, we will explore what makes a haiku so unique, from its structure and style to its rich history. We will also display some of the most famous Japanese haiku ever written so that by the end, you might even feel inspired to write one yourself!

What is a haiku?

Haiku is a traditional Japanese poem with three lines and seventeen syllables. But these short verses carry surprising depth. A haiku is all about capturing a moment– something you see, feel, or hear that makes you stop and notice the details of the world around you.

Traditionally, a haiku follows a 5-7-5 syllable pattern. This pattern is five syllables in the first line, seven in the second, and five again in the third. In Japanese, the structure is based on sounds called on. They do not line up exactly with English syllables, but the general rhythm is quite similar.

What makes haiku different from other poetry?

Haiku poems emphasize simplicity, intensity, and directness of expression. A haiku poem usually represents a single and concentrated image or emotion. Because of their structure, brevity, and syllabic pattern, these poems are generally allusive and suggestive, encouraging the reader to interpret the significance of the words and phrases used. Thanks to their shortness and simplicity, readers can often easily remember verses, which has helped to propagate the genre across the globe.

Traditional haiku often focuses on nature, the seasons, or small, everyday scenes that otherwise go unnoticed. There is usually a sense of stillness or reflection, the Japanese call it “satori”, meaning a little flash of insight or awareness.

You might also come across another term: kigo, or seasonal words. In classic haiku, each poem includes a word or phrase that links it to a period of the year.

Common haiku themes are related to nature, changing seasons, mindfulness, simplicity, and impermanence. This makes sense: Japanese poetry in general is heavily influenced by Zen Buddhism, which places importance on living in the present moment. Japanese haiku poems are often philosophical in nature, focusing on small, everyday moments.

At the end of the day, writing or even just reading a haiku is an exercise of being present. It is a way of noticing the beauty in everyday life.

The origin of haiku

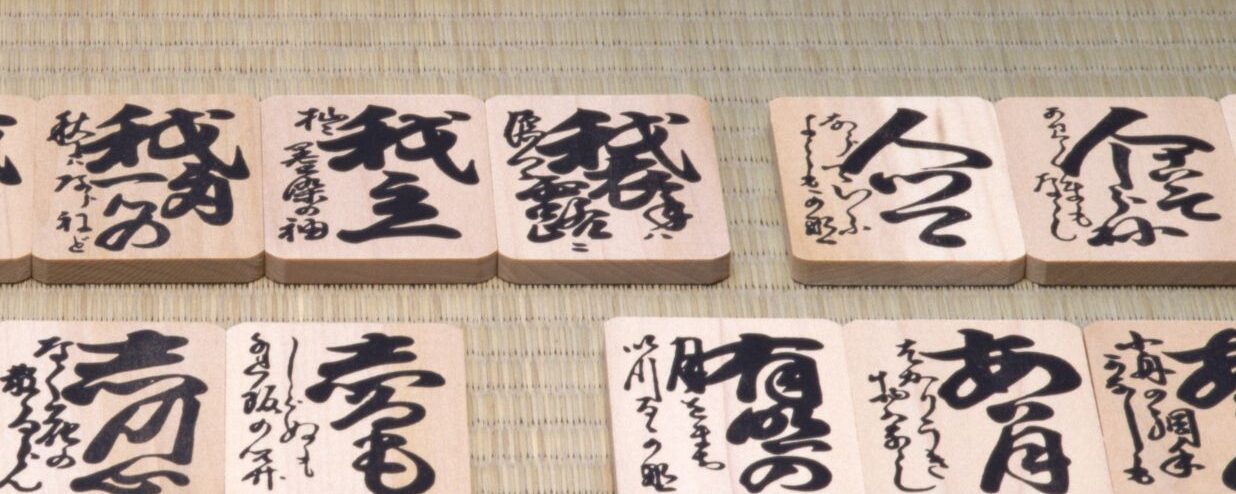

To find the first trace of poetry in Japan, we have to go back to the 9th century in Japan. Haiku began as the opening line of a longer collaborative poem called renga. In the 1300s and 1400s, poets would get together and take turns writing linked verses. The very first stanza, called a hokku, was meant to set the mood: it was often something light, seasonal, or playful.

Over time, hokku verses began to evolve to take life on their own. A group of four poets, known as the “haiku masters,” began focusing more on the hokku itself as a standalone poem and experimenting with different styles and themes. These verses began to be appreciated for their own worth and became distinct as a poetic form, popularized by poets such as Matsuo Basho (1644–1694) and Yosa Buson (1716–1783).

Basho, called by some the father of haiku, was known for using imagery and metaphors that evoked a sense of the natural world. Basho’s poems were also known for their strict syllable count and lack of rhyme, which added to the poems’ sense of simplicity and elegance.

古い池 や蛙飛びこむ⽔の⾳

Furu ike ya kawazu tobikomumizu no oto.

The old pond!

A frog jumps in—

the sound of water

By Matsuo Basho

This poem by Basho, presumably written sometime in the 1680s, paints a vivid picture of an old pond and the sound of a frog jumping in, and is one of the most famous haiku ever written.

Basho, Buson, Kobayashi, and Masaoka Shiki (1867–1902), the four haiku masters, helped popularize the genre during the 18th and 19th centuries when many amateur and professional poets began to write haiku. It also began to be used in other art forms, such as painting and woodblock printing.

Here are some popular poems by Shiki, Buson, and Kobayashi, each of them dedicated to a different season.

酔って寝て夢で泣いていた⼭桜

Yotte nete yume de naiteita yamazakura.

I got drunk, a sleep.

And wept on the dream.

A wild cherry blossoms.

Spiring haiku, by Masaoka Shiki.

菜の花や/⽉は東に⽇は⻄に

Na-no-hana ya tsuki ha higashi ni hi wa nishi ni

The canola flowers.

The moon in the east.

The sun in the west.

Summer haiku, by Yosa Buson

⽜の⼦が/ 旅に⽴つなり/秋の⾬

Ushi no ko ga tabi ni tatsu nari aki no ame

The baby cow

Goes on a trip.

The autumn rain.

Autumn haiku, by Kobayashi Issa

At the end of the 19th century, hokku was renamed haiku by Shiki. Haiku began to appear in Western literature, and in 1905, Paul-Louis Couchoud became one of the first European translators of the form, converting many short Japanese verses into French. Writers such as Jack Kerouac and members of the Beat Generation fell in love with its minimalism qualities and started to adopt them. Today, haiku is applied retrospectively to all hokku verses written in the past.

The genre then spread to other countries worldwide, particularly in the 20th century, as many poets and writers worldwide began to write and adapt the form to their own cultures and styles. Haiku societies and organizations were formed, and contests and journals were established. Though the genre originated in Japan, it later also became a significant element of English poetry, as it influenced the Imagist movement in the early twentieth century.

How to write a haiku: Rules and structure

Writing a haiku might look effortless, but there is actually a lot of intention behind those three little lines. Traditional Japanese haiku follow some clear rules, but like all art, those rules can also be bent and changed. Here’s a simple guide:

1. The Classic 5-7-5

The most well-known rule of haiku is its syllable pattern:

- 5 syllables in the first line

- 7 syllables in the second

- 5 syllables in the third.

In Japanese, this structure is based on on, which are short phonetic sounds that are not exactly the same as English syllables. That is why Japanese haiku often feel shorter when translated into English. Still, many English-language haiku stick to the 5-7-5 pattern as a way of honoring traditions.

Example:

Morning chill sets in

Leaves fall without a warning

Autumn sighs again.

It is short, vivid, and emotional all in only 17 syllables.

2. Includes kigo: Seasonal word

Traditional haiku almost always include a kigo, or seasonal word. This could be something obvious, like Sakura (cherry blossoms) for spring or yuki (snow) for winter, or something more subtle, like a type of insect or flower that only appears during a certain time of year. The kigo anchors the poem in time and connects it to the natural world. Japanese haiku poets often use kigo dictionaries to find just the right seasonal phrase.

3. Kireji: Cutting word

Another unique element in Japanese haiku is the kireji, or “cutting word.” It does not translate directly into English, but it adds a kind of pause, emphasis, or emotional tone. Think of it like a poetic comma, dash, or exclamation mark. In Bashō’s famous frog haiku, ya is the kireji:

Furu ike ya – “An old pond —”

It creates a break between images, letting the reader sit with the moment before moving on. In English haiku, writers often use punctuation or a line break to create a similar effect.

Traditional vs. Modern Haiku

Traditional haiku usually follow all the rules: 5-7-5 structure, seasonal reference, kireji, and a strong focus on nature.

Modern haiku, on the other hand, tend to be more flexible. Some poets ditch the syllable count altogether and focus instead on mood or imagery. Others write haiku about urban life, social issues, or even digital culture, which is a more modern take on haiku.

Here is a modern example that breaks the 5-7-5 rule:

Texting in the rain

I pause mid-thought to listen

to nothing at all.

Still feels like a haiku, right?

Styles and language of haiku

Haiku is not flashy language or complex storytelling. It is about getting straight to the heart of a moment with as few words as possible. That is what makes the style and language of haiku so unique and powerful.

1. Simplicity is key

The beauty of a haiku often comes from its simplicity. Haiku poets choose their words carefully because every syllable counts. There is no room for fluff, and that is kind of the point. A good haiku strips things down to what really matters. But simple does not necessarily mean boring. The best haiku uses simple, ordinary words to describe immensely extraordinary feelings.

2. Show, Don’t Tell

Haiku rarely explain. Instead, they show. They invite you to experience a moment for yourself through clear, sensory images. Think of it like a photograph in words.

First snowfall whispers

over rooftops and bare trees

no one says a word.

From this haiku, you can feel the cold. Maybe even remember a moment just like it.

3. Emotion without drama

Unlike other forms of poetry that wear emotion on their sleeve, haiku prefers emotional subtlety. It does not shout. And yet, it can leave an impression. This quiet emotional power is part of what makes haiku so moving. You might read one and not even realize it hit you until a few minutes later.

English vs. Japanese Haiku

Haiku written in English are a little different from the original Japanese versions. In Japanese, haiku is written in a single vertical line with natural breaks built into the language. The rhythm is based on on, not syllables, so translations are often shorter than their English counterparts.

English haiku usually:

- Use three horizontal lines.

- Follow a 5-7-5 syllable count (but not always)

- Skip the kireji (cutting word) or use punctuation instead.

- Include nature, but not necessarily a seasonal reference

10 Famous Haiku Poems by Japanese Poets

Haiku poems are known for their ability to paint a vivid picture in just a few words. Their minimal nature forces writers to only include the essentials — making each word count. Here are 10 well-known haiku written by Japanese poets and translated into English.

1. The Frog Haiku by Matsuo Basho

Japanese:

古池や

蛙飛びこむ

水の音

Romaji:

Furu ike ya

kawazu tobikomu

mizu no oto

English:

An old pond—

a frog jumps in,

the sound of water.

Let’s start with the most iconic haiku of all time. Written by Matsuo Basho, this poem is deceptively simple. It is not just about a frog, it is about stillness, awareness, and that one small action that breaks the silence. If you only ever remember one haiku, it will probably be this one.

2. “Moon and Flowers” by Yosa Buson

Japanese:

菜の花や

月は東に

日は西に

Romaji:

Na no hana ya

tsuki wa higashi ni

hi wa nishi ni

English:

Canola flowers

the moon in the east,

The sun in the west.

Yosa Buson was a painter as well as a poet, and you can really feel that in his work. This haiku paints a perfect visual scene; you can almost see the soft yellow of the flowers and the glowing sky, balanced between day and night.

3. “Life Is Fleeting” by Kobayashi Issa

Japanese:

やせ蛙

負けるな一茶

是にあり

Romaji:

Yase kaeru

makeru na Issa

kore ni ari

English:

Skinny frog,

don’t give up! Issa’s

here to cheer you on.

Issa is known for his empathy, especially toward the small and overlooked. His haiku are often humorous and emotional, much like this one. You can feel the poet rooting for a scrappy little frog (and maybe, in a way, for himself too).

4. “The Bite of Reality” by Masaoka Shiki

Japanese:

柿くへば

鐘が鳴るなり

法隆寺

Romaji:

Kaki kueba

kane ga narunari

Houryuuji

English:

Biting into a persimmon

a temple bell rings

at Horyuji.

Masaoka Shiki was a haiku reformer who brought new life to the genre in the late 1800s. This poem captures a specific moment, taking a bite of fruit, hearing the bell, and suddenly being transported into a calm, reflective state.

5. “Morning Glory” by Chiyo-ni

Japanese:

朝顔や

つるべ取られて

もらい水

Romaji:

Asagao ya

tsurube torarete

morai mizu

English:

Morning glories

I give up my well bucket,

ask my neighbor for water.

One of the most famous female haiku poets, Chiyo-ni captures the beauty of flowers, so lovely she does not want to disturb them, even if it means borrowing water.

6. “Lighting One Candle” by Yosa Buson

Japanese:

ろうそくの火

次のろうそくへと

春の夕暮れ

Romaji:

Rosoku no hi

Tsugi no rousoku e to

Haru no yuugure

English:

The light of a candle,

Is transferred to another candle–

Spring twilight

7. “A World of Dew” by Kobayashi Issa

Japanese:

露の世や

露のひとつに

戦いの世

Romaji:

Tsuyu no yo ya

Tsuyu no hitotsu n

Tatakai no yo

English:

A world of dew,

And within every dewdrop,

A world of struggle.

8. “Cricket” by Kobayashi Issa

Japanese:

聞いてごらん

台所のひさしに

鈴虫の声

Romaji:

Kiite goran

Daidokoro no hisashi ni

Suzumushi no koe

English:

Listen! A cricket

Chirps under the kitchen’s

Eaves: my lonely home

9. “ A Poppy Blooms” by Katsushika Hokusai

Japanese:

書いては消し

また書いては消す

ひとつのけし

Romaji:

Kaite wa keshi

Mata kaite wa kesu

Hitotsu no keshi

English:

I write, erase, rewrite

Erase again, and then

A poppy blooms.

A poppy blooms is a haiku that reflects on the thoughtfulness that goes behind every written piece. It emphasizes on the reflection that a writer needs to hold in order to create a piece of work that is representative of their ideas and creativity.

10. “Winter Moon” by Yosa Buson

Japanese:

ろうそくの火

次のろうそくへ

春のたそがれ

Romaji:

Rousoku no hi

Tsugi no rousoku e

Haru no tasogare

English:

The light of a candle

Is transferred to another candle—

Spring twilight

| Term | Japanese | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Kigo | 季語 | A word or phrase that indicates the season. |

| Kireji | 切れ字 | A “cutting word” used to separate phrases or ideas in a haiku. |

| Ashi | ⾜ | The number of syllables in a line. |

| Yuugen | 幽⽞ | A feeling of mystery or depth in a haiku. |

| Sabi | 寂 | A sense of loneliness or quietness in a haiku. |

| Wabi | 侘 | A feeling of simplicity or humble beauty in a haiku. |

| Shiori | しおり | An index of the kigo used in a haiku collection. |

| Kansou | 感想 | The expression of emotions or feelings. |

| Makura | 枕 | The use of a preface or introduction in a haiku. |

| Ma | 間 | The use of negative space or “empty” elements in the poem. |

| Shasei | 写⽣ | The use of direct observation in writing a haiku. |

| Shasei-ga | 写⽣画 | A painting or sketch made as part of the writing process. |

Where to learn haiku

To learn more about haiku, there are several books and online resources about this form of poetry. To start, “Haiku: The Complete Collection” by Matsuo Basho is a compilation of all the known verses written by Basho. The book also gives insight into his life and poetic vision.

Another valid book is “The Classic Tradition of Haiku: An Anthology” by Faubion Bowers. The work is a comprehensive collection of haiku from traditional Japanese masters such as Basho, Buson, and Issa, as well as other contemporary poets. The publication includes Japanese texts and English translations, as well as a historical and cultural context for each poem.

Finally, if you also want to start writing, “The Haiku Handbook: How to Write, Share, and Teach Haiku” by William J. Higginson offers valuable lessons to start writing, sharing, and teaching the poem, with tips and exercises that help readers understand the form and improve their writings. This work covers the traditional rules and structures of haiku, but also provides an overview of how it has evolved and how it is written today.

Online resources to enjoy haiku

Masterpiece of Japanese Culture is an extensive online library of haiku poems and other genres divided by genre and author. Similarly, ModernHaiku.org is an online journal that publishes poetry and essays on haiku from around the world, with a focus on contemporary ones.

The Haiku Foundation is a non-profit organization that provides a wide range of resources for haiku poets and enthusiasts. The platform has an extensive online library of the poem, as well as a blog, a podcast, and a series of educational videos.

If you want to be in the community, the Haiku Society of America is a national organization for poets and enthusiasts in the United States. The organization publishes an online journal called the “Frogpond Journal” with poetry and essays about it. World Haiku Association is an online community where poets can share their work and receive feedback from other poets.

Finally, Haiku News by the Mainichi is an online platform that publishes haiku poetry and essays from around the world.

mainstream on social media platforms, as many online users have been sharing original poems on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook.

Conclusion

At first glance, a haiku might seem small, with just a few lines and a handful of words. But in those brief moments, a haiku can transport you, stir up emotion, or help you notice something you might have otherwise missed. That is the magic of this centuries-old Japanese poem: it turns ordinary moments into something truly unforgettable.

If you are learning Japanese or exploring Japanese culture, writing haiku is a simple but powerful way to connect more deeply. And if you need help getting started, Coto Academy offers resources, language lessons, and cultural tips that can guide you along the way.

Check out our Japanese online classes or part-time Japanese classes, or fill out our contact form for a free level check and consultation!

FAQ

What is a haiku?

Haiku are short unrhymed poems composed of only three lines and seventeen syllables

What are the rules for structuring a haiku?

- There are no more than 17 syllables.

- It is composed of only 3 lines.

- Every first line has 5 syllables, the second line has 7 syllables, and the third has 5 syllables.

Who are the famous haiku poets in Japan?

Matsuo Basho, Yosa Buson, Kobayashi Issa and Masaoka Shiki are known to be haiku masters.

How many syllables are in a haiku?

Traditionally, haiku use 17 phonetic “on” in Japanese. English versions often follow the same syllable count, though modern poets may experiment.

What is kigo in haiku?

A kigo is a seasonal word or phrase, like “snow” or “cherry blossoms,” that roots the poem in a specific time of year. It is a key feature in classical haiku

Can you write haiku in English?

Like what you read? You might be interested in: