Ever wondered why it takes longer for you, a native English speaker, to learn Japanese compared to your other foreign friends? In our previous article, we discussed how while Japanese is already a challenging language to learn, it’s even more difficult if you grow up speaking English. Why is that?

The answer lies in the vast differences between the English and Japanese languages. From the writing systems and grammar structures to the contextual basis of communication, there are a few similarities that can speed up the learning process. Unlike Chinese and Korean speakers, who can draw upon some similarities in their own language, English speakers face additional hurdles. In this article, we’ll explore the reasons why Japanese is more difficult for English speakers to learn and provide insights on how to navigate these challenges!

Are there any similarities between English and Japanese?

While the differences between English and Japanese outweigh the similarities, there are some non-obvious traits that both language share. Hopefully, these similarities give you a piece of mind when you start learning Japanese.

Japanese and English languages borrow words from each other

Loan words in Japanese, or gairaigo (外来語), are words borrowed from foreign countries other than China. While there are some loanwords that come from Europe like Dutch and Portuguese — but most of them come from English. In fact, 10% of the vocabulary of modern Japanese comes from English.

For example, besides arigatou gozaimasu, a lot of friends would say a Japan-ized “thank you” to each other casually. The Japanese alphabet doesn’t recognize the consonant “th, so instead,the “s” is used.

サンキュー

Sankyuu.

Thank you.

Nowadays, a lot of Japanese people tend to prefer using English loanwords over their Japanese equivalents. Some people might even have a hard time identifying the pure Japanese word because they’re so used to using its loanword equivalent! For example:

| English | Loanword | Japanese |

| Copy machine | コピー機 (kopiiki) | 写真機 (shashinki) |

| Knife | ナイフ (naifu) | 包丁 (houchou) |

| Table | テーブル (teeburu) | 机 (tsukue) |

| Hotel | ホテル (hoteru) | 客舎 (kyakusha) |

Likewise, while the Japanese language has borrowed a lot of English words, we can say the same thing the other way around. Let’s take tsunamis, for instance. There’s no English word to describe huge tidal waves, so it was borrowed from the Japanese. Other examples include sushi, katsu, skosh (as in “just a skosh”) and tycoon. Read more loanwords that come from Japanese here!

Japanese and English Languages Start with a Subject

This is a fundamental aspect of both Japanese and English. In English, we know that the subject of a sentence will always come first, followed by a verb, and then the object — this is the simplest grammar structure.

For example, in the word, “The dog is playing a ball”, “the dog” is the subject”, “is playing” is the verb, and “the ball” is the object.

While Japanese has a different structure (more of that later!), the subject is usually placed at the beginning of the sentence. Simple, right? Take a look at the sentence below.

私は犬を愛しています。

Watashi wa inu o aishite imasu.

I love dogs.

Here, “Watashi” is the subject, “neko” is the object, and “aishiteimasu” is the verb.

Although there are some exceptions to these rules in both languages, such as in questions or certain types of emphasis, the general tendency is for sentences to follow this structure.

Like Japanese, English Has Honorifics

If you have heard -kun (くん), -chan (ちゃん), -san (さん), and -sama (さま) before, then you know that in Japan, you just simply do not call people by their names. To address someone or speak about someone, you need to use honorifics — a suffix that goes after the person’s name. For example:

佐藤さん

Satou san

田中様

Tanaka sama (sama indicates more respect)

English also has its own list of honorifics, like Mr., Mrs., and Ms. They’re used to address people politely, and in formal situations. The only difference is that Japanese honorifics can also be used to address someone younger or socially lower than you — such as -kun (くん), used on friendly terms for male friends, and chan, used for children. Another thing is that English doesn’t use honorifics as regularly as Japanese. In fact, you won’t find someone calling you Mister or Miss on a casual meeting.

Differences Between Japanese and English

Different Writing Systems

While the English language only has 26 letters based on the Latin alphabet, the Japanese has not one, not two, but three writing systems. The first two, katakana and hiragana, are phonetic systems that share the same sounds. Katakana is usually used for foreign words while hiragana is used for everything else including particles.

Hiragana and katakana are similar to the alphabet; these characters represent a syllable that when combined with other characters, makes up a Japanese word.

The trickiest part that most foreigners have a hard time with is kanji — the third writing system in the Japanese language. Unlike hiragana and katakana, a kanji must be memorized separately as one character does not represent one “sound”, but one “meaning”. In other words, kanji are closer to ideograms that represent words and concepts instead of a writing system.

This is why there are thousands of kanjis there are thousands of them — approximately 4,400 kanji characters. Just as a reference, to pass JLPT N3, you’ll need to learn 650 kanji.

Japanese has a different sentence structure

I want a cat. I read a book. You are drinking a cup of coffee. The English language follows the basic grammar pattern that we all use unconsciously: the subject-verb-object (SVO) pattern.

In Japanese, the basic sentence structure follows a subject-object-verb (SOV) pattern. For example:

| 私 Watashi | は wa | 寿司 sushi | を食べます o tabemasu |

| Subject | Object | Verb |

On the other hand, it will look like this in English.

| I | am eating | sushi |

| Subject | Verb | Object |

This means when you’re deciphering a Japanese sentence too literally, the translation can go awry. Take a look at another example below.

| Subject | Subject Particle | Location | Location particle | Object | Object Particle | Verb |

| 田中さん | は | 喫茶店 | で | コーヒー | を | 飲んでいます。 |

| Tanaka-san | wa | kissaten | de | koohii | o | nondeimasu |

| Tanaka | cafe | at | coffee | is drinking |

Doesn’t make sense, right? If you’re used to speaking in a language that adopts the basic SVO pattern, you might need some time before getting used to the Japanese sentence pattern.

The Japanese Language Likes to Omit Subjects

As you learn to speak Japanese in real situations or listen to conversations, you might notice that a lot of Japanese people like to omit subjects, especially when it indicates the first person.

In English, removing a subject from a sentence is grammatically incorrect. You can’t just say “want eat” to someone, as this is technically an incomplete sentence. Who wants to eat?

In Japanese, however, when the subject is obvious and heavily implied in the context of the conversation, a sentence would not require one. For example, imagine a scenario where you just got home from the convenience store. Your mom was there waiting for you at the entrance, and she asks:

Mom

何を買ったの?

Nani o katta no?

What did (you) buy?

You

ファミチキを買った。

Famichiki okatta.

(I) bought a Famichiki.

Noticed how even the mom omits “you” in her question? The right sentence would be, あなたが何を買ったの (anata ga nani o katta no). However, when spoken, it will sound unnatural because, at this point, we know that your mom is directly asking a question to you.

The same goes for your answer. You can say, 私はファミチキを買った (watashi wa famichiki o katta), but it’s clear that you’re referring to yourself.

Another example will be when you are feeling a headache. In English, this will simply be, “I have a headache.”

In Japanese, the literal translation will be

私は頭がいたい。

Watashi wa atama ga itai.

However, as you study more advanced Japanese, you realize that “ha” is used to put emphasis on the subject. Therefore, when you say, “私は頭がいたい,” you are claiming, “I am having a headache.”

Of course, the meaning doesn’t change, and it’s not dramatically incorrect. However, it’ll affect. the overall nuance of your statement.

Keep in mind that the use of subject omission in the Japanese language is a complex cultural and linguistic phenomenon that has developed over time due to various social and linguistic factors. Japanese is a language that places a high value on brevity and efficiency in communication, and omitting the subject can help to make sentences shorter and more concise. If a sentence contains a lot of obvious possessive determinators and subjects, we can clean it up. For example:

私は私のカバンを忘れてしまいました。

Watashi wa watashi no kaban o wasurete shimaimashita.

I lost my bag.

Here, if you are declaring that you are losing your own bag, you can simply say:

カバンを忘れてしまいました。

Kaban o wasurete shimaimashita.

(I) lost (my) bag.

There are also other ways in which the Japanese language can help indicate if someone is performing the action for someone else — without explicitly mentioning the subjects. These are done through conjugations like 〜てあげる, 〜てくれる, and 〜てもら. If you want to read more about that, head here.

The Japanese language has different levels of formality

English has its own system of formal language, but it’s generally less complex than Japanese. To put it into perspective, English ‘formal’ language relies more on vocabulary and syntax rather than specific verb forms and grammar rules.

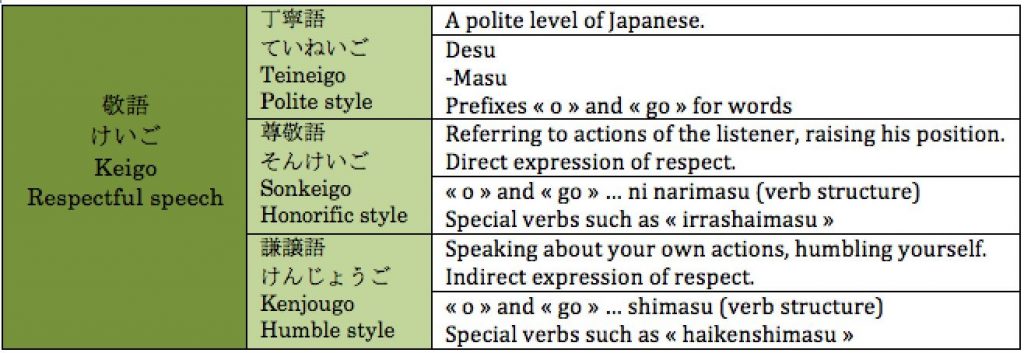

In the Japanese language, there is a special way of speaking called keigo which is used to show respect to people of higher social status. There are three main levels of keigo: sonkeigo (respectful language), kenjougo (humble language), and teineigo (polite language). Each keigo with its own set of verb forms, vocabulary, and grammar rules.

Which level of keigo to use depends on the relationship between the speaker and the listener. For example, if you are talking to your boss, you should use sonkeigo (尊敬語) to show the utmost respect.

On the other hand, when talking to a client, your boss becomes part of your in-group or uchi (内), and the client is perceived to be of higher social status. In this case, you would use kenjougo (謙譲語) to show humility towards the client. Complicated, right?

In essence, keigo is used to show respect and maintain social harmony, but it can be hard to navigate as it depends on various social hierarchies and relationships.

English has more vowels than Japanese

Despite its intricate writing system, we can bet that Japanese is more simple in one thing: its pronunciation. The Japanese language has significantly fewer vowels sounds than English.

Japanese has only five vowel sounds: /a/, /i/, /u/, /e/, and /o/ (あ, い, う, え, and お). These sounds are more consistent than in English because they are pronounced based on how they are written. For example, the word haha (母) is pronounced as it is: ha-ha.

This isn’t necessarily true for English. English has fifteen vowel sounds represented by the letters a, e, i, o, and u. This means that even when a word has the same vowel, it can be pronounced differently. For example, words like “able” (ay-ble) or “salt” are pronounced differently, even when it contains the vowel “a”.

Different Pronunciation

Now that we’ve gotten over the vowels, we can dive into how Japanese pronunciation differs from English. Japanese uses double consonants and long vowels more than English, which can be a bit of a tricky gap to overcome if you speak English all the time.

For example, the grandpa and uncle are pronounced almost similar if not for the fact that grandpa, or ojii–san, in Japanese, has a long vowel.

おじいさん

Oji-i-san

Grandfather

おじさん

Oji-san

Uncle

This is another tricky part that foreigners have trouble with. English also has more consonant sounds in Japanese; 24 compared to 14 consonants. While this makes it seem like Japanese people will have a harder time learning English, native English speakers have found it tricky to nail pronouncing “R” in Japanese. The “r” in Japanese sounds like a middle point between the English “r” and “l”.

Japanese is a highly contextual language compared to English

お疲れ様です (otsukare sama desu). よろしく音がいします (yoroshiku onegaishimasu). We all have probably learned these basic phrases and started using the regularly. Intepreting their nuance and meaning, however, is another thing.

Both otsukare sama desu and yoroshiku onegaishimasu are one of the many phrases with multiple meanings. This is because Japanese is considered a high-context language. This means that in Japanese, a lot of meaning is conveyed through context, nonverbal cues, and implicit communication. What does this mean?

In Japanese, it’s common to use vague language and rely on context to convey the intended meaning. For example, if you’re asking someone on a date tomorrow, they might say:

明日は厳しいけど…

Ashita wa kibishii kedo…

Tomorrow is (a bit hard).

Here, we might be inclined to press further: what about the next day? Or the weekend? This is where you will need to read between the lines and realize that that person is indirectly saying no.

On the other hand, Englsih is a more direct language, and meaning is often conveyed through explicit and precise language. Nonverbal cues are less relied upon than in Japanese. English sentences usually include the subject and verb, and context is less important for understanding the meaning of a sentence.

Let’s Learn Japanese with Coto Academy!

Overall, there are a lot of differences between Japanese and English that can make studying the language hard. If you’d like to study Japanese with professional teachers, why not join Coto Academy? We have a range of courses ranging from beginner crash courses to business Japanese!

We also have an online lesson portal, where you can easily browse lessons and book a class.

If you’re ready to get started, fill out the inquiry form below for a free level check and course consultation!